Interest groups and international economic cooperation: the role of

advertisement

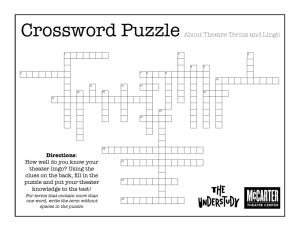

Interest groups and international economic cooperation: the role of ideas A case study of services liberalization Hans Diels Department of Political Science University of Antwerp hans.diels@ua.ac.be Paper Prepared for the Workshop “International Political Economy”, at the Dutch/Flemish Politicologenetmaal 2010, 27-28 May, Leuven, Belgium (Work in progress, please do not quote without author‟s permission) Does the involvement of interest groups facilitates international economic cooperation between states or does it erect new barriers? Most approaches aiming to answer this question start by conceptualizing international negotiations as a two-level game where at one level, the negotiators bargain with each other and at the other level bargain with domestic and foreign interest groups (Putnam, 1988). Negotiators and domestic actors can interact with other actors and try to use the two-level structure at their advantage, by using one level to get leverage over another level. Moravcsik‟s liberal intergovernmentalism builds further on this framework (Moravcsik, 1997; 1998). This model is very useful for understanding how interest groups have an effect on the cooperation between states when the preferences of societal actors and negotiators are fixed, but often this assumption is contrary to reality and should be loosened. There‟s more than bargaining in the interaction between governments and between interest groups and governments. Actors can also use new ideas to change the beliefs the other actors hold. When starting from preferences that can change, the bargaining interactions between the negotiators and domestic interests only capture a small part of the interaction process and should be complemented with a mechanism that explains how, in interaction with each other, these actors may adapt their preferences. Actors can try to persuade other actors, using rhetorical action (Schimmelfennig, 2001) or can try together to get a better understanding of the situation, this is called deliberation (Elster, 1995), both are based on a logic of arguing instead of bargaining (Habermas, 1984; see also Risse, 2000b). Students of the role of transnational movements in spreading norms internationally, are much more comfortable with this logic of arguing (see e.g. Keck et al., 1998; Risse-Kappen et al., 1999). They developed models of how ideational factors influence the preference formation of states. But how ideas are used by interest groups to influence the outcome of international economic relations has been left understudied.1 The effects of arguing can be direct and indirect. Actors can directly convince other actors to adapt their preferences, but they can also influence actors, who then influence other actors. Authors writing on Daugbjerg (2008) studied how ideas were the subject of negotiations in a two-level game but did not analyze how ideas were used in the 2LG. 1 1 human rights norms have already studied how indirect influence of ideas, in their case more specific principled ideas or norms, can affect state actors‟ preferences through a “boomerang (Keck & Sikkink, 1998)” effect or a “spiral model (Risse et al., 1999),” but in the field of international negotiations and economic policymaking these indirect effects have been neglected. I will call this indirect influence through arguing, ideational reverberation. When preferences change the potential for cooperation will change. When actors share an understanding of the causal mechanisms driving a specific issue, they will find it easier to conclude an agreement than when they disagree on how something works. This implies that whether the potential for cooperation would change, depends on which actors adopt the new ideas. In this paper I argue that new ideas2 can change the level of cooperation between states. I claim that the variation in the effects of ideas on cooperation has to be explained in three steps. First, the interaction between actors‟ belief systems, psychological characteristics and the external environment explains variation in why and when existing beliefs are discarded. Second, factors concerning the congruence between new ideas and existing beliefs, concerning the actor promoting the idea and concerning other actors adopting the idea, will explain why some ideas are adopted while others are neglected. Third, the constellation of actors who adopt and neglect the new idea will influence the effect of the idea on cooperation between states. This paper will first discuss how the adoption of new ideas can influence cooperation between states. Then the paper deals with why existing beliefs are discarded. Third is a discussion on why some new ideas are incorporated in actors‟ belief systems while others are neglected. Fourth, I will discuss the mechanism that accounts for the spread of ideas, indirectly influencing new actors. The fifth part consists of a first test of the theory on the case of cooperation on services liberalization. Finally, I‟ll resume the core elements of my argument in the conclusion. Effects on interstate cooperation In a bargaining two-level game, interest groups determine the potential for intergovernmental cooperation by influencing the bargaining space. The bargaining space is the part where the different negotiators‟ winsets overlap, it contains the range of agreements for which all negotiators can find political support. In the case of arguing, how and whether new ideas change the negotiation process will depend on who adopts the new ideas. First of all a new idea does not have to be adopted by any actor to be influential in the negotiation process. New ideas can lead to a process of „creative destruction,‟3 where new ideas are used to delegitimize existing beliefs. This process can later on lead to the adoption of these new ideas, but it is also possible that the new ideas succeed in destroying the credibility of existing beliefs without I will use the term beliefs when referring to ideas that are incorporated in an actor‟s belief system and ideas when talking about ideas that are „still out there‟. 3 Schumpeter (1943), building on the works of Karl Marx popularized this idea in economics. 2 2 succeeding in replacing them with new ideas in the actors‟ belief systems. In these situations the introduction of new ideas leads to more uncertainty in international negotiations, making it more difficult for the negotiators to reach agreement. Second, in situations where ideas are successful in the destruction of existing beliefs and are able to convince actors of their value, becoming enshrined in their belief systems, the effect on the negotiation process will depend on whether all actors or only one adopts the new idea. If only one actor adopts this new idea and the other remains uncertain after the creative destruction of her existing beliefs, one-sided uncertainty results. If one actor adopts the new idea while the other keeps his pre-existing beliefs, the two actors will negotiate based on different analytical frameworks. In both cases the negotiations will become more difficult. Figure 1: Variation in the effect of new ideas on cooperation between states Only in a situation where both actors adopt the new idea, albeit in a modified form, common knowledge will be created and this has the potential to facilitate the negotiation process. When all actors have determined their preferences, the uncertainty has decreased, then both intergovernmental negotiations and government-society negotiations will return from a logic of arguing to bargaining. But of course the preceding arguing may have changed the preferences and may cause important changes in the potential societal coalitions that can be concluded and therefore on the win-sets of the negotiators and the preference configurations of the negotiators. Common knowledge creation can change the strategic interaction between negotiators. It can “alter the payoff structures” of the negotiators and changing the “relative appeal of the best alternative to a negotiated agreement” (Culpepper, 2008, p. 9). This can happen for two reasons. First the new knowledge can lead to a re-evaluation of one‟s own interest in the new framework. Second, the fact that the other negotiator has a new view of how things work, can lead the first negotiator to be more willing to follow a specific solution. By creating common knowledge the behavioral options of negotiators are narrowed down, because they are normatively unacceptable (Schimmelfennig, 2001) or are technically unfeasible. 