File - Gabrielle Olson

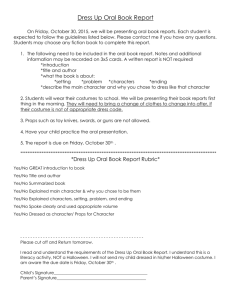

advertisement

EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME FROM THE 17TH CENTURY TO THE 18TH CENTURY Gabrielle Olson ADM 561 November 7, 2012 San Francisco State University Abstract 1 EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 2 The purpose of this paper is to describe the major changes and the evolution of women’s fashion garments in the seventeenth and eighteenth century of the aristocracy. This paper strictly discussed the clothes women wore. France and the effects of French fashion on England was the main focus. As well as the effects of English fashion in France in the late eighteenth century. Major garment and silhouette changes of the centuries are described. Historical events are used to correlate with the causes of fashions of the time. How fashions spread and the influences of certain trends are also discussed. Table of Contents EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 3 Abstract...........................................................................................................................................2 Chapter I. Introduction..................................................................................................................4 Purpose...........................................................................................................................4 II. 1600-1700: The Seventeenth Century.........................................................................5 Women’s Dress.............................................................................................................5 Mid Seventeenth Century................................................................................5 Late Seventeenth Century...............................................................................6 Conclusion....................................................................................................................7 III. 1700-1750: The Early Eighteenth Century..............................................................8 Historical Background.................................................................................................8 Women’s Dress............................................................................................................9 Sacque Gown.................................................................................................9 Figure 3.1..............................................................................................9 Robe à la Française......................................................................................10 Figure 3.3............................................................................................10 IV. 1750-1800: The Late Eighteenth Century....................................................................11 Women’s Dress.........................................................................................................11 Fashion Plates............................................................................................12 French Revolution, the end of the Eighteenth Century..............................12 Figure 4.1...........................................................................................12 Conclusion..............................................................................................................12 List of References.........................................................................................................................14 Chapter I Introduction EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 4 The fashions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reflects the spirit of the time, decades of change, with political and social shifts that can be seen in the evolution of women’s dress. In its evolution, fashion was influenced by art and thought and by the Baroque and Rococo artistic styles. The major European powers were France and England and these countries were the inspirational force of fashion. Writers of the period were amazed of the rapidity with which new fashions were introduced (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 233). The considerable development of industry and trade made great contributions to costume and how fast it started changing in the coming decades (Boucher, 1982, p. 291). The style of women’s dress of this time was abundant, exaggerated, luxurious and anything but practical. Purpose The objective of this paper is to describe women’s fashion garments in the seventeenth and eighteenth century of the aristocracy. Particularly in France, the effects on England, and vice versa. It describes the major garment and silhouette changes of the time. The major historical events are used to correlate with the fashions of the time. This paper strives to describe the evolution of dress and the different garments that were worn in different time periods. This is the time when fashions started changing rapidly and some even say it was the beginning of true fashion in society, because of the new inventions and the decreased dominance of the courts. Chapter II 1600-1700: The Seventeenth Century EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 