Investigating zapping of commercial breaks and programming

advertisement

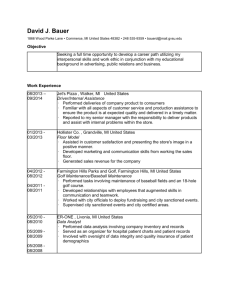

Page 1 of 8 ANZMAC 2009 Investigating Zapping of Commercial Breaks and Programming Content During Prime Time Australian TV Bryony Jardine, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science UniSA, Bryony.Jardine@marketingscience.info. Erica Riebe, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science UniSA, Erica.Riebe@marketingscience.info. John Dawes, Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science UniSA, John.Dawes@marketingscience.info. Acknowledgement: The authors wish to thank OzTAM and Network 10 Australia for supplying and providing access to the OzTAM data. Abstract Zapping is considered a significant problem for television advertisers and for the media that supply advertising space. This paper determines the proportion of an audience that is lost and gained in a typical minute of prime time Australian TV. Our objective in doing so is to describe the extent to which zapping is common within both commercial breaks and programming content. We show that although zapping is more likely during commercials, the behaviour is rare and is reasonably consistent across breaks in various environments. A timeseries regression of viewing data showed that a commercial break increases the natural or ‘baseline’ rate of viewer loss by around 1.6% points and it decreases the natural rate of gain by around 1.0% points. Keywords: television, zapping, switching, advertising effectiveness, advertising avoidance, VARX model ANZMAC 2009 Investigating Zapping of Commercial Breaks and Programming Content During Prime Time Australian TV Introduction Despite the increasing level of media fragmentation worldwide, television remains the most dominant media in terms of both viewership and advertiser spend (Green, 2007; James, 2009; Wilbur, 2008). While it has been reported that TV’s share of overall advertising spending has already peaked, it has also been suggested that television advertising will continue to occupy a large proportion of future advertising budgets (see Kwak et al. 2009). The effectiveness of advertising in this medium is therefore still of considerable interest to media buyers. In Australia, as in other countries around the world, ratings data is the currency by which TV advertising space is sold. The better the programs that stations offer, the better their ratings and the more they can charge advertisers for their space. Amongst industry practitioners, while it is widely acknowledged that TV advertising is sold on ratings of programs, it is also known that the actual audience for the commercials during those programs is smaller (see for example Danaher, 1995). Developments in technology have meant that it is now possible to separate commercial break ratings from program ratings (Atkinson, 2008), and so in some markets advertisers are now able to compare networks on their ability to retain an audience through the commercial break. It is therefore important to know the extent to which audience loss and gain during programs differs from that during commercial breaks, whether there is variation in this disparity, and whether any variation is systematically related to other variables such as whether competing stations are broadcasting advertising or programming at the time. Zapping The relatively broad literature on zapping (i.e. channel switching for live television (Kaplan, 1985)), suggests that it is most prevalent during commercial breaks. However, this literature has also produced inconsistent results in relation to the extent to which it occurs. Such inconsistency may reflect either that research studies in this area differ dramatically in the methods and measures of zapping that are used and/or that the extent to which audiences zap is affected by the conditions under which they watch. For example, in his work on TV ratings during commercial breaks, Danaher (1995) found that breaks on average result in 5% of the program audience being lost. Siddarth and Chattopadhyay (1998) suggested a rate of 2.7%; McConochie et al. (2005) found overall commercial avoidance was 7.3%, of which 4.1% was channel switching, and yet McDonald (1996) (who cites a number of studies with different methods) reported zapping rates in commercials of between 8% and 40%. In addition to the wide variation in reported rates of audience loss during commercial breaks, few studies have considered the amount of gain that may occur during commercials, as a result of the programming on competing channels. This is probably because most studies report change in net target audience rating points or gross rating points (TARPs/GRPs), rather than whether individuals change stations during ad breaks. To our knowledge, only Meurs (1998) reports both the audience gains and losses during commercials, concluding that, while there is an overall decrease in ratings during commercials, that this loss is the net result of both some gains and some losses in audience numbers. He reported an average