3 When actors negotiate on economic issues, it becomes very difficult to reach an agreement when they have totally different causal beliefs about how the economy works. When one actor strongly beliefs in Keynsian economics while the other is convinced that a monetarist approach explains reality, it will be very difficult to find ways to cooperate on economic policymaking. For example, it was only when a neoliberal policy consensus emerged in Europe that agreement on monetary integration became possible (McNamara, 1998; 1999). While a basic shared understanding of how things work is important for reaching agreement, actors can still differ widely on what goals they will pursue. For example, French parties on the left and on the right share a certain vocabulary and analysis concerning supporting supranational institutions but have quite different values concerning its ends (Parsons, 2003). Actors need to find a common definition of the situation before they can discuss the different solutions (Risse, 2000a; Culpepper, 2008). On many issues there may exist shared basic understanding on the issue, especially on issues that have been on the table for a long time. However, on new issues, there will be less shared understanding and common knowledge will have to be established before negotiations on the issue can really begin. But also on older issues, common knowledge can become questioned in situations of crisis, with international or domestic origins (Acharya, 2004) or when new ideas attack existing beliefs (Blyth, 2001). The role of how common knowledge influences international cooperation has been analysed in the study of epistemic communities. In the field of international security, Adler discussed how the epistemic community was able to spread shared “reasons why [...] it was important that they cooperate” (Adler, 1992). On epistemic communities in general, Adler and Haas described how “National policymakers can absorb new meanings and interpretations of reality, as generated in intellectual, bureaucratic, and political institutions, and therefore can change their interests and adjust their willingness to consider new courses of action (Adler et al., 1992).” In the field of economic cooperation, John Ikenberry‟s (1992) study of the Anglo-American postwar settlement shows how experts influenced negotiations by “crystallizing areas of common interest between the two governments.” Gourevitch (1989) showed how Keynesian ideas saw “the potential for a collective game.” And Hirschman (1989) wrote in his comments in the same book: “Here is an excellent example of how a new economic idea can affect political history: it can supply an entirely new common ground for positions between which there existed previously no middle ground whatever.” On monetary coordination, Kathleen McNamara (1998; 1999) showed how in addition to structural factors, shared normative and causal ideas were essential to explain why states cooperated on monetary cooperation. My approach adds to this epistemic community approach a model explaining the different steps that cause variation in the effect that new ideas can have on cooperation. And my approach also emphasizes how the influence of new ideas can vary, not only facilitating cooperation but also throwing up new barriers. 4 This leads us to three hypotheses concerning the influence of new ideas on cooperation between states. First, when ideational entrepreneurs are able to create common knowledge between the different actors in a two-level game, the probability of a successful conclusion of the negotiations becomes bigger. Second, in situations where the new ideas only succeed in discrediting the existing beliefs or where only one negotiator changes her beliefs, uncertainty or analytical differences will make negotiations more difficult to conclude. Destructing existing beliefs After explaining the effects ideas can have on the potential for cooperation between states, I will explain the different steps that have to be taken for an idea to have a causal influence on interstate cooperation. In this section I explain how beliefs can get destructed and replaced by new ideas. Whether existing beliefs will be destructed depends on an interaction process between the information an actor receives about his environment, his current belief system and the psychological construction of people‟s brains. Actors tend to update their beliefs very slowly and build further on their existing beliefs (Tetlock, 1991), Tversky and Kahneman (1974) call this the „anchoring and adjustment‟ heuristic. As a consequence the beliefs actors have are very sticky and will only be adapted when new information about the world around them is too discrepant with their beliefs and comes all at once (Levy, 2003). Discrediting beliefs can be caused by a crisis demonstrating the failure of the existing causal ideas or can arise when an actors‟ beliefs are attacked by competing ideas (Hall, 1993; Blyth, 2001; Acharya, 2004). Crises can be domestic or international (Acharya, 2004), resulting from the failure of one policy paradigm and the success of another (Hall, 1993) or can arise because the beliefs of actors are attacked by new ideas that question existing beliefs (Blyth, 2001). Actors will only adopt their beliefs when the incongruence with reality is too high to ignore, before this point, beliefs will remain very „sticky.‟ A paradigm or theory will only be considered false when there‟s a found a new one “that is definitively better” (Boudon, 2003, p. 16). Thus for beliefs to become discredited, the stickiness of beliefs can be overcome by providing enough information demonstrating the discrepancy between the actors‟ beliefs and the environmental reality. Creating new beliefs When existing beliefs are discarded, actors will search for new ideas. They will learn these new ideas from other actors, societal actors or other governments. Building on Habermas‟ „Theory of communicative action,‟ authors like Risse (2000b), Naurin (2010) and Müller (2004) have been claiming that there‟s another logic than bargaining governing social interactions, „arguing.‟ There are two ways of communication when actors try to find an agreement. An actor can use threats and promises to convince other actors to sign the agreement she wants, this is bargaining. But she can also try to persuade the other actor with rational arguments, try to change her preference ordering, this is arguing. An important difference between bargaining and arguing is the claim actors make. In the case of bargaining negotiators make a claim to the credibility of their threats and promises. When the other actors don‟t believe that you 5 will be willing or be able to carry out your threats or promises they won‟t let themselves be influenced by them (Schelling, 1960). When arguing, actors make claims to validity, they want the other actor to understand their point of view. We talk about deliberation when all actors are open to be persuaded, when all actors are potential receivers and senders of new factual or normative information. In situations of rhetorical action, there‟s one sender, trying to persuade a receiver of her point of view.4 Which ideas will be incorporated in actors‟ belief system depends on their claims to validity. According to Habermas (1984, p. 50) there are three validity claims: “propositional truth, normative rightness, and expressive sincerity.” „Propositional truth‟ refers to “the conformity with perceived facts in the world” (Risse, 2000b, p. 9), factual validity. Normative rightness is about whether the claims fits with existing higher-order norms (see also Muller, 2004). This implies two things. First, new ideas will have to be congruent with the new information that discarded the old ideas in the first place. They must be able to solve the cognitive puzzle that was created (Culpepper, 2008). This claim will be supported when the new idea has strong information about its viability (Simmons et al., 2004), can claim some cases of successful implementation (McNamara, 1999; Acharya, 2004). Second, new ideas should also fit with the other causal and normative beliefs the actors have. (Risse-Kappen, 1994; Woods, 1995; Hansen et al., 2001). The more compatible they are with the existing belief system of an actor, the higher their chance on success (George, 1980; Levy, 2003). Partially these deeply engrained beliefs are determined by the prevailing culture in a state, there should be a match between the new ideas and the existing culture (Benford et al., 2000; see also Acharya, 2004), there is also a more fluent factor to this match, this is what Campbell (1998) names the „public mood.