NICs Lessons of Economic Growth

advertisement

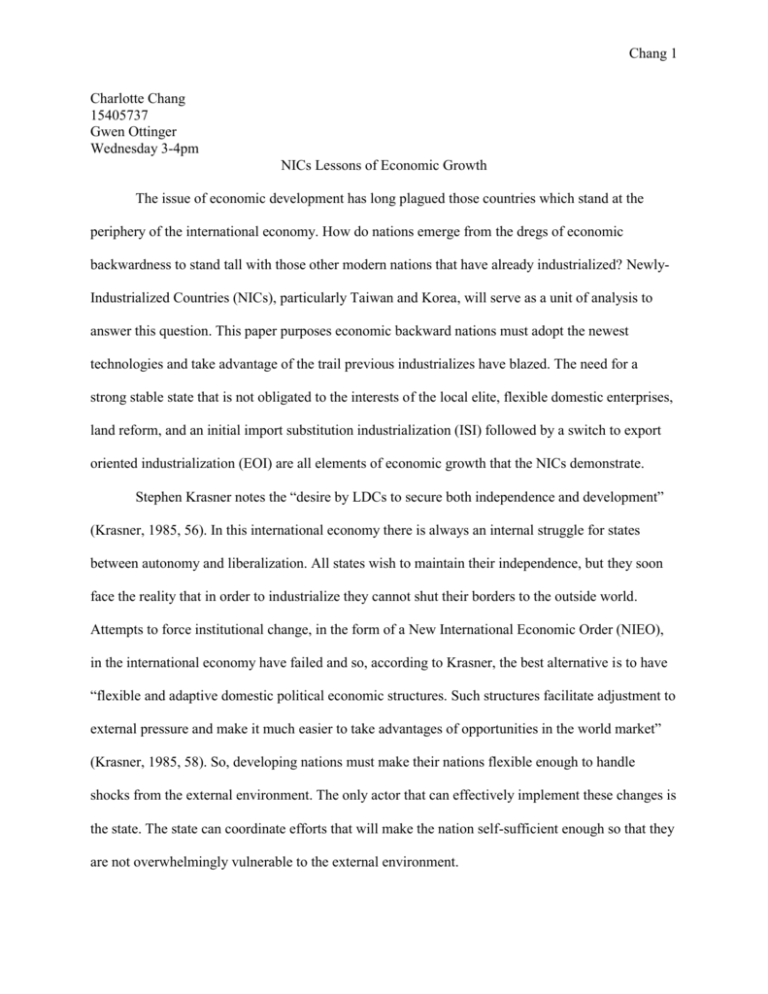

Chang 1 Charlotte Chang 15405737 Gwen Ottinger Wednesday 3-4pm NICs Lessons of Economic Growth The issue of economic development has long plagued those countries which stand at the periphery of the international economy. How do nations emerge from the dregs of economic backwardness to stand tall with those other modern nations that have already industrialized? NewlyIndustrialized Countries (NICs), particularly Taiwan and Korea, will serve as a unit of analysis to answer this question. This paper purposes economic backward nations must adopt the newest technologies and take advantage of the trail previous industrializes have blazed. The need for a strong stable state that is not obligated to the interests of the local elite, flexible domestic enterprises, land reform, and an initial import substitution industrialization (ISI) followed by a switch to export oriented industrialization (EOI) are all elements of economic growth that the NICs demonstrate. Stephen Krasner notes the “desire by LDCs to secure both independence and development” (Krasner, 1985, 56). In this international economy there is always an internal struggle for states between autonomy and liberalization. All states wish to maintain their independence, but they soon face the reality that in order to industrialize they cannot shut their borders to the outside world. Attempts to force institutional change, in the form of a New International Economic Order (NIEO), in the international economy have failed and so, according to Krasner, the best alternative is to have “flexible and adaptive domestic political economic structures. Such structures facilitate adjustment to external pressure and make it much easier to take advantages of opportunities in the world market” (Krasner, 1985, 58). So, developing nations must make their nations flexible enough to handle shocks from the external environment. The only actor that can effectively implement these changes is the state. The state can coordinate efforts that will make the nation self-sufficient enough so that they are not overwhelmingly vulnerable to the external environment. Chang 2 Krasner notes that the East Asian NICs have “adopted aggressive export-oriented strategies. This required effective government capability or the possession of developed flexible markets” (Krasner, 1985, 49). This will mitigate the shocks from the external international environment. “During the 1970s the NICs were able to cope with restrictions imposed by INs by moving into new product lines and diversify their exports” (Krasner, 1985, 50). In contrast, one can examine the case of the oil-exporting countries. While blessed with an incredible natural resource, this blessing can turn into a curse. The oil-exporting nation becomes dependent on that single industry and never builds up other industries. This leads to a rigid economic structure that is not suited to the fluid nature of the international economy. The OPEC countries “do not have the economic or political capabilities to adjust. The global system showered them with riches in the 1970s but they still remained hostage to external events over which they had little control” (Krasner, 1985, 51). The case of the NICs and the OPEC countries illustrates the need to diversify industries. In regards to the domestic situation, the most important factor is the state. To be more specific, there must be the concept of a nation. For instance, in Africa, arbitrary colonial boundaries have created hodgepodge ethnic states that are often at war and require vast amounts of resources to deal with those insurrections. Most of the NICs were islands (Taiwan) or countries that already had the concept of a nation (Korea). While it seems trivial, the idea of a nation is important because it eliminates the costs of state-building. Those costs that enter into maintaining order and solving ethnic wars could have been used to develop domestically. Therefore, there must be a legitimate state before any development can take place. State authority and intervention are key factors in the development of a nation. This authority allows the government to develop the nation. As distasteful as it is for Western ideology, an authoritarian government, as opposed to a democracy, is probably the most efficient means for a state to implement plans for growth. The reasoning behind this assertion is authoritarian governments are not constantly worried about re-election and so will not pander to the interests of the elites; the state Chang 3 can then concentrate on the task of economic development. There is a need for short-term suffering before growth in the long-run can be established and authoritarian governments are better suited to administer this economic suffering to the people. The NICs are an excellent example of how state coordination of an economy provided stability and a consistent long-term vision for economic growth. In the case of Korea, “because this regime has been authoritarian…it could hold down wages and consumption, largely ignore rural interests, and concentrate on rapid development through industrialization” (Cumings, 1987, 73). The Korean case is illustrative of the necessity for a strong state to push through the policies needed for economic growth. While the idea of democracy is often seen as a panacea of sorts to the West, those fledgling states that have yet to industrialize would be better served by a strong authoritarian state that is dedicated to economic growth; cases of extreme corruption such as the Mobutu