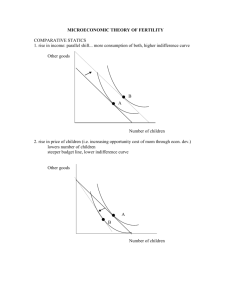

Consumer Sovereignty

advertisement