‟ In addition, the message should be simple, clear, coherent and not too complex (Risse-Kappen, 1994; Woods, 1995; Campbell, 1998). Ideas are used to reduce uncertainty and therefore too complex ideas, just don‟t work as they don‟t reduce uncertainty enough. It will also be easier to launch new ideas that only require an adaptation of the current structure than ideas that require completely new structures (Parsons, 2003; Acharya, 2004). „Expressive sincerity‟ refers to whether the author of the claim means what he says. Only ideas that are proposed by actors that are trusted will matter. Ideas are not just out there, they have to reach people to be able to change their beliefs. Therefore to promote a new idea, you need access to those people you try to convince. As Truman said “the power of any kind cannot be reached by a political interest group, or its leaders, without access to one or more key points of decision in the government (Truman, 1951, p. 264).” This implies that actors promoting ideas will need a minimum of access to be able to make their case. Ideas also become politically influential in part because they interact with powerful institutional forces and political actors (Hall, 1993; Hansen & King, 2001; Béland, 2009). This does not imply that ideas don‟t Negotiators can also use strategically impartial arguments that are disguises for their partial goals, or substitute truth claims for credibility claims. This can be done by communicating a warning instead of a threat. A threat is something that the speaker promises to do whenever he doesn‟t get what he wants. A warning is communicating about „something that will happen,‟ but is out of the control of the actor, whenever a certain choice of action is made (Elster, 1995). 4 6 have an independent effect from the power of the actors supporting the idea5. Being supported by an actor who has a minimum of access to other actors is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the success of an idea. This is linked to what Habermas (1984, p. 50) named „expressive sincerity,‟ for an idea to be successful the actor expressing the idea needs to be credible and to be credible it will be important to have a good reputation. Ideas coming from an obscure new actor will find it much more difficult to become accepted then ideas promoted by actors with a well established reputation. The probability of adopting a new idea will also be influenced by who else adopts it. When an idea comes up with the above described characteristics it can “crowd out” other ideas by building a “bandwagon” behind it (Culpepper, 2008, pp. 8-9). Finnemore and Sikkink (1998) describe this as a “life cycle of norms” where after a certain number of actors adopts the idea, reaching a “tipping point”, it will become further widespread. Indirect influence: a model of reverberation Above, I argued that the interaction between the different actors in a two-level game is not only determined by a logic of bargaining but also by a logic arguing. In this part, I will go further and show that when actor A convinces B, this can also have an influence on actor C when B argues with C. In this way A has indirect influence on C. In the „classical‟ two-level game, bargaining between actors at level I also influences the bargaining between other actors at level II. When a negotiator finds it difficult to get an agreement ratified at the domestic level, this can, under certain conditions become a bargaining asset at the international level (see Schelling, 1960; Milner et al., 1997; Tarar, 2001; Meunier, 2005), negotiators can collude, try to change their adversaries‟ win-set and domestic constituencies can construct transnational alliances (Evans et al., 1993). When we study the role of arguing in international negotiations, we will also discover that arguing at one level will be able to influence the interactions at other levels. In this section I develop a model to demonstrate that in addition to direct effects, also ideational entrepreneurs‟ actions may have indirect effects (see figure 2). For analytical reason I distinguish three stages in this process. In reality there will not always be a clear distinction between the stages, nor will there be a clear timely demarcation between them. In the first stage the interest group entrepreneur is the central actor who uses a set of ideas to try to persuade negotiators and tries to mobilize other societal interests to support her ideas. In the second stage, the role of the ideational entrepreneur is diminished as the ideas travels further when other domestic interests, who changed their preferences after the first stage, start persuading their governments of the merits of the ideas, when negotiators, who were convinced in the first stage, try to persuade their international counterparts of how the idea can be used to solve their shared problems and when societal interests start mobilizing their international counterparts. To avoid tautological reasoning where the ideas they promote may be the resource of the power of an actor I want to point out that I am referring to the power actors have before they start promoting the idea. 5 7 As the idea is no longer handled by one single actor, the interest group entrepreneur, the idea will start to modify as aspects of it will be adapted to other actors‟ existing beliefs. This is the third phase of ideational feedback. After these three stages, the fog of uncertainty disappears over the negotiations and the actors return to a logic of bargaining, but now based on their potentially changed preferences. These three stages are analytical constructs and are not linked to different phases following each other in reality. In fact these stages will occur together. Figure 2: Ideational reverberation Stage 1: Entrepreneur at work: direct ideational influence In the first stage the central actor is the interest-group entrepreneur who will try to persuade governments and mobilize societal interests with his set of ideas. I call the influencing of the government with ideas „ideational lobbying‟. When governments are confronted with situations of analytical uncertainty, they will start a search for more information and ideas. Interest groups can provide these ideas. This is demonstrated in the literature on how lobbyists provide technical information to governments (on expertise-lobbying see e.g. Truman, 1951; Pappi et al., 1999; Bouwen, 2004). But interest groups can also use ideas to mobilize other societal interest. The literature on transnational movements distinguishes two aspects to this framing, “consensus mobilization” and “action mobilization” (Klandermans, 1984). I will talk about consensus mobilization when discussing ideational feedback. Action mobilization means getting people from the “balcony to the barricades (Benford & Snow, 2000, p. 615),” getting them to engage in the political battle for the ideas at stake. This is done by persuading them to change their preferences and/or letting them act to defend their preferences. When successful the target societal actors will learn from the entrepreneur and adapt their preferences (for an example of firms learning from each other see Martin, 1995). 