Lecture 1 : The Ricardian Model of Comparative Advantage

advertisement

International Trade Theory

Lecture 1 : The Ricardian Model of Comparative Advantage

Kornkarun Kungpanidchakul, Ph.D

Opportunity cost

- Comes from the next best foregone alternative

- To find the opportunity cost, you must have more than one alternative, goods or

activities

Adam Smith (wealth of Nations, 1776)

- introduces principles of division of labor and specialization among countries

- each country produces goods that it can produce more for the same level of

resources/time.

- “ law of absolute advantage”

Absolute Advantage: Country A has absolute advantage in good X comparing with

country B if country A can produce more units of good X than country B, given that both

countries have the same level of resources, technology and time.

Assumption:

1. Constant opportunity cost (linear PPF)

2. Two countries with one factor “labor”

3. Two commodities (suppose Fish and Chips)

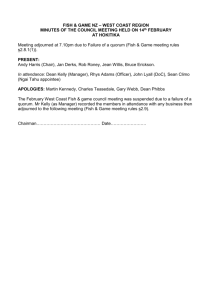

Country

Canada

Japan

Amount produced / unit of labor

Fish

Chips

100

50

50

150

So Canada has absolute advantage in producing fish and Japan has absolute advantage in

producing chips.

What is Adam Smith’s suggestion?

Canada produces only fish and Japan produces only chips. Then trade pattern is

Canada exports fish, Japan exports chips.

The Ricardian Model of Comparative Advantage

Consider the following table,

country

Canada

Japan

Amount produced / unit of labor

Fish

Chips

100

160

50

150

Opportunity Cost

Fish

Chips

1 F= 1.6 C

1 C= 5/8 F

1 F=3 C

1F =1/3 C

Canada has absolute advantage in both Fish and Chips. Therefore, according to

absolute advantage, no trade occurs.

David Ricardo introduced principle of “Comparative Advantage” or

“Comparative Cost”

Assumptions:

1. Labor is only production factor. The technology is constant returns to scale.

2. Identical tastes in both countries. Therefore, relative prices are solely determined

by supply side or technology.

Example 1: Suppose that there are two countries, namely Canada and Japan. They have

the total level of resource of L and L* respectively.

Country

Canada

Japan

Amount produced / unit of labor

Fish

Chips

1

1/2

1

1

Opportunity Cost

Fish

Chips

1F = ½ C

1C = 2 Fish

1F = 1 C

1C = 1F

Comparative Advantage

Country A has comparative advantage in good X comparing with country B if

country A can produce good X with the lower opportunity cost.

Define the formal notation of comparative advantage. Given that aLF is the unit

cost required to produce fish, aLC is the unit cost required to produce chips. Then

*

a LF a LF

* means that the opportunity cost of fish in Canada is lower than the

a LC a LC

opportunity cost in Japan. Therefore, Canada has a comparative advantage in fish while

*

Japan has comparative advantage in chips. If a LF a LF

, Canada has an absolute

advantage in fish.

Autarky Equilibrium

Production Possiblity Frontier: A curve showing all combinations of two goods that

can be produced for given resources and technology. The slope is opportunity cost.

Fish

-

Perfect substitutes

Constant opportunity

cost

Chips

In autarky economy, the country will product at the point that the indifference

curve is tangent to PPF.

Fish

A

Chips

Equilibrium Condition:

1. pC waLC

2. pF waLF

3. L LF LC

Therefore, if we have interior solution, 1. and 2. implies:

pC waLC a LC

p F waLF a LF

Trading Equilibrium

There are three possible types of equilibrium. Let (

pC w

) is the world relative

pF

price, then we have:

p

a*

a

1. If ( C ) w LC

LC , then Japan diversifies between fish and chips while

*

pF

a LF a LF

Canada specializes in Fish.

a*

p

a

2. If LC

( C ) w LC , then both countries specialize with Canada specializes in

*

pF

a LF

a LF

fish and Japan specializes in chips.

a*

p

a

3. If LC

( C ) w LC , then Japan will specialize in chips while Canada

*

pF

a LF

a LF

diversifies.

In all equilibriums, Canada exports fish while Japan export chips. Therefore, even

diversified economy, patterns of international trade is specialized in the Ricardian model.

The Gains from Trade

*

pC w a LC

a

) * LC , Canada gains from trade since it can consume

pF

a LF a LF

outside its own PPF.

1. When (

F

C

F

Canada’s PPF

C

Japan’s PPF

2. When

*

a LC

p

a

( C ) w LC , both countries can consume outside its own PPF.

*

pF

a LF

a LF

F

C

Canada’s PPF

F

C

Japan’s PPF

F

*

a LC

p

a

3.When * ( C ) w LC , only Japan’s PPF shifts up.

pF

a LF

a LF

C

Canada’s PPF

F

C

Japan’s PPF

Comparative Advantage with Many Goods

Suppose instead that both Canada and Japan consume and produce N different

goods, for good i ={1,…,N}. We still assume that each country has only one factor of

production which is labor. Suppose that a Li and a Li* are unit labor requirement for good i

of Canada and Japan respectively.

a

To analyze trade, we calculate Li* , the ratio of Canada’s unit labor requirement to

a Li

Japan’s and rank the good so that the lower the number, the lower the ratio, i.e.

a

a

a L1

... Li* .. LN

(1)

*

*

a L1

a Li

a LN

Let w and w* be the wage rate per hour in Canada and Japan respectively. The

relative wage is used to determine a set of goods produced in each country. Good i will

a

a

w*

w*

be produced in Canada if Li*

and will be produced in Japan if Li*

. Suppose

a Li w

a Li w

a LJ w*

, then all the goods to the left of J will be

*

a LJ

w

produced in Canada and all the goods to the right of J will be produced in Japan. The

that good J {1,..., N } is such that

relative wage is determined by the relative demand for labor and the relative supply of

labor. The relative demand for labor can be derived from the relative demand for goods

and have downward sloping. The relative supply of labor is fixed since L and L* are

given.