Chapter 3 Lecture-1

advertisement

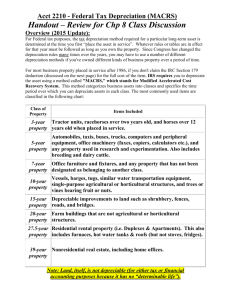

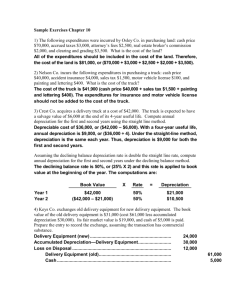

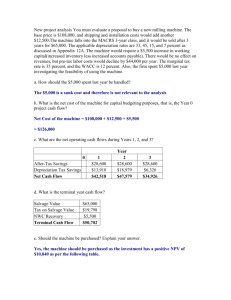

Chapter 3 Lecture Chapter 3 is concerned with using financial statements to estimate the cash flow (cash in minus cash out) of the firm. One of the key aspects of estimating cash flow involves the effect depreciation has on reducing taxable income, which reduces the firm’s taxes which, in turn, increases the cash the firm can keep. The net effect is that depreciation expense increases the firm’s cash flow by reducing tax expense. A very specific method is used to compute depreciation for tax purposes. It is called Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery system (MACRS). It is loosely related to the double declining balance method of depreciation used for financial reporting purposes. MACRS MACRS classified long-term assets (those expected to last more than one year) into a number of classes. These are shown in Table 3.1 on page 93 of your text. Take a minute to review the table. Suppose you own a plant nursery and your firm buys a light-duty truck to make deliveries to customers. Suppose further this truck costs $50,000. You examine the table and find the truck is listed in the 5-year property class. This means the truck must be depreciated as a 5-year asset for tax purposes. Its worth noting that IRS regulations allow you to depreciate not just the cost of an asset ($50,000 in our example), but also any shipping and installation charges. Let’s assume all that is already included in the $50,000 price of the truck. Our next step is to compute the depreciation-expense-deduction the IRS allows you to take each year. Now we must examine Table 3.2 on page 94 which provides the depreciation rates for each of the property classes listed in Table 3.1. Since your truck is in the 5-year property class, we will be looking at the column labeled “5 years”. Before we proceed, notice something interesting. The truck is in the 5-year class, but if you look at the 5-year column in the table, you will notice the truck is actually going to be depreciated over 6 years, not 5. In fact, all the columns in the table have one extra year. Why is that? The reason is the half-year convention. As I mentioned previously, MACRS depreciation rates are loosely based on the double declining method of accounting. Recall that when an asset is depreciated using double declining balance, it is being depreciated at twice the straight line rate. For an asset expected to last 5 years, the straight line method would tell us to depreciate 1/5th (or 20%) of the asset each year. If double declining balance were used, we would depreciate 40% of the assets cost the first year. Now look at the depreciation rate for year 1 in the 5-year column. It says 20%, not 40% as we would expect. The reason for this is that the IRS gives everyone ½ year’s depreciation the first year regardless of when the asset is purchased. Some firm’s will buy their trucks at the beginning of the year, some will buy their’s at the end. The IRS assumes on average, firm owners will buy their trucks in the middle of the year. This is called the half-year convention. Because of the half-year convention, there will be a portion of the asset that has not been depreciated after the 5th year. This remaining depreciation is taken the 6th year. Finding the depreciation expense under MACRS is easy. All you do is multiply the assets depreciable basis (cost + shipping +installation) by the percentage rate shown in the table for that year. For our $50,000 truck, the depreciation expense we could claim each year would be Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rate 20% 32% 19% 12% 12% 5% Depreciation Expense $50,000 X .20 = $10,000 $50,000 X .32 = $16,000 $50,000 X .19 = $9,500 $50,000 X .12 = $6,000 $50,000 X .12 = $6,000 $50,000 X .05 = $2,500 Notice if we sum the depreciation expense for all six years, we get $50,000, the cost of the truck. Free Cash Flow The free cash flow of the firm is the amount of cash left after the firm pays its operating expenses, taxes, and pays for any shareholder-wealth increasing investments in current and fixed assets. What’s left over is cash the firm does not need and is therefore available for distribution to investors. Remember investors include both the debt holders and the equity holders of the firm. The debt holders are entitled to receive the amount they lent the firm plus interest. The equity holders should (notice I did not say will) receive what remains since the firm has no use for it. This remainder can be paid to shareholders in the form of dividends or the firm can use it to purchase the firm’s stock from shareholders in the open market. My personal preference would be for the firm to purchase its own shares in the open market. That way, there’s no drastic change in dividends (investors don’t like a lot of volatility in dividends) and only those shareholders willing to sell shares receive cash. This is important. Cash disbursements to shareholders of any kind are taxable. As a shareholder, I may not want a dividend just now because I may be in a high tax bracket and after I pay tax on the dividend relatively little will be left. Having the firm repurchase shares allows only those shareholders willing