8 Stage 2: Idea on the run: indirect ideational influence In the second stage, the interest group is no longer the central actor, as other actors will start spreading the idea. Newly convinced domestic actors can convince their domestic or international counterparts or their government, this happens through the same mechanisms as described in stage one. But there are two other mechanisms. When one of the governments has clarified her preferences she can start to try to persuade other governments who are still uncertain about their preferences and need to clarify their beliefs. This happens through rhetorical action (Schimmelfennig, 2001) and can result in intergovernmental learning. Once governments have clarified their own preferences, they can start to mobilize societal interests to find support for her position. In this stage they will do this by trying to persuade societal actors of the new ideas, in this way changing their preferences (on how governments mobilize private interests to defend their own position see e.g. Martin, 1991; Van den Hoven, 2002; Woll, 2009). Stage 3: The idea returns: ideational feedback As the idea is incorporated in the belief systems of other actors, it becomes more and more an intersubjectively held belief. This implies that the original entrepreneur will not be able to control the composition of the set of ideas as it‟s no longer his idea but an idea of the community sharing the idea. To spread the idea, the idea will have to be adapted to fit with the existing belief systems of other state (Acharya, 2004) and societal actors. This model of ideational reverberation leads us to two hypotheses. First, in situations of uncertainty, arguing between governments and between governments and interest groups will be more important in the beginning of the cooperation process and will be subsumed by bargaining when actors get a better view on their preferences, when the uncertainty is reduced. Second, interest group ideational entrepreneurs are especially important in the first stages of the process, putting issues on the agenda, mobilizing other groups, planting the first seeds at the government level. Their importance dwindles when the process of indirect mobilization starts and becomes even less when the real intergovernmental negotiations start. The further the process moves, the lesser the control of the interest-group entrepreneur on the framing of the idea. 2. Interest groups and the liberalization of trade in services In this section I will describe the process of direct and indirect ideational influence in the process leading to international cooperation on the liberalization of services trade. I will structure my case using the three stages I described in my model of ideational reverberation, in each stage identifying whether, which and how actors beliefs were discredited, and new ideas were incorporated in their belief systems and how all this influenced the cooperation process between states. 9 In September 1986 GATT members gathered in Punta del Este and declared that the new negotiation round would consist of two parts, a first on goods and a second on the liberalization of trade in services. In 1994 the GATS agreement was signed after a trade round of eight years. But the actual negotiations were only a very small part of the process resulting in the liberalization of services. It was neither the beginning nor the end of the liberalization of services. The process started in the 1970s when some US services companies picked up the idea of framing services transactions as trade and took this to the US government, who adopted this idea and started promoting it internationally, resulting in the GATS agreement, and becoming the framework of future negotiations on specific services, like basic telecommunications, financial services, …. In this section I will not tell the story of the negotiations leading to the liberalization of services, but I will explain how a small group of US business actors used the idea of services liberalization to promote their own interests and made cooperation between states on services transactions possible. The idea The idea of seeing services transactions as trade that could be liberalized had its origin in a London-based think tank, the Trade Policy Research Center (TPRC) and the OECD-administration. The TPRC commissioned Brian Griffiths to undertake a study of international services transactions and the barriers these transaction were facing (Griffiths, 1975). Around the same period, a High Level Group on Trade and Related Problems was set up under the auspices of the OECD and under the leadership of Jean Rey, a former European Commission President, to create an intellectual framework for the then forthcoming Tokyo round negotiations. Their report identified barriers to services transactions that are comparable to those barring trade in goods and argued to avoid protectionism in this new important sector of international transactions (Feketekuty, 1988). Before the 1970‟s, services were considered as something that fell strongly under domestic regulation and weren‟t considered as something that was traded. Services were invisible and it wasn‟t always clear what was included under the term „services.‟ But through technological and market evolutions, the market in services was rapidly expanding, making services more important in the economy (figure 3 illustrates the massive growth of services trade between 1980 and 2009. This new evolution was undermining the existing body of regulatory theory, that was “arguing against open entry into services industry” (Drake et al., 1992, p. 56). This evolution started to discredit existing ideas on services transactions and thus created uncertainty over the applicability of the existing concepts in actors‟ beliefs. 10 Figure 3: Worldwide services exports 1980-2009 3500000 3000000 2500000 2000000 1500000 Exports 1000000 500000 0 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2009 Source: WTO statistics database (millions of US dollars in 2009 prices) While the role of services in the economy was growing, there was not a lot of information about international services transactions and their potential in case of liberalization. This information about the new evolutions in the market was important in discrediting the existing beliefs about services. Only by demonstrating the growing importance of services in the economy would it be possible to demonstrate that the existing analytic framework was no longer useful for analyzing services transactions. The idea of the services liberalization as it was promoted by US businesses links two elements, a causal mechanism and a norm. It links the idea that international trade in services can be explained by neoclassical trade theory6 and that therefore liberalizing trade in services would increase global welfare. This implied a “revolution in social ontology.” Adopting this idea would completely change how governments “thought about the nature of services, their movement across borders, their roles in society, and the objectives and principles according to which they should be governed (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 38).” Before, services were seen as something that had to be regulated at a domestic level. The ideational entrepreneur The idea was picked up by US services companies who realized that linking service transactions to trade could help them solve some of the problems they were confronting. Pan American Airlines faced difficulties to convince some countries that they ware as able as the national carriers to carry the international mail and they were convinced that these barriers were comparable to those barring trade in goods (Feketuky, 1998). But Pan Am would not become the central ideational entrepreneur, this role was taken up by the financial services7 companies who would take the lead in promoting services trade 6 Neoclassical trade theory comes to the conclusion that free trade leads to a maximization of global welfare, assuming that states are utility maximizing actors (Krasner, 1976). 7 Popularizing the concept „financial services‟ was one of the first efforts of American Express. The term was barely used before 1978 (Freeman, 1997). 