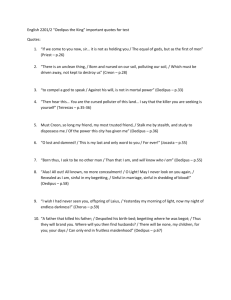

Oedipus Rex Sophocles

advertisement

Oedipus Rex Name: Study Guide Sophocles Initial Considerations ! Oedipus is a great celebrity, a national leader of a city-state at a moment of crisis. Thebes has been mysteriously attacked by the plague, something which both Oedipus and the citizen see as a manifestation of the fatal forces of the universe in which they live. The citizens are dying, and they want, if possible, to stop the disaster. The future of their city depends upon that. They naturally turn to Oedipus, their firm and popular ruler. Prologue The opening of the play makes at least two things clear. First, the citizens have enormous respect, even love, for Oedipus. They acknowledge not only his political power (which they have given him), but also his pre-eminence among all human beings for wisdom, especially in dealing with things they don't understand: "We judge you/ the first of men in what happens in this life/and in our interactions with the gods" (37-39). Second, we see in Oedipus a person of enormous self-assurance and self-confidence, a man who is willing to take on full responsibility for dealing with the crisis, a task which he clearly accepts as his own unique challenge. Oedipus has, we observe right from the opening lines, an enormously powerful sense of his own excellence, of his own worth (the most obvious indication of this point, something worth attending to throughout the entire play, is the frequency of the pronouns I and me in all of Oedipus's utterances). ! The opening also makes clear to us that both the chorus's confidence in Oedipus and his strong sense of his own worth derive from past experience. Oedipus has saved the city before, at a time when many others had tried. And he did it with his mind, his intellect: he solved the riddle of the Sphinx. So the opening speeches clearly establish a harmonious relationship between ruler and ruled, based on past experience. Oedipus's confidence is not, in other words, merely an illusion. He has an exemplary record, the people have come to him because of that quality, and he fully intends to live up to that standard. Yes, he has a high regard for himself, but we are given to understand that that is quite deserved and shared by those over whom he rules. ! His first steps to deal with the crisis, that is, to send to the oracle for some instructions, are entirely appropriate. Given that fate has brought on the plague, what can fate reveal about its origins? Oedipus has, in fact, anticipated the request of the priest: he has already acted on his own initiative to address the crisis. And when the oracle's report is made public, Oedipus immediately and forcefully proclaims his famous curse against the murderer of Laius, the previous king. All this seems very appropriate. And, in fact, it does serve to reassure the people. Their fears are calmed, because Oedipus, their king who saved them before, is taking care of the problem. ! At the same time, however, this scene gives us our first sense of what becomes inescapable later on. Oedipus, in accepting the responsibility, has no room for sharing the problem with anyone else. As a measure of his own greatness, he will resolve Thebes's distress, and he will do it openly for all to see. That's why he can dismiss Creon's suggestion that he listen to the report about the oracle privately first and why he can confidently declare "Then I will start afresh, and once again/ shed light on darkness" (159). He is taking on the task as a personal challenge, to be dealt with in his terms, not by delegating it to someone else or, indeed, by discussing the matter with others or, as we shall see, by listening to what others have to say and acting on their suggestions. Points to consider: 1. Identify at least three examples/instances of irony in the Prologue (any one of three forms): 2. List one example for each of the following: Oedipus as fatherly: Oedipus as sympathetic: Oedipus as smart: Oedipus as proud: • Oedipus as paranoid: PARODOS ! There's a plague on the land of Thebes, almost certainly a dramatic reflection of the terrible disease which had recently struck Athens. The sight of the Chorus begging their gods and rulers for help must surely have been a painfully vivid memory for the Athenians. One reason, then, that Sophocles has added the plague to the Oedipus legend is, no doubt, because of the currency it held for his audience. How he intends to integrate the epidemic into the legend is, however, still unclear at this moment in the play. 3. The chorus often comments on the action, reinforces a point of view, or interprets the action—how is it functioning in the Parados? SCENE I The most obvious indication of Oedipus's total commitment to himself is the famous quarrel with Teiresias. To some readers Oedipus's conduct here seems very odd, but this quarrel makes perfect sense if we see Oedipus as someone with no sense of ambiguity in life, as a person wedded to the view that his conception of what matters is, in fact, the truth. By that standard, Oedipus has good reason to be angry with Teiresias and to suspect him. For Teiresias knows the murderer of Laius and will not tell. Oedipus has absolutely no sense that he might be involved at all. And since he has no conception of that as a possibility, it cannot be true. Thus, when Teiresias announces to Oedipus that "the accursed polluter of this land is you" (421), Oedipus's interpretation is clear enough: Teiresias must be lying, and he must have a reason, a secret agenda. A different man might well stop at this point, calm down, and ask Teiresias what he meant. But Oedipus is not that sort of person. In fact, rather than listen to Teiresias, Oedipus reminds everyone of his previous triumph over the Sphinx (stressing that Teiresias failed to help Thebes then)—he derives a sense of what is right from who he is based on his past achievements, rather than from any more flexible appreciation for more complex possibilities. 1. Teiresias says that knowledge can be “dreadful.” In what ways is he right? 