5 Women’s Dress Spanish influence continued into the 1600s. The ruffs developed in the Renaissance were still worn and became enormous (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 237). The invention of starch replaced the use of the wire frames that supported the large Medici collars (Laver, 2012, p. 103). The wheel farthingale was also still being worn but had flattened slightly in the front, leaving the sides with the most width and fullness. Slashing on the bodice sleeve, which were still voluminous was apparent. The bodice had a U-shaped stomacher (Totora & Eubank, 2010, p. 261). The Spanish style lasted until about 1620. The French would now take over fashion influence across Europe and even the New World (Kelly & Schwabe, 2002, p. 121). Mid Seventeenth Century “Before this century, any fashion set by the nobility was certain to catch on, but gradually the burghers began to wear the stuffs reserved for nobles, forcing them to change constantly” (Boucher, 1982, p. 254). It was usually very clear what someone’s social rank was based on their dress. With faster and more efficient ways of producing fabrics, all classes could spend money on the recent trends. Some governments tried to pass various sumptuary laws restricting the wearing of jewels, silk clothes, velvet and other rich materials from farmers and other lower class societies. These laws never stayed long, or were replaced by abundance of less expensive attachments like braids, rosettes, embroidery, and bows. There was a shift in styles after 1630, it was considered the deflating style. Paddings, slashes, ruffs, and farthingales were abandoned by women. These styles were old-fashioned, only older women would still wear them. The style and silhouette became more natural and loose, yet still elaborate in some parts. The ruff was replaced by a long series of richly laced collars sloping down over the shoulders (Gorsline, 1952, p. 66). It EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 6 was a fallen collar. The main garments were the bodice, petticoat, and the gown. The bodice was low and v-shaped, squared, or horizontal at the bosom. The horizontal neckline was the most popular in the mid seventeenth century. The waists were generally higher, tied with a ribbon, and the shoulders were broad. Sleeves were full and usually had a turned back piece of lace or a ruff below or above the elbow. Virago sleeves were popular, they were full, paned, and tied into puffs at different sections down the arm (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 253). Rosettes were tied on the sleeves or the waist. The skirt was full and the gown was usually spilt in the front middle to show the underskirt, which was usually made of more expensive heavy silk satin (Gorsline, 1952, p. 66). Late Seventeenth Century The last half of the seventeenth century saw even more changes in styles. A long-pointed, wasp-waist bodice became popular. The waists became tighter and the outline of the figure was stiffer and narrower (Laver, 2012, p. 112). The silhouette was slimmer. Shoulders were shown more. Sleeves were set low on the shoulder, opening into a full puff that ended below the elbow. Skirts were either closed or open at the front to show the underskirt like before. The difference was the open skirts were pulled back to the rear or caught back in intervals by ribbon-ties (Kelly & Schwabe, 2002, p. 172). This, known as a bustle, looked like the pulled back curtains of a stage. This allowed the underskirt to be shown usually of a bright color. The century ended with an increase of decoration. The front bodice usually showed the corset and had the pronounced vshape at the waist. They were heavily decorated with bows or a separate stomacher was tied or pinned at the front of the corset to vary the appearance of the different dresses a lady might own (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 255). Skirts had so many layers and were embroidered heavily that support of whalebone or metal was needed. At the end of the century almost all outer skirts or EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 7 gowns were split in front and looped back in drapes into a long back train. This decade is also when you first see the manteau or mantua, a dress cut in one length from shoulder to hem, and worn over the corset and underskirts. This dress always formed a bustle at the back. Previously the bodice and skirt were cut separately and then sewn together. This dress might have originated from the middle east (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p.255). French influence in england. It is important to note that Charles II of England fled to France as the English Civil War (1642-1651) was in effect. He reigned from 1600 to 1685 (Gorsline, 1952, p. 67). When he returned to claim his throne, he brought with him all the French court fashions that he observed and they became a major influence in England. This continues France’s dominance of a cultural leader. Conclusion The seventeenth century ended with an increase of decoration and an increase in exaggerated styles, like the skirts that were so layered and heavy, support from whalebone was used underneath them. Precious stones, gold