11 liberalization., it were Ron Shelp and Hank Greenberg from American International Group (AIG) who saw the full potential for the services industry to link trade liberalization to services (Feketuky, 1998). In 1978 AIG was joined by the American Express Company (Amex)8 and they decided to aim for a broad liberalization of services, not just financial services, as this would make it easier to find allies in the process (Freeman, 1998, p. 184). Senior people from AIG, Amex and later Citicorp would become and remain for a long time the core ideational entrepreneurs in the services liberalization process. By using the language of trade liberalization, transnational corporations (TNC‟s) became able to frame domestic regulation, that was harming their business interests, as protectionism (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 46). Ideational lobbying US services activists started a massive information campaign to inform the US government of the importance of seeing services transactions as trade an linking this to the need to liberalize this trade. As major corporations they didn‟t faced a lot of difficulty getting access to the government. In the US, the new approach to services transactions provided a solution for the trade in goods deficit that was growing since the beginning of the 1970s (see figure 4). The normative framework also fitted with their pre-existing normative beliefs, favoring trade liberalization but at the same time gave an answer to the perceived problem that the power of the United States was declining (Destler, 2005). Figure 4: US Balance of Payments (BOP) in Goods and Services (1960-2005) 400 200 0 -200 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 Goods BOP Services BOP -400 -600 -800 -1000 Source: US Census Bureau (millions of US dollars) US services companies started lobbying the US government. Their first success, was the 1974 Trade Act that would include a request to the US president to work towards the international liberalization of “goods When American Express appointed James Robinson as CEO, he changed the business goals of the company, before, Amex was “strong in the credit card, travelers check, and other travel-related businesses.” Robinson made Amex a real „financial services‟ firm. This had implications for its government strategy. Before this change Amex had little to do with government interference but as a financial services firm, it was subject to a lot of regulation and had to become more active politically (Yoffie et al., 1985). 8 12 and services9”. In addition the Trade Act created a new advisory committee for trade negotiations that would include representatives of the services industry (US Trade Act, 1974). The US government became engaged in a learning process. They asked Bruce Wilson, a young professional in the Office of the Special Trade Representative, to make a study. This paper argued for the extension of the international trade system to include services, as these were considered of growing importance to the international economy and also need to be treated just in the international trading system. As a consequence, the White House Interagency Task Force on Services and the Multilateral Trade Negotiations was established to find out what barriers US services companies were facing in international commerce. The Commerce Department also commissioned a study of services trade by Wolf and Company, a private consulting firm. (Feketekuty, 1988). The US government understood that foreign restrictions on American companies were harming their interests but they “lacked a convincing argument that these were trade barriers (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 47).” There was a very close relationship between the actions of the US government and American business. James D. Robinson, the chairman of American Express became the chairman of the newly established senior advisory committee to the US trade representative on services trade policy and the government turned to the US Chamber of Commerce to make a study of the barriers that American services companies were facing abroad (Feketekuty, 1988). In the OECD the US government would take the lead in teaching other governments about their interests (see below). But they did this on the instigation of the services industry, as Feketekuty stated to “get the „pushy‟ chair of AIG, Hank Greenberg, off the USTR‟s back” (Kelsey, 2008, p. 61). US business lobbyists, especially AIG‟s Hank Greenberg and American Express‟ Harry Freeman, kept reminding the government of the importance of the services issue. Greenberg was appointed to the Presidential Advisory Committee for Trade Negotiations. Intergovernmental learning While the US government became more and more convinced of the importance of liberalizing international services trade, they also realized that encompassing multilateral negotiations on this subject need longer and deeper preparation than would be possible if services were included in the ongoing Tokyo round. However, the US succeeded in including some first references to services in some nontariff agreements, the Government Procurement Code, the Standards Code and the Subsidies code. At the same time they received an informal agreement to further discuss services in the OECD trade committee from the developed countries (Feketekuty, 1988). But foreign governments didn‟t share the belief that services where something that could be traded, “without a shared causal belief that services were indeed tradable, it was impossible to discuss the question coherently, much less negotiate (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 47).” While the other states didn‟t want to negotiate services liberalization in the Tokyo round, the United Popularizing the linking of goods and services is also at least partially due to the efforts of Harry Freeman of Amex. He claims to have written about 1600 letters to journalists and academics who used the term „goods‟ without adding „and services‟ (Freeman in Sauvé et al., 2000). 9 13 States received an informal concession that the developed countries would further discuss services in the frame of the OECD (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 47).” The US government launched a campaign in the OECD to find a consensus in support of multilateral trade negotiations on services liberalization. This campaign was led by Geza Feketekuty who represented the US in the OECD Trade Committee and had served before as a finance and trade economist at Citicorp. Most states still saw services as something that was not tradable and should be restricted by domestic regulations. Feketekuty started a campaign with studies and conferences and a public information campaign to “develop a core of government officials, business leaders, and academicians knowledgeable about trade in services, involved in the work on trade in services, and committed to the effort to build a consensus in support of multilateral negotiations (Feketekuty, 1988).” A paper distributed by Feketekuty in 1978 strongly framed services in a “trade liberalization discourse” (Kelsey, 2008, p. 62). The OECD-process of intergovernmental learning was divided in different phases. First states had to be convinced that there existed “such a thing as trade in services.” Second, states debated on “what aspects of trade should be studied.” Third, there were discussion on whether analyses should be based on industry-by-industry or on an aggregate cross-sectoral basis. The US, Japan, Australia and Norway wanted a cross-sectoral analysis. While only the UK was vehemently against such an approach, most other governments were at least skeptical (Feketuky, 1989, p. 63). The fourth phase concerned relating services issues to “existing trade concepts.” And the final phase was about “the possibility of developing meaningful rules and principles for trade in services (Feketekuty, 1988).” The process in the OECD allowed the US to build a “critical mass of support” to include services negotiations in the GATT negotiations (Kelsey, 2008, p. 58). That real learning happened can be seen by the fact that even before much services were really liberalized globally, the European Community incorporated internal services liberalization, that would go even further, in its 1992 program (European Commission, 1985). The EU saw in the liberalization of services trade, in which it already had a surplus, an opportunity to deal with its problems of declining trade balance in goods (see figure 5). In addition the idea of trade liberalization was consistent with its existing beliefs on market liberalization, engrained in the EU‟s policy programs 14 Figure 5: EU(15) trade balance in goods and