to pay the tax now (on any capital gains they have realized) to do so. Sometimes managers get confused about what they are supposed to do with free cash flow. They are supposed to find a way to get that cash to investors. However, sometimes managers “forget” that and instead spend the cash in ways that have nothing to do with maximizing shareholder wealth. For example, they may use the cash to pay for perquisites for themselves (e.g., expensive and elaborately decorated apartments, “loans” to managers that never have to be repaid, jets, limousines, etc.). Sometimes managers will use these funds to make diversifying acquisitions (Peter Lynch, former manager of Fidelity’s Magellan fund calls these “deworsifying” acquisitions because they almost always result in lower share prices: managers simply aren’t competent to manage firms outside their own industry) or to simply to increase the size of the firm even those these may not increase shareholder wealth. Why would a manager want to make a diversifying acquisition or increase the size of her firm if these actions do not increase shareholder wealth? Managers sometimes make diversifying acquisitions to reduce the volatility of the firm’s cash flow. That sounds like a good idea doesn’t it? Actually diversifying acquisitions are usually a terrible idea at the firm level. If shareholders want diversification, they can achieve it much more easily and cheaply on their own simply by purchasing shares of firms in other industries. Why would a manager want to increase firm size even though this may not be consistent with maximizing shareholder wealth. A manager might do this because she believes that her compensation is tied, at least in part, to the size of the firm. Again, managers are not perfect agents for shareholders because, just like us, they are human. Measuring Free Cash Flow The method for finding a firm’s free cash flow is shown both in the text (see pages 98 through 102) and in the PowerPoint slides for chapter 3. However I will provide a short exposition of the formula for free cash flow here. My purpose here is to highlight the relationships between free cash flow and the variables in the formula for it. Free cash flow equals FCF = OCF – NFAI - NCAI Where OCF equals operating cash flow: Operating cash flow results from the firm selling and producing its product or service. Usually, this will be the firm’s major cash inflow. Operating cash flow equals OCF = EBIT(1 – Tax Rate) + Depreciation Expense NFAI stands for net fixed asset investment. NFAI is the amount the firm spent on fixed assets during the most recent year. Net fixed assets equals NFAI = Change in Gross Fixed Assets In words, NFAI = Gross fixed assets for most recent year minus gross fixed assets for the previous year NCAI stands for net current asset investment. This represents the amount the firm spent on current assets during the most recent year. Net current asset investment equals NCAI = Change in CA – (Change in (A/P + Accruals)) In words, NCAI equals the difference between current assets in the current year and current assets in the previous year minus the sum of accounts payable and accruals in the current year minus that same sum in the most recent year. Let’s spend some time looking at the NCAI formula. The change in current assets represents the amount of cash the firm spent on current assets. However, the firm did not have to use its own cash to fund the change in current assets. It was able to borrow some of that amount from its suppliers in the form of accounts payable and its workers and the government in the form of wages and taxes payable. So the difference, NCAI, represents the amount of its own money the firm spent on current assets after the interest-free loans provided by suppliers, workers and governments. You might wonder why the formula isn’t simply NCAI = Change in CA – Change in CL. There is a very good reason for that. First, we only want to include those current liabilities that spontaneously change when current assets change (the short-term notes payable appearing in the current liabilities section do not spontaneously change with current assets: the only way notes payable changes is when the firm purposefully borrows from a bank). Second, notes payable represents an obligation to an interestpaying investor in the firm (in this case a bank). In this sense, the funds raised through short-term notes payable are not “free”. The firm must pay these funds back with interest. An interesting exercise is to imagine what would happen to the free cash flow calculation if notes payable were mistakenly included in the formula as a current liability. Would this cause free cash flow to be overstated or understated? If you guessed overstated, you would be correct. If effect, this would mistakenly increase the amount of “free” money available to the firm, thereby reducing the amount of the firm’s own money spent on current assets, resulting in a higher free cash flow. If effect, we would be classifying short-term bank loans as interest free by mistake implying banks were not really investors in the firm. We would be misled into believing the firm had more free cash flow than it did. But bank loans are not free and do not spontaneously rise with current assets so they are not included in the calculation of free cash flow.