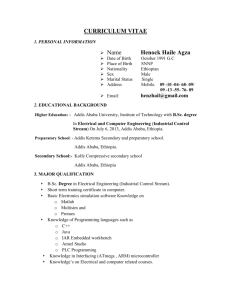

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

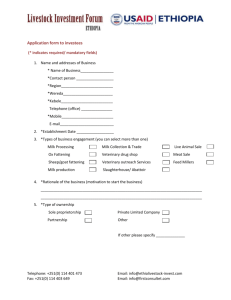

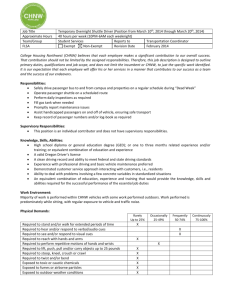

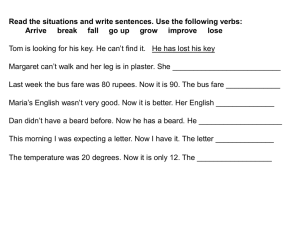

advertisement