services 10 200000 150000 100000 50000 Goods Balance Services balance 0 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2009 -50000 -100000 -150000 Source: WTO statistics database (millions of US dollars in 2009 prices) The next step of adapting beliefs occurred in the GATT. The US government started pushing the GATT. In 1981 the OECD ministers stated that barriers to trade in services had to be considered as topics for discussion in multilateral negotiations. The OECD process led most of the developed countries to reevaluate their interests and throughout the process they discovered that they had an “economic interest in trade in services (Feketekuty, 1988).” In the 1982 meeting of GATT trade ministers the US trade representative tried to “lay the intellectual groundwork” for a discussion on services liberalization but the members of the European Community (EC) were still uncertain about their specific interests in the issue and the LDC countries were completely unfamiliar with the conceptual framework of services liberalization. Developing countries had been totally absent from the OECD process and were strongly opposed to include a discussion of services in the GATT. The US had hoped establish a GATT committee on trade in services but failed. A compromise was reached, the “interested countries could prepare national studies of trade in services and that the GATT could arrange for an exchange of views based on such studies. This would be done in an informal committee under the chairmanship of Felipe Jaramillo, the Colombian Ambassador to the GATT. In this group industrialized countries and some newly industrializing countries (NIC‟s) started sharing causal beliefs on services trade (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 55). While there was no agreement on how to proceed, services liberalization became established as a topic of discussion in the GATT, this implied that states would have to develop reasoned positions on what their interests in the issue were” (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, pp. 52-53). States had to adapt a position and Prior to 1990: former GDR is excluded. Beginning 93: figures are affected by the Intrastat system of recording trade between EU member States. Under-recorded intra-EU imports have been adjusted by using the value of intraEU exports to obtain total imports 10 15 therefore needed ideas to form this position on an issue they often didn‟t really think before (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 53). As there were not many alternative causal explanations for services transactions, the trade discourse gains ground. Japan, and later Britain, Canada, France and Switzerland started supporting the American cause, also the EC re-evaluated its initially cautious “in light of the results of numerous analyses undertaken by national ministries and the Commission's interservices group (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 57).” As they also needed to develop a position on the services, the LDC‟s turned to the UNCTAD. In 1983 the UNCTAD secretariat was asked to study the effects of services on development (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 58) This painted a much more negative picture than earlier western studies, “the report challenged the validity of transposing concepts of deregulation and liberalisation from trade in goods to services (Kelsey, 2008, p. 67).” Thus at first, while the existing beliefs of services as something that should fall under the sovereign rule of each country, were discredited by technological and market evolutions, the new ideas initially failed to plant themselves in the belief systems of the LDC governments. While the consensus grew on the need for „an‟ agreement on international services trade, many negotiators had no clear idea on „what‟ agreement they really wanted. The intergovernmental learning had made them interested in an agreement but they were still uncertain on what agreement they preferred. In 1984 the Jaramillo group became an established committee that had the task to examine whether services should be included in the next round of multilateral negotiations. The meetings of the Jaramillo group led to the persuasion of quite some developing countries but not of India and Brazil. Many LDC‟s changed their preferences when they got better information (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, pp. 66-67), also the further research of the UNCTAD staff contributed to changing LDC preferences. While much of the UNCTAD research contributed to improving the intellectual grounding of the LDC‟s concerns about TNC “power and domestic regulatory objectives,” it also stated that LDC‟s could also benefit from some forms of multilateral liberalization (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 79). Mobilizing other constituents US business organized an information campaign. Shelp from AIG and Freeman and Spero from American Express organized conferences and lobbied Congress. They mobilized other American actors like the “Council for International Business, the Council of Foreign Relations, the National Foreign Trade Council, the Committee for Economic Development, the Conference Board, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the American Enterprise Institute (Feketekuty, 1988).” Also Citicorp got involved in the lobbying process and its CEO John S. Reed, would later succeed James Robinson as the chairman of the advisory committee when he moved up to the chairmanship of the President‟s Advisory Committee on Trade, and would later be succeeded by Maurice Greenberg of AIG. American Express took the initiative to found the US Coalition of Service Industries (USCSI) in 1982. The USCSI‟s objective is to expand “the multilateral trading environment to include more countries and more services (CSI, 16 2010).” The CSI was chaired by Harry Freeman and included among others representatives of Citicorp, Meryll Lynch and AT&T (Kelsey, 2008, p. 78). AIG‟s Shelp pushed the US Chamber of Commerce to establish a services committee (Feketekuty, 1988).” In addition to American actors, the service entrepreneurs started mobilizing foreign business. International mobilization was also done by the TPRC and the International Chamber of Commerce created in 1981 a working group on services, that would be driven by the US. In Britain Lloyd‟s of London was one of the firms establishing Liberalisation of Trade in Services Committee (LOTIS) in 1982. This committee would strongly cooperate with the CSI. Other international groups emerged, the Services World Forum was established in Geneva in 1986. Through the mobilization campaign, more and more companies started seeing themselves as consumers of services and made them change their position towards government regulation in the services sector (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 46; Woll, 2008, p. 51). Ideational feedback The role of the ideational entrepreneurs, the American financial services companies, was essential for starting the process, planting the seeds of an idea in the minds of US governmental actors. Once the US government was convinced, they took over the lead to educate other states of the benefits of services liberalization. During this learning process, the financial services companies remained important in assisting the government in its „teaching‟ and mobilized other US and international firms to support liberalization. Once the intergovernmental negotiations started, the role of the entrepreneurs became of lesser importance, focusing on keeping the pressure on the governments but contributing little more to the debate. While the role of the US business coalition was very important in launching the new idea and remained important as they worked in close collaboration with the US government in further promoting liberalization, they lost more and more control of the framing of the idea when the process became intergovernmental, first in the OECD, and even more when the process moved to the GATT. The idea became modified as new actors adapted the idea to fit more with their own interests. In its first version, services were considered to be almost equivalent to goods concerning how the GATT rules could be applied to them. The GATT