audience loss Page 2 of 8 Page 3 of 8 ANZMAC 2009 in ratings (relative loss in GRPs) during commercials of 28.6% but a simultaneous gain of 7.1% (i.e. a net loss of 21.5%). Previous research also fails to highlight the commonality of zapping during programming content as opposed to that which occurs during commercials. Further knowledge is required about the extent to which zapping is a natural behaviour related to the act of watching TV, rather than something that is only brought about by the presence of advertising. Only then can we accurately detail the effect on zapping behaviour that is a result of advertising. For media companies, there are also questions related to how advertising breaks should be programmed. We seek to understand whether programming on competing stations affects audience loss and gain rates. If audience levels are affected by whether a competing station is broadcasting advertising, some ad breaks (i.e. such as the ones that occur when other stations are also advertising) may be preferable for advertisers. Meurs (1998) investigated this issue and found that an influx of viewers occurs when competing channels broadcast commercials. Our research is also particularly timely given the current pace and nature of technology change. It is widely reported that improvements in technology are making many types of advertising avoidance (including zapping of live TV) easier for audiences (Wilbur, 2008). The introduction of personal video recorders (PVRs) are thought to increase zapping, as audiences can easily exclude all advertising from their TV viewing. However, research has also shown that while such technologies may aid a viewer’s ability to avoid commercials, they may not have a negative impact on advertising effectiveness (du Plessis, 2007; Siefert et al. 2008; Wilbur, 2008). Research Method Australian TV was chosen for this study because the market conditions are such that the content airing on any one station might have an impact on the way audiences zap to and from others. In Australia, there are just five Free-to-Air (FTA) channels and Pay TV is only available in approximately 25% of households (Rock and Pearse, 2005). Of the FTA channels, only three have substantial share (around 25% average weekly ratings), and one of the remaining channels is commercial free. This is a substantially less complicated market than that in some other countries, where the presence of more channels is expected to generate more zapping (McDonald, 1996) and where Pay TV dominates audience viewing. A less complicated market makes it possible to observe how the programming on one channel may affect the amount of zapping to/from another channel. We used minute-by-minute aggregate ratings data (OzTAM in Australia) to estimate the size of the audience each minute (number of people watching per minute). The OzTAM panel involves households who are recruited to be collectively representative of the Australian population. While this is a national panel, data for just one metropolitan market (Adelaide, with 475 panellists, the behaviour for whom is projected to a population of 1,318,000) was chosen for the analysis. We chose just one market as the programming on each of the stations varies from state to state. We used a week of evening (7:30pm-10:30pm) data from November 2006, which represented a typical viewing period for Australia (i.e. not a peak ratings period or during holidays). The three major FTA commercial channels were analysed. The actual broadcast was matched against the OzTAM data to determine the content of each minute of broadcasting (i.e. advertising or programming content). Commercial break minutes were those that contained any non-programming content. The data for this study included 56 ANZMAC 2009 Page 4 of 8 programs across eight genres and 276 commercial breaks. A break consisted of seven paid commercials on average, with 84% of breaks containing a promotion (either network or program) at the start of the break and 50% airing a promotion at the end of the break. Audience gain for any one minute is defined as the percentage increase in the absolute audience from the previous minute. Loss is the percentage decrease in audience from the previous minute. As such, the gain/loss is not simply the increase/decrease in ratings (TARPs), allowing us to account for any impact that different ratings across programs and networks may have on audience migration. Our paper makes two contributions. We provide descriptive information on audience loss and gain, investigating some of the variables that might be expected to influence such measures given previous research. Secondly, we conduct a time-series analysis to determine how losses and gains relate to what is being broadcast on competing channels. Results and Discussion Table 1 and Table 2 summarise the key audience loss/gain descriptive statistics. Figures represent the average proportional rate of loss/gain in audience (i.e. not TARPs) from the previous minute, across all three channels. Table 1: Descriptive Statistics (Content