and his utter fleecing of the Democratic Republic of Congo (also known as Zaire) do no count as such regimes. In addition to being strong enough to implement unpopular changes, it is best if the government does not have ties to the elite. In the case of Taiwan, a transplanted government from the mainland allowed the Kuomintang (KMT) to implement its long-run plans for growth; because the Chiang Kai-shek led government did not have ties to the local elite it was free to implement its own policies without concerns of obligation to the local elites. Cumings calls this type of state Bureaucratic-Authoritarian Industrializing Regimes (BAIRs). “These states are ubiquitous in economy and society; penetrating, comprehensive, highly articulated, and relatively autonomous of particular groups and classes” (Cummings, 1987, 71). In Latin America, where there is a strong connection between the bureaucrats and the local elite, it is much more difficult to institute changes that the local elite do not agree with. As many industrializing policies are unpopular among the elite, this makes it difficult to make these fundamental changes. The state must be capable of acting autonomously to make the best decision for the whole of the nation, without certain sectors of society hounding and dogging its every move. A good example of the need for a breakage between the state Chang 4 and the local elite is the need for land reform. Land reform in Taiwan “aided the productivity of agriculture because redistributed land went primarily to entrepreneurial, productive, relatively rich peasants” (Cumings, 1987, 65). This land reform increased productivity which helped set the stage for nationwide growth. It also helped to foster a sense that the government really is trying to help the nation as a whole and not sectoral interests. Furthermore, the state should invest heavily in human capital. It is unrealistic to assume that within a generation the entire nation will be college-educated scholars but basic primary education will help the economic development cause. This investment in primary education may be costly initially, but it will eventually pay dividends as a basic level of education will help production immensely. Just the ability to read instructions, manuals, or announcements from the government will set the stage for an even greater educated workforce in the future and for innovative thinking. An educated workforce is more likely to innovate and to raise the standard of the nation as the basic factor endowments increase. In the NICs, the government directed its limited public funding of postsecondary education “on technical skills, and some HPAEs imported educational services on a large scale, particularly in vocational and technologically sophisticated disciplines. The result of these policies has been a broad, technologically inclined human capital base well-suited to rapid economic growth” (World Bank Report, 1991, 15). Labor repression is also needed to grow economically. Again, as distasteful as it seems, if there was constant upward pressure on wages it would be very difficult to develop industries because costs would continually rise. Ergo, while Marxists would no doubt cry foul, it is necessary to repress the labor. Yes, it is undoubtedly unfair, but someone must bear the costs of growth and labor happens to be that unlucky party. By doing so, the state will accomplish two things. Firstly, it will lower costs for its domestic companies thereby making them more competitive. Secondly, the lower wages will serve as an inviting factor for foreign investors. When nations decide to switch to an EOI strategy and wish to attract more FDI then the foreign investors will then bring their capital, but, more Chang 5 importantly, their technology as well. Cheap labor is the competitive advantage of developing nations and the NICs understood this. “Taiwan was integrated into the international system on the basis of its competitive advantage in low-wage labor” (Haggard and Cheng, 1987, 115). However, the need for foreign capital is questionable. The NICs developed without an overwhelming amount of foreign direct investment (FDI) in the beginning. However, the NICs did receive a lot of aid and so the need for FDI must be questioned. While there was some investment in the developing nations, other than Singapore, FDI as a share of gross domestic capital formation was not extraordinarily high. “Overall the role of foreign direct investment in capital formation, exports, and therefore ultimately growth itself proved relatively small. National firms were the backbone of industrial development” (Haggard and Cheng, 1987, 100). Liberals will say that once the state has established the basic infrastructure for economic activity the state should step back and allow market powers to take over. Gerschenkron disagrees with this assertion by using Russia as a historical case study. Peter the Great modernized his country but without a strong, capable state after his reign the country’s economy staggered. However, once the Soviets took control the strong coordination of the Communists efforts were able to jolt Russia out of its stagnation. Gerschenkron writes of Russia, “The retrenchment of government activities led not to stagnation but to a continuation of industrial growth” (Gerschenkron, 1962, 22). This illustrates the value of a strong state to coordinate economic development can be seen. Domestically, it is necessary to have a strong state that will be able to implement the unpopular reforms that are needed for the state to be prepared to industrialization. When