principles, transparency, most favored nation (MFN) and national treatment would just have to be applied to services. But when the number of actors grew and more and more information became available, it became clear that it would not be so easy to fit services in existing GATT-rules. An important point of discussion that arose between the Americans and the European, was that the EU wanted to look at liberalization one sector at a time and develop rules for each sector, while the US preferred a generic agreement, covering all services sectors. This discussion evolved into a discussion about a positive-list versus a negative list approach. A negative list approach would develop rules that would be applied to all sectors, except those on the list. A positive list approach meant that only those sectors on the list would be covered by the agreement. Only the UK wanted to go along with the 17 United States approach of “across-the-board deregulation that simply eliminated long-standing social and other policy objectives (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 82).” European actors preferred a more “managed approach to liberalization” in opposition to the Americans who wanted to eliminate trade barriers quickly (Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 69), their classical liberal vision was replaced by the European idea of managed markets. Also the LDC‟s started modifying the idea to fit better with their own interests. They used the idea of services liberalization to promote the liberalization of (skilled and unskilled) labor migration by stating that migration was just the preferred mode of delivery for their „service providers,‟ and that this was the sector where they had a comparative advantage(Drake & Nicolaidis, 1992, p. 73). When the idea moved into the GATT negotiations, further changes were needed to adapt it to the existing structures of the GATT. In this way the idea evolved to fit with new actors existing preferences and beliefs. Effects on cooperation It was only when states starting sharing the basic concept of services as something that could be traded, that a discussion between states on cooperating on this issue became possible. If services were not seen as trade, there would be no need for cooperation between states. While at the end of the Uruguay round states still differed over whether it was in their interest to liberalize trade in services, nobody was still arguing that services were not something that could be traded. The claim that services transactions were, maybe not equivalent, but at least comparable to transactions of goods, became a fait accompli, creating the foundation for further discussions on how should be dealt with these discussions, but by linking trade in services and goods also a moral bias was created. The negative connotation of „protectionism‟ could now also be applied to domestic regulations covering services, while before making this link, it was much more difficult to attack and try to change other states domestic regulations as this was a question of sovereignty. Having everybody accept this notion of services as tradable things and linking it to a liberalization norm, made it easier for states to cooperate. As a consensus grew on the benefits of liberalization, it became easier to cooperate. By not only convincing state actors but also mobilizing a coalition of like-minded companies, that didn‟t know that they had something in common before, made concluding an agreement on services trade easier. Thus the lobbying activities of the US services companies made cooperation between states on services possible. The establishment of services transactions as international trade limited the range of options for future cooperation in the services sector. By establishing the core concepts of the idea, reframing services transaction as trade and fitting it into an organization working towards trade liberalization, the WTO, they limited the debate to a trade discourse where it would be those who oppose liberalization who would have to justify why they want exceptions, instead of those promoting liberalization as it was before when the major idea governing services was national sovereignty. 18 3. Conclusion While this study of the process leading to services liberalization is only a very tentative first test, this case confirms my hypotheses. I demonstrated at the different steps in the process why the idea of services liberalization was first adopted by US services firms, then by the American government, later the European negotiators and finally also some LDC‟s. In each of these steps the idea could only be adopted because the availability of more and more information on market and technological evolutions made the existing beliefs less and less suitable to explain and guide services transactions. This created a need for new beliefs. Those new beliefs were found in a set of ideas that were (or became) congruent with the actors‟ other beliefs and provided an interesting solution to fill the void. These ideas easily reached decision makers as they were promoted by powerful business actors who had access to different parts of the governments and had an international network. Through a process of indirect influence these ideas travelled further between the American and western governments and later to the LDC‟s and foreign business actors. But at the same time this process led to a modification of the ideas as they were originally proposed by the ideational entrepreneurs. These modified ideas created a partially shared understanding of the issue of international services transactions, framing it as a trade issue. This made it possible for states to cooperate on this issue and at the same time limited the number of potential agreements. 19 Bibliography Acharya, A. (2004). How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism. International Organization, 58(2), 239-275. Adler, E. (1992). The Emergence of Cooperation - National Epistemic Communities and the International Evolution of the Idea of Nuclear Arms-Control. International Organization, 46(1), 101-145. Adler, E., & Haas, P. M. (1992). Epistemic Communities, World-Order, and the Creation of a Reflective Research-Program - Conclusion. International Organization, 46(1), 367-390. Béland, D. (2009). Ideas, institutions, and policy change. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(5), 701718. Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 611-639. Blyth, M. (2001). The transformation of the Swedish model - Economic ideas, distributional conflict, and institutional change. World Politics, 54(1), 1-+. Boudon, R. (2003). Beyond rational choice theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 1-21. Bouwen, P. (2004). Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research, 43(3), 337-369. Campbell, J. L. (1998). Institutional analysis and the role of ideas in political economy. Theory and Society, 27(3), 377-409. CSI. (2010). About CSI. Retrieved 17/05/2010, from http://www.uscsi.org/about/ Culpepper, P. D. (2008). The politics of common knowledge: Ideas and institutional change in wage bargaining. International Organization, 62(1), 1-33. Daugbjerg, C. (2008). Ideas in two-level games - The EC-United States dispute over agriculture in the GATT Uruguay Round. Comparative Political Studies, 41(9), 1266-1289. Destler, I. M. (2005). American trade politics (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics. Drake, W. J., & Nicolaidis, K. (1992). Ideas, Interests, and Institutionalization - Trade in Services and the Uruguay Round. International Organization, 46(1), 37-100. Elster, J. (1995). Strategic Uses of Argument. In K. J. Arrow, R. H. Mnookin, L. Ross, A. Tversky & R. B. Wilson (Eds.), Barriers to conflict resolution (1st ed., pp. 237-257). New York: W.W. Norton. European Commission. (1985). Completing the Internal Market. White Paper from the Commission to the European Council. (Milan, 28-29 June 1985). Retrieved. from. Evans, P. B., Jacobson, H. K., & Putnam, R. D. (1993). Double-edged diplomacy : international bargaining and domestic politics. Berkeley: University of California Press. Feketekuty, G. (1988). International trade in services : an overview and blueprint for negotiations. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Pub. Co. Feketuky, G. (1989). Dealing with Trade in Services in the Uruguay Round. In A. Bressand & K. Nicolaïdis (Eds.), Strategic trends in services : an inquiry into the global service economy (pp. 189-206). New York: Harper & Row, Ballinger Division. Feketuky, G. (1998). Trade in Services - Bringing Services into the Multilateral Trading System. In J. N. Bhagwati & M. Hirsch (Eds.), The Uruguay Round and beyond : essays in honor of Arthur Dunkel (pp. 79-100). [Ann Arbor, Mich]: University of Michigan Press. Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International norm dynamics and political change. International Organization, 52(4), 887-+. Freeman, H. L. (1997). A Pioneer's View of Financial Services Negotiations in the GATT and in the World Trade Organization: 17 Years of Work for Something or Nothing? The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance - Issues and Practice, 22(July), 392-399. Freeman, H. L. (1998). The Role of Constituents in U.S. Policy Development. In A. V. Deardorff & R. M. Stern (Eds.), Constituent interests and U.S. trade policies (pp. 183-182). Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press. 20 George, A. L. (1980). Presidential decisionmaking in foreign policy : the effective use of information and advice. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. Gourevitch, P. A. (1989). Keynesian politics: the political sources of economic policy choices. In P. A. Hall (Ed.), The Political power of economic ideas : Keynesianism across nations (pp. 87-106). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Griffiths, B. (1975). Invisible barriers to invisible trade. London: Macmillan for the Trade Policy Research Centre. Habermas, J. (1984). The theory of communicative action. Boston: Beacon Press. Hall, P. A. (1993). Policy Paradigms, Social-Learning, and the State - the Case of Economic PolicyMaking in Britain. Comparative Politics, 25(3), 275-296. Hansen, R., & King, D. (2001). Eugenic Ideas, Political Interests, and Policy Variance: Immigration and Sterilization Policy in Britain and the U.S. World Politics, 53(2), 237-263. Hirschman, A. O. (1989). How the Keynsian Revolution Was Exported from the United States, and Other Comments. In P. A. Hall (Ed.), The Political power of economic ideas : Keynesianism across nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Ikenberry, G. J. (1992). A World-Economy Restored - Expert Consensus and the Anglo-American Postwar Settlement. International Organization, 46(1), 289-321. Keck, M. E., & Sikkink, K. (1998). Activists beyond borders : advocacy networks in international politics. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. Kelsey, J. (2008). Serving whose interests? : the political economy of international trade in services agreements. New York: Routledge-Cavendish. Klandermans, B. (1984). Mobilization and Participation - Social-Psychological Expansions of Resource Mobilization Theory. American Sociological Review, 49(5), 583-600. Krasner, S. D. (1976). State Power and Structure of International-Trade. World Politics, 28(3), 317347. Levy, J. S. (2003). Political Psychology and Foreign Policy. In D. O. Sears, L. Huddy & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology (pp. 253-284). New York: Oxford University Press. Martin, C. J. (1991). Shifting the burden : the struggle over growth and corporate taxation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Martin, C. J. (1995). Nature or Nurture - Sources of Firm Preference for National-Health Reform. American Political Science Review, 89(4), 898-913. McNamara, K. R. (1998). The currency of ideas : monetary politics in the European Union. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. McNamara, K. R. (1999). Consensus and constraint: Ideas and capital mobility in European monetary integration. Journal of Common Market Studies, 37(3), 455-476. Meunier, S. (2005). Trading voices : the European Union in international commercial negotiations. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Milner, H. V., & Rosendorff, B. P. (1997). Democratic politics and international trade negotiations Elections and divided government as constraints on trade liberalization. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41(1), 117-146. Moravcsik, A. (1997). Taking preferences seriously: A liberal theory of international politics. International Organization, 51(4), 513-&. Moravcsik, A. (1998). The choice for Europe : social purpose and state power from Messina to Maastricht. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. Muller, H. (2004). Arguing, bargaining and all that: Communicative action, rationalist theory and the logic of appropriateness in international relations. European Journal of International Relations, 10(3), 395-435. Naurin, D. (2010). Most Common When Least Important: Deliberation in the European Union Council of Ministers. British Journal of Political Science, 40, 31-50. Pappi, F. U., & Henning, C. H. C. A. (1999). The organization of influence on the EC's common agricultural policy: A network approach. European Journal of Political Research, 36(2), 257281. 21 Parsons, C. (2003). A certain idea of Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Putnam, R. D. (1988). Diplomacy and Domestic Politics - the Logic of 2-Level Games. International Organization, 42(3), 427-460. Risse-Kappen, T. (1994). Ideas Do Not Float Freely - Transnational Coalitions, Domestic Structures, and the End of the Cold-War. International Organization, 48(2), 185-214. Risse-Kappen, T., Ropp, S. C., & Sikkink, K. (1999). The power of human rights : international norms and domestic change. New York: Cambridge University Press. Risse, M. (2000a). What is rational about Nash equilibria? Synthese, 124(3), 361-384. Risse, T. (2000b). "Let's argue!'': communicative action in world politics. International Organization, 54(1), 1-+. Risse, T., Ropp, S. C., & Sikkink, K. (1999). The power of human rights : international norms and domestic change. New York: Cambridge University Press. Sauvé, P., & Gillespie, J. (2000). Financial Services and the GATS 2000 Round. Brookings-Wharton Papers on Financial Services: 2000, 423-465. Schelling, T. C. (1960). The strategy of conflict. Cambridge,: Harvard University Press. Schimmelfennig, F. (2001). The Community Trap: Liberal Norms, Rhetorical Action, and the Eastern Enlargement of the European Union. International Organization, 55(1), 47-80. Schumpeter, J. A. (1943). Capitalism, socialism, and democracy (6th ed.). London: Routledge. Simmons, B. A., & Elkins, Z. (2004). The Globalization of Liberalization: Policy Diffusion in the International Political Economy. The American Political Science Review, 98(1), 171-189. Tarar, A. (2001). International bargaining with two-sided domestic constraints. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 45(3), 320-340. Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Learning in U.S. and Soviet foreign policy: In search of an elusive concept. In G. W. Breslauer & P. E. Tetlock (Eds.), Learning in U.S. and Soviet foreign policy (pp. 20-61). Boulder: Westview Press. Truman, D. B. (1951). The governmental process; political interests and public opinion ([1st ed.). New York,: Knopf. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgement under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124-1131. Trade Act of 1974, (1974). Van den Hoven, A. (2002). Interest group influence on trade policy in a multilevel polity: Analysing the EU position at the Doha WTO Ministerial Conference EUI Working Paper, RSC No. 2002/67., 1-39. Woll, C. (2008). Firm interests : how governments shape business lobbying on global trade. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Woll, C. (2009). Trade Policy Lobbying in the European Union: Who Captures Whom? In D. Coen & J. J. Richardson (Eds.), Lobbying the European Union : institutions, actors, and issues (pp. 277297). Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. Woods, N. (1995). Economic Ideas and International-Relations - Beyond Rational Neglect. International Studies Quarterly, 39(2), 161-180. Yoffie, D. B., & Bergenstein, S. (1985). Creating Political Advantage - the Rise of the Corporate Political Entrepreneur. California Management Review, 28(1), 124-139. 22