Investing With Your Values

IN THIS REPORT

Interest in Socially Aware Investing Is Growing Rapidly

What Is Socially

Aware Investing? . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

More and more investors around the world want their portfolios to

reflect their values. In the United States alone, socially aware investing

has increased more than 324% since 1995—significantly faster than

the overall market. In 2007, SAI assets totaled $2.71 trillion—about

11% of all assets under management. Over the past two years, the pace

of growth in socially aware investing has continued to outstrip that of

conventional investment management by a wide margin.1

Why Socially Aware Investing?

If your values are as important to you as your financial future, consider

these compelling reasons to participate in socially aware investing:

It allows you to invest in a manner that is true to your values and the issues that are important to you.

It is an established discipline with a long-term track record of results.

There are many attractive investment options that are likely to reflect your principles, so you do not have to check your values at the door when seeking to meet your investment objectives.

n

n

n

Do Social and Environmental

Issues Affect Returns? . . . . . . . . . 3

How Does Socially

Aware Investing Work? . . . . . . . 5

Risks Particular to

Screened Portfolios . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Socially Aware

Investment Choices . . . . . . . . . 10

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

WHAT IS SOCIALLY AWARE INVESTING?

DO SOCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUES AFFEC T RETURNS?

Socially aware investing (SAI) enables

individuals and institutions to put their money

to work in a manner that is consistent with their

values and societal concerns. As with any other

investment approach, socially aware investors

choose investments based on their return and

risk potential. In addition to considering risk

and return, however, socially aware investors

take social or ethical criteria into account

when deciding whether to buy, sell, or hold

certain securities. These investors take into

consideration company policies and practices

around issues that are important to them—for

example, environmental protection or product

safety. In this manner, investors are able to invest

in companies whose philosophies and activities

are compatible with their own principles.

You may assume that socially aware investing

hurts portfolio performance. However, research

shows that socially aware portfolios have the

potential to offer competitive returns relative to

their non-SAI peers, as long as they are properly

diversified and managed with an awareness of the

impacts of the social investment criteria (screens).

Last year, researchers at Lehigh University

compared the returns of four groups of

portfolios, which use KLD Research & Analytics

social screens, to the returns of the Russell

3000 U.S. stock index. The authors concluded

that there were no significant differences in

the returns of the screened portfolios over the

1991 to 2004 time period under study. “There

is no cost to being good by investing according

to [SAI] screens. In other words, investors are

no worse off investing in accordance with their

social beliefs.”3

Most studies covering long time periods show

that social investors have done as well, on

average, as conventional investors. For instance,

a study that examined the performance of 103

U.K., German, and U.S. SAI-screened mutual

funds from 1990 to 2001 found no difference

in risk-adjusted returns between mutual funds

that screen their holdings based on SAI criteria

and unscreened mutual funds. The authors also

found that