Accounting - Penn APALSA

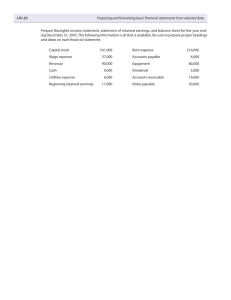

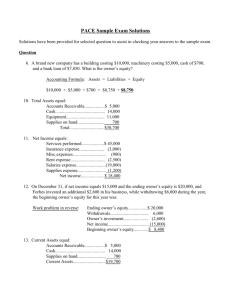

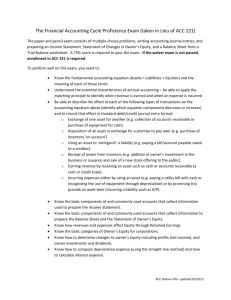

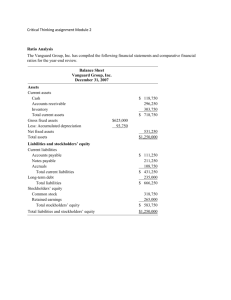

advertisement