first industrializing, the state must implement an import substitution industrialization (ISI) model. This will allow the local industries to develop and gain experience so that when they open the borders the domestic firms will be able to maintain their influence when foreign firms enter the market. Taiwan and South Korea undertook these models and were able to protect their local producers; they also offered incentives to facilitate increased productivity. In Taiwan, the state Chang 6 followed indicative planning, where it offered incentives such as offering better exchange rates, subsidies and other such inducements to reach certain targets. Other than incentives, the state must also promote the most recent technologies and take advantage of the so-called, “late developer advantages.” While that may see like an oxymoron, the main advantage of developing later is that there is a precedent set by other nations. A country can learn from previous mistakes that were made and pick and choose which existing technologies they would like to adopt. By doing so, the nation can leapfrog those growing pains the earlier industrializers went through. This compresses the amount of time it takes to industrialize. The ability to utilize the latest technology to propel the nation industrially and to shorten the industrialization timeframe constitutes key elements that late developers must undertake. “Industrialization always seemed the more promising the greater the backlog of technological innovation which the backward country could take over from the more advanced country. Borrowed technology…was one of the primary factors assuring a high speed of developing in a backward country entering the stage of industrialization” (Gerschenkron, 1962, 8). Therefore, the government of the developing states must push for integration of the latest technology. “It was largely by application of the most modern and efficient techniques that backward countries could hope to achieve success, particularly if they industrialization proceeded in the face of competition from the advanced country. The advantages inherent in the use of technologically superior equipment were not counteracted but reinforced by its labor-saving effect” (Gerschenkron, 1962, 9). Thus, those states should concentrate their activity in those industries in which the most recent technologic innovations have been particularly rapid. The states should also push the industries to reinvest rather than extracting the profits; a long-term goal of economic growth should be encouraged by the state. The state should protect its industries and subsidize them until they are ready to compete with the outside world. Once a state has reached a certain economic level its own markets no longer are sufficient for the domestic firms’ purposes; in such cases, the firms will want to start to participate in Chang 7 the international economy and export. At that point, it is time to open up the economy to international competition. The NICs implemented followed this model as they first instituted an ISI strategy and later switched to EOI. “In Korea and Taiwan a protective attitude toward domestic firm eliminated the threat of import competition or denationalization” (Haggard and Cheng, 1987, 99). During the ISI they did not allow foreign capital, but as they began the transition to an EOI strategy the need for foreign direct investment became more necessary. “In Taiwan and Korea the state supported local manufacturing firms through a period of ISI, which strengthened their capabilities until they could spearhead the export drive of the 1960s” (Haggard and Cheng, 1987, 117). This ISI strategy helped the states retain autonomy during development. If they had opened their borders and allowed widespread multinational corporations (MNCs) to enter the market then the state would have had lost some measure of its authority. Evans argues that the state can negotiate with the MNCs and try to get the most beneficial terms to their entrance but accomplishing this is easier in theory than in practice, especially for smaller states. While this may work for nations such as China and India, whose sheer size and economic potential make them desirable locations and gives them bargaining power, smaller nations are not so fortunate. As loathed as they are by some, the MNC is important in the development of states. “Industries in which the most important thing is access to universally applicable, rapidly changing technology that cannot be obtained on an open market are the domain of the multinationals” (Evans, 1979, 284). However, for developing countries who do not yet have the capacity to bargain or compete with the MNCs barriers should be erected during the ISI phrase so only limited MNC presence can be felt. MNCs should not be allowed in until the domestic economy has been developed enough. This will give the state a greater bargaining position and allow for a more equitable triple alliance that would have otherwise been achieved. The way in which they encouraged FDI was by establishing greater property rights and more open policies to attract the FDI. If investors feel that their rights will not be protected in a country, they will not invest in that country. Chang 8 The ISI strategy allowed the NICs to develop domestically before they shifted to the exportoriented strategy. This opening of borders will allow the domestic firms to compete internationally and test its mettle. These firms will become more and more efficient as they gain experience and contend in the international market. Therefore, in terms of the international