2. In Ode I, how do the people feel about the dispute between Oedipus(their king) and Teiresias (their spiritual leader/adviser)? Examples of Irony in Scene I: References to blindness/sight in Scene I: SCENE II ! ! Oedipus's treatment of Teiresias and Creon concerns the Chorus, and they make some attempt to calm things down, recognizing that Oedipus's quick judgment may be leading him to misjudge what Creon and Teiresias are saying. But they will not abandon or criticize Oedipus because they understand that if some decisive action needs to be taken, he's the only one who can do it. They certainly cannot expect Creon to tackle the problem head on. After all, he makes it clear to everyone (including the readers) that he's primarily a cautious political operator, happy to play that game as second fiddle, with no desire to manifest his own excellence to the full. ! ! Jocasta clearly wants the whole matter just to go away. She has precisely the wrong advice for Oedipus (not that he would listen to anyone's advice anyway) when she advises him to cease his investigation into his fate because there's no such thing, inviting him to live his life for the moment. What she's doing here, of course, is inviting Oedipus to be someone else, someone who has no concern for living up to his reputation for knowledge and courage. And, of course, Oedipus doesn't listen to her, just as he doesn't listen to anyone else. One needs to measure Oedipus's stature against the other characters in the play, taking into account his capacity for decisive action in comparison to their inaction or unwillingness to think through the need for action. Whatever one might like to say by way of criticizing Oedipus, that point remains. 1. What common pattern of behavior does Oedipus exhibit in his dealings with Lauis, Teiresias, and Creon? 2. What is Jocastaʼs attitude toward the oracles throughout this scene? 3. What is the Chorusʼ reaction to Jocastaʼs attitude in Ode II? Examples of Irony in Scene II: References to blindness/sight in Scene II: SCENE III ! Note Jocasta's silence as Oedipus interrogates the Corinthian messenger about the rescue of baby Oedipus on Cithaeron. This is an excellent example of how reading a dramatic text is no substitute for seeing the play performed on stage. As Oedipus pumps the messenger for information, he does not realize the full impact of what he is saying because he does not know the details of his exposure as a baby on the mountain. But Jocasta does! If this were a movie, the camera would focus not on the characters who are speaking (Oedipus and the messenger) but Jocasta who says nothing and at the same time is the only person in the scene who knows what's really going on. Her silence is a deafening scream of pain. ! It seems clear that Sophocles has composed the drama with the idea that the majority of his audience understands Oedipus is Jocasta's son. For those in the know this scene oozes with irony and double meaning, but for those who are not aware of this, it constitutes equally effective theatre. A friend of mine once attended a production of Oedipus and sat in front of a woman who about midway through this scene gasped, turned to her companion and said, "Oh my god, she's his mother!" Clearly the scene works quite well for the uninitiated, making it hard to believe Sophocles did not have both sorts of viewer in mind when he wrote the play. 1. How do both Jocasta and Oedipus act irreverently toward oracles in the first part of this scene? 2. How does Jocastaʼs attitude change once she has been “enlightened”? How does Oedipus misinterpret her attitude? 3. Examine Ode III and explain the chorusʼ attitude toward the unfolding drama. Examples of Irony in Scene III: SCENE IV The climax of the play comes swiftly and mercilessly as Oedipus joins Jocasta in realizing their true relationship. When he roughs up the old herdsman in violent determination to learn the truth, Sophocles shows us again the Oedipus who murdered Laius in the heat of anger, the same angry man who threatened the blind Teiresias earlier in the play. It is important to understand the sympathetic tone of the fourth choral ode. It sets the audience up for several responses: 1. It suggests that Oedipus is innocent of knowingly murdering his father and marrying his mother. 2. It offers the hope that the gods will intervene and save Oedipus from punishment. 3. It prepares the audience to pity Oedipus in his final entrance as a ruined hero. 4. It allows the audience to judge for themselves if Oedipus' decision to blind himself is just payment for his actions. 1. How does Sophocles generate a feeling of climactic action in Scene IV? 2. How does the chorus expand on the theme of illusion and reality in Ode IV? EXODOS ! The Second Messenger's report describing Jocasta's suicide and Oedipus' self-blinding and the ensuing scenes of grief and despair which conclude the tragedy will seem over-drawn to many of us who are used to a brief denouement after the climactic scene of a play. But the Greeks evidently relished more tortuous, if not torturous finales. From the number of protracted scenes involving wailing and mourning that cap ancient dramas, it seems safe to gather that Athenian audiences in antiquity enjoyed a good communal cry. Oedipus explains the rationale behind his self-blinding: "I do not know with what eyes I could look upon my father when I die and go under the earth, nor yet my wretched mother—those two to whom I have done things deserving worse punishment than hanging." The ancients believed that people entered death in the condition they left life. So, if Oedipus were blind at death, he would be blind in the underworld, too. Thus, he wouldn't have to look upon the parents he's harmed so horribly. Some today interpret Oedipus' blindness as a metaphor for the recent death of Pericles, Athens' greatest democratic leader, a victim of the plague which first struck the city in 430 BCE. If so, Sophocles seems to be saying that the loss of Pericles has blinded Athens which, like Oedipus, is now doomed to wander aimlessly in the dark. 1. What does Oedipus sense about his destiny? 2. What image of Creon is left by his final words to Oedipus?