Chapter TwentyFour. Judaism from the Arabian Conquests to the

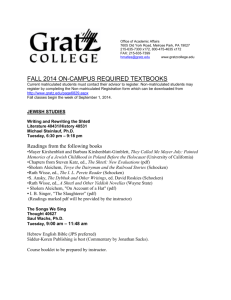

advertisement