economy, the developing state should first isolate itself from the international economy with an ISI strategy and then move to an EOI strategy. By raising protective barriers the nations can protect its domestic industries. The state should then offer incentives to stimulate innovation and growth within the industries. If these incentives are not offered than improvements in efficiency and increases in innovation may not occur. As the domestic industries grow they will reach a certain point where they are ready for integration into the world economy. At that point, the state should gradually open the doors for international competition. Along with this liberalization the state should also seek FDI by establishing secure property rights; this will assure foreign investors that their capital will be safe. The nation should also push for joint ventures between foreign investors and the local firms. This will allow transfer of technology as well as the assurance that at least some of the profits from these ventures will remain in the country rather leave as profits for a MNC. The state must be developed to a point where it has enough credibility in the international market for it to be able to bargain with MNCs. If the nation shows that it does need the MNC then it has more chips with which to bargain. There are several approaches to how nations should approach the problem of late development. This paper has taken an economic nationalist and a liberal approach. While the nation must eventually become integrated into the international economy to fully develop it is very difficult to do so when the nations are so disadvantaged. Liberals would like for the borders to be open and for the government to simply stand back. This approach will not be successful because of the shortrun oriented nature of the market. Market factors and considerations will consider the short-run profits and sustainability and will not necessarily undertake those policies that are best for the nation. Chang 9 Furthermore, the market is not a paradigm for allocative efficiency. Even the notoriously liberal World Bank in its report on the East Asian NICs admitted that government intervention and guidance can have a positive effect in the economy. The report states that “governments are more likely to do harm than good, unless interventions are market friendly” (World Bank, 1991, 12). This admission, however slight, is a testament to the success of the NICs. While liberal powers would prefer not to acknowledge state interventions, the influence of the state was undeniable. Likewise the economic nationalists underestimate the need for cooperation and integration into the international economy. Some issues arise with the aforementioned qualities of developing nations. The first is that, as with any model, it is just that: a model. While wonderful in theory the real world is not so kind. For instance, breaking away from the local elite is hardly simple; in fact, it may be impossible within certain contexts. Also, the NICs model is often said to be regionally and temporally specific. While this may be true, there are still some important lessons that can be learned from the “East Asian Miracle.” Miracle it may not be, but learning experience it is. Investment in human capital and high savings rates, as well as market-oriented decisions by a strong state are all lessons that other developing nations can take. The international economy is not the same it was when the NICs were developing but fundamental changes, such as investment in human capital, are good to implement in any temporal setting. Haggard notes that “although there are certainly lessons to be drawn from East Asia, we must keep firmly in mind the peculiarities of development there” (Haggard and Cheng, 1987, 128). It is those lessons that this papers attempts to present. Furthermore, I think it bears noting that the liberal approach is celebrated in the West but we are quick to forget out own past. While pushing fledgling nations to open up borders to trade we have forgotten our past. The United States was very isolationist and had protectionist policies up until recently and even now protects some of its industries. There is a certain selective memory as we condemn those small states who would dare to institute a protectionist stance. That being said, without some contact with other economies it is virtually impossible to develop economically; some Chang 10 integration into the international economy is needed for growth. Lastly, there is always an indigenous element to economic growth. Transportation of strategies must always be modified so they are more country specific. The East Asian culture, history political structure and economic practices differ greatly from those of Latin America. Despite all the similarities that political scientists will point out there will always be a local element to change. The aforementioned outline of procedures that must be taken for economic growth are based on the NICs experience and so may not be a perfect fit for other nations. Some would argue that the NIC experience can never be duplicated. I contend that the duplication of a model is a fruitless endeavor anyway because of the intrinsic differences amongst nations. What we can draw from the immensely successful NIC experience are fundamental changes that must occur and what types of state actions will help facilitate economic growth. These lessons can then be applied to those later developers. As Gerschenkron notes, it is important to use those late mover advantages to catch up more quickly with the earlier movers.