embroidery, braids and fringes were used in abundance to decorate fabrics (Boucher, 1982, p. 258). This was all a statement of wealth and flaunting ones idleness. Conspicuous leisure comes to a peak later in the eighteenth century. Chapter III 1700-1750: The Early Eighteenth Century Historical Background EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 8 French fashion supremacy continues in the beginning of the eighteenth century which is evidenced across civilized Europe. The French not only influenced fashion, but also literature, decorative arts, philosophical theories and an international language (Tortura & Eubank, 2010, p. 266). The Spanish Court circles known for their traditional dress, finally follow the French trends (Kelly & Schwabe, 2002, p. 199). There is a general change in European civilization. A true society begins to emerge rather than a ‘class’ of people. “The considerable development of industry and trade made such great contributions to costume that they might almost seem to have taken place solely with costume in view” (Boucher, 1982, p. 291). New inventions increased outputs of cloth, such as, the flying shuttle, spinning Jenny, cotton-spinning loom and more. Scientific research also made progress in textiles. In 1720, Sir Isaac Newton was the first to isolate the color spectrum into red, yellow, and blue. Textiles gained a wider array of colors to include not only the bright colors of the previous century, but also muted shades and strong tints (Boucher, 1982, p. 293). International trade brought Asian influences to Europe. There were silks from China, cottons from India along with their cultural designs. Luxury and inventiveness of costume brought the classes closer because tailors, fabric weavers, shoe makers, wig makers all worked with aristocratic society. Women’s Dress The Baroque style gave way to the more delicate and curvilinear forms of the Rococo style (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 265). The long slender bodice with a full skirt and even more fullness in the back continued until about 1720. The v-shaped stomacher was still in use. Corsets were sometimes shown and they laced up the back, or both the back and the front (Tortora & Eubank, 2010, p. 279). EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 9 Sacque Gown There was also a new shapeless type style called the sacque dress. This was an unbelted gown and had a loose bodice. It had box pleats starting at the back shoulder falling all the way to the hem. The gown was worn over dome or cone-shaped hoops called panniers, making the silhouette very wide all round. The width of the hoops worn underneath varied, depending on taste of silhouette. The pleated back was known as the Watteau pleat, which was a deep box pleat and ended in a long train (Peacock, 1991, p. 130). The dress was still worn over a corset or decorative stomacher (Laver, 2012, p. 130). This back pleat detail revived in the 19th century and lasted into the early 20th century, as a feature on tea-gowns. Watteau was a name given to many different garment types such as Watteau body, costume, and robe (Cumming, Cunnington, & Cunnington, 2010, p. 222). It derives from the French artist Antoine Watteau, who was a very popular Baroque and Rococo style painter. Paniers. These hoops were formed with usually three or more tiers of whalebones. They took on different shapes in the eighteenth century. From oval bell Figure 3.1 Sacque Gown (Boucher, 1982, p. 295) shape, funnel-shaped, dome-shaped, and elbow paniers where the wearer could rest her elbows on them (Boucher, 1982, p. 296). These stayed in fashion for the first thirty years of the century, even though they were greatly inconvenient and uncomfortable. The paniers after 1750 modified to become two separate parts. Known as a double panier, they were attached to each side of the waist by ribbons. They could be lifted under the arms to walk through doorways (Boucher, 1982, p. 296). The wide skirts were usually for the French Court. Robe à la Française EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 10 This is the gown that was made for the double paniers. It had a fitted front with an open bodice. The bodice usually had an echelle. This was a series of graduated ribbon bows from the Figure 3.2 Side Loops (Paniers) Gorsline, 1952, p. 112) bosom to the waist. The bows became smaller towards the waist (Kelly & Schwabe, 2002, p. 214). The overgown opened widely over the petticoats. This gown had a tight sleeve to the elbow, ending in a pagoda style with one or more flounces. At the cuff of the sleeve was the engageante, which were two or three graded flounces of lace. All women wore this type of dress and it varied on richness of fabric and decoration (Boucher, 1982, p. 296). This gown also had the Watteau full box pleats at the back. The width of the hoops could be as long as fifteen feet. Figure 3.3 Robe à la Française (Boucher, 1982, p. 298) Chapter IV 1750-1800: The Late Eighteenth Century Women’s Dress After 1770 the robe à la Française modified a bit for everyday wear but was reserved for ceremonies (Boucher, 1982, p. 299) The paniers were replaced by hip pads. This slimmed down the silhouette and showed off the