of Current and Previous Minute) Switching during… Away (%) Programming minutes 3.8 Commercial break minutes 6.1 A program minute when the previous minute was… Programming 3.6 Commercial break 3.2 A commercial minute when the previous minute was… Programming 4.3 Commercial break 6.7 To (%) 4.5 3.4 Net (%) 0.7 -2.7 4.3 6.1 0.7 2.9 3.6 3.41 -0.7 -3.3 Over the week of prime time Australian TV, zapping during programming results in a 0.7% net gain in audience (Table 1). Zapping during commercial breaks produces a net loss of 2.7%. These results provide further support for the TV industry’s move to determine ad space costs based on commercial rather than program ratings. As expected, there is more zapping away during commercial breaks (i.e. 6.1% compared to 3.8%) and switching to a channel is more likely during programming (4.5% c.f. 3.4%). Table 1 also shows that loss is greatest during commercial minutes when the previous minute also contained advertising, at 6.7%. This result indicates that audience loss continues across an ad break. Furthermore, we see that audiences return rapidly after a break (i.e. gains are high when a program minute follows an ad break, at 6.1%). 1 Chi Square tests showed that all differences in average loss/gain rates were statistically significant (p<0.001). Page 5 of 8 ANZMAC 2009 Previous studies have tested various factors for their effect on ad break audience levels. The most common of these are time of the day (McConochie et al. 2005; Siddarth and Chattopadhyay, 1998), program genre/type (Brennan and Syn, 2001; Danaher, 1995; Meurs, 1998; McConochie et al. 2005) and the length of the program (Danaher, 1995; Meurs, 1998). We investigated such variables (Table 2) and found that program genre appears to have an effect on zapping, with comedies and movies loosing more of their audience than dramas. Table 2: Descriptive Statistics (Program Structural Factors) Ad Break Switching Away (%) To (%) Time: Ad Break Switching Away (%) To (%) Program Genre: 7:30-8pm 8:01-8:30pm 5.4 5.6 3.1 3.0 Comedy Movies 7.9 7.8 3.5 4.1 8:31-9pm 6.6 4.4 News/Current Affairs 7.6 4.8 9:01-9:30pm 5.9 3.3 Documentary 7.1 2.3 9:31-10pm 6.5 3.8 Light Entertainment 5.6 3.5 10:01-10:30pm 6.8 3.1 Infotainment/Lifestyle 5.5 3.3 Reality 5.3 3.4 Drama 4.9 2.9 Program length: Less than 60 mins 60 mins 7.3 5.6 3.3 3.3 More than 60 mins 6.9 3.8 To more fully analyse the effects of commercial breaks on all three major stations simultaneously we used a Vector Autoregression Model with exogenous variables (VARX model (see for example Nijs et al. 2001). Minute-by-minute gains and losses for the three stations formed six endogenous variables, and commercial breaks (coded 0,1) for each station formed the exogenous variables. The appropriate lag structure was determined through the Bayesian Information Criterion. A separate model was run for seven individual days of viewing data, and the results were pooled. The results are shown in Table 3. Due to space limitations only the instantaneous effects are reported. Table 3: VARX coefficients. Figures represent audience percentage gain or loss. Gain on Loss/Gain on each Ch 1 channel… → Commercial Break on…↓ Channel 1 -1.0 Channel 2 Channel 3 Loss on Ch 1 Gain on Ch 2 Loss on Ch 2 +1.6 +1.0 -0.5 +2.0 Gain on Ch 3 Loss on Ch 3 -1.1 +1.3 This analysis shows that when channels have an ad break in a particular minute, their rate of audience loss increases by 1.6 % points on average, and their rate of audience gain decreases by about 1.0 % point on average. Adding the reduced gain and the increased loss amounts to a ‘cost’ of 2.5% audience in an ad break, on average. There was only one instance of a crosschannel effect that was consistent across the seven nights, being that when Channel 1 had an ad break, Channel 2 gained an extra point in the same minute. Results support expectations that zapping is more affected by advertising on the focal channel, than by what is being ANZMAC 2009 broadcast on competing stations. Furthermore, results suggest that when audiences switch away from the focal channel during advertising, they are more likely to switch to another channel during programming rather than to another ad break. Conclusions and Future Research Our findings firstly show that zapping of prime time Australian TV commercial breaks is not common, accounting for only a 2.5% loss in audience on average from the previous minute. This is in line with Danaher’s (1995) finding of a 5% reduction in TARPs for New Zealand television during commercial breaks. Given that much of the previous work in this area was conducted more than a decade ago, the introduction of new technology that makes zapping easier, seemingly has had a limited impact on the propensity for audiences to zap live TV. Unlike many previous studies in this area, we have highlighted that audiences zap not only during commercials, but also during programs, showing that zapping behaviour is not unique to commercial breaks. In addition, we highlight that audience losses are often counteracted by gains. While Meurs (1998) also reports this effect during ad breaks, his loss and gain figures are considerably higher than those reported here (net loss of 21.5% compared to 2.5%), which is potentially due to significant differences between the studies in the measures used. Furthermore, we show that audiences who zap return to programs within minutes of a commercial break ending, supporting Danaher’s (1995) contention that audiences become accustomed to ad break length. If zapping is to occur, it will occur regardless of the environment in which the ad sits. The implications for networks and advertisers are that ads placed in certain environments are not likely to suffer greater audience loss as a result. In relation to cross-channel programming, we find that while commercial breaks on one station increase the rate of audience loss for that channel, that this does not necessarily result in gains for other stations, depending upon what those other channels are broadcasting. In an uncomplicated market (like Australia), when one channel loses viewers during an ad break, advertisers on competing networks do not appear to gain from their loss. While this study has shown that zapping is relatively uncommon, advertisers must also take into account the magnitude and effect of other avoidance behaviours such as turning the sound down/off or leaving the room. In addition, the current study investigated a limited number of factors for their effect on ad break zapping which did not include, for example, characteristics of the commercials themselves (Siddarth and Chattopadhyay, 1998; Meurs, 1998), or characteristics of the viewers (Danaher, 1995; Rojas-Méndez, Davies and Madran, 2008). Analysing more markets and comparing results across studies could also extend the current research. A limitation of the minute-by-minute data used is that audience gain and loss rates include not just channel switching, but also some element of switching the television on or off, which may inflate or deflate zapping levels. In addition, the data may contain overlap between programming and advertising content in the first and last minutes of ad breaks, and in the first program minute after a break. Future research should, where possible, investigate audience zapping behaviour with second-by-second data. This more granular data will enable researchers to investigate channel switching at the individual advertisement level, and to separate programming from advertising content at the beginning and end of commercial breaks. Page 6 of 8 Page 7 of 8 ANZMAC 2009 References Atkinson, C., 2008. How commercial ratings changed the $70B TV market: commercial ratings white paper. Advertising Age, October, 1-12. Brennan, M., Syn, M., 2001. Television viewing behaviour during commercial breaks. Proceedings of the Australian and New Zealand Marketing Academy Conference. Albany, New Zealand, CD-ROM. Danaher, P., 1995. What happens to television ratings during commercial breaks? Journal of Advertising Research 35 (1), 37-47. du Plessis, E., 2007. DVRs, fast forwarding and advertising attention. Admap, September, 4851. Green, A., 2007. Understanding the T viewer. World Advertising Research Centre, Best Practice, November. James, L., 2009. WFA global advertising and economic data 2007-2008 and outlook for 2009. World Advertising Research Centre, Online Exclusive, March. Kaplan, B., 1985. Zapping - the real issue is communication. Journal of Advertising Research 25 (2), 9-12. Kwak, H., Andras, T.L., Zinkhan, G.M., 2009. Advertising to ‘active’ viewers. International Journal of Advertising 28 (1), 49-75. McConochie, R., Wood, L., Uyenco, B., Heider, C., 2005. Progress towards media mix accountability: portable PeopleMeters' (PPM™) preview of commercial audience results. ESOMAR TV Conference. Montreal, June, 1-17. McDonald, C., 1996. Zapping and zipping. Admap, January, 1-3. Meurs, L.V.,1998. Zap! A study on switching behavior during commercial breaks. Journal of Advertising Research, Jan/Feb, 43-53. Nijs, V.R., Dekimpe, M.G., Steenkamp, J., Hanssens, D.M., 2001. The category-demand effects of price promotions. Marketing Science 20 (1), 1-22. Rock, B., Pearse, S., 2005. Is this remote stuck or what? Network loyal, programme loyal, or both? ESOMAR, Cross Media/Television Conference. Montreal, June. Rojas-Méndez, J,. Davies, G., Madran, C., 2008. Universal differences in advertising avoidance behavior: a cross-cultural study. Journal of Business Research 62, 947-954. Siddarth, S., Chattopadhyay, A., 1998. To zap or not to zap: a study of the determinants of channel switching during commercials. Marketing Science 17 (2), 124-138. Siefert, C., Gallent, J., Jacobs., Levine, B., Stripp, H., Marci, C., 2008. Biometric and eyetracking insights into the efficiency of information processing of television advertising during fast-forward viewing. International Journal of Advertising 27 (3), 425-446. ANZMAC 2009 Wilbur, K., 2008. How the digital video recorder (DVR) changes traditional television advertising. Journal of Advertising 37 (1) Spring, 143-149. Page 8 of 8