case studies - Terrell Neuage

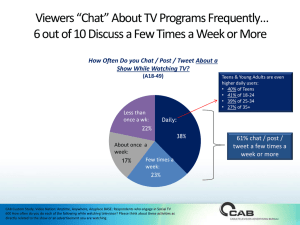

advertisement