waist. This modification was a decreasing emphasis on the EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 11 popular French Court style (Laver, 2012, p. 139). There was an increasing adoption of English country clothes that was worn for everyday life. The trend was more practical and simple. “The English style was characterized by a close fit over the waist and a boned bodice, the fullness of the skirt was pushed toward the back over a false rump” (Steele, 1998, p. 35). False rumps were filled with cork or other materials to create a cushion. This major English garment was called the robe à l’Anglaise. It had various styles of bodice. The stomacher front used an attached piece. The buttoned front had a false waistcoat sewn into the inner lining of the bodice. There was also a closed front style (Cumming, Cunnington, & Cunnington, 2010, p. 174). The silhouette of the bosom being emphasized by tied kerchiefs and the false rump made the wearer look like a pouter pigeon (Gorsline, 1952, p. 99). The skirt opened wide over the underskirt. Shortly after, the coatdress or the redingote dress appeared. It had a fitted bodice, buttoning in front, with pointed lapels, and the skirt opened widely over the underskirt (Boucher, 1982, p. 299). Fashion Plates Fashions spread from word of mouth and by the world travelers. Dressmakers would travel every year and make miniature dolls of what the fashions were in that particular country. This changed with the fashion plates, especially from La Galerie des Modes of 1778-1787. Large variations of female attire and the ability to spread them throughout Europe changed the pace of fashion. The plates were published in periodicals with colored pictures. As the nineteenth century rolled on, almost all households had fashion magazines (Laver, 2012, p. 147). French Revolution, the end of the Eighteenth Century EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 12 At the end of the century there was a sudden reversal in fashion’s. The French revolution could be blamed for this change. “The clothes worn before and after the Revolution are so different that we seem justified in assuming that the Revolution somehow caused this profound sartorial change” (Steele, 1998, p. 37). There were no more embroidered coats and brocaded gowns. Paniers, bustles, and corsets were all abandoned. The Robe en chemise was now worn, it was pseudo-classical. It looked like an undergarment, it had a high waistline, was very transparent, and was worn with tights underneath (Laver, 2012, p. 152). This simple frock was offensive to people who believed it was meant for privacy only. Conclusion Clothing in the 17th and 18th-centuries was a means of showing ones wealth, especially the nobility. Conspicuous consumption is evidenced in the rich fabrics and details. Conspicuous leisure is evidenced in the wide panniers and heavy skirts. Changes in fashion occurred much more rapidly in this time due to increased innovation and the increase of published fashion plates. The fashions evolved and the silhouettes went through many changes of inflation and deflation. The 17th century ended Figure 4.1 Robe en chemise (Laver, 2012, p. 152) with an increase in ornamentation and the mantua cut dress. The 18th century started with the sacque dress. A very loose garment with box pleats hanging from the back. Then in the middle years, the exaggerated hips were popular seen in the robe à la Française. These styles were the greatest representation of conspicuous leisure and consumption because they were highly decorated, rigid, and high maintenance. The panniers were replaced with hip pads at the end of the century. The skirts were swung back like a stage curtain. Finally the century ended with the EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 13 French Revolution that affected not only the relationship between the aristocracy and the rest of society but also the costume of France and Europe. The result was a gown that looked like undergarments and seemed inspired by the classical period. List of References Boucher, F. (1982). 20,000 years of fashion the history of costume and personal adornment. (pp. 251-330). Flammarion, Paris: Harry N. Abrams, INC., Publishers. Cumming, V., Cunnington, C. W., & Cunnington, P. E. (2010). The dictionary of fashion history. (pp. 79-222). New York, New York: Oxford International Publishers Ltd. Gorsline, D. (1952). What people wore a visual history of dress from ancient times to twentiethcentury america. (pp. 65-99). New York, New York: The Viking Press. Kelly, F., & Schwabe, R. (2002). European costume and fashion: 1490-1790. (pp. 121-219). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. Laver, J. (2012). Costume and fashion a concise history. (5 ed., pp. 103-153). New York, New York: Thames & Hudson Inc. EVOLUTION OF WOMEN’S COSTUME 17TH-18TH CENTURY 14 Peacock, J. (1991). The chronicle of western fashion. (pp. 129-152). New York, New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated. Steele, V. (1998). Paris fashion a cultural history. (2nd ed., pp. 34-40). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. Tortora, P., & Eubank, K. (2010). Survey of historic costume. (pp. 229-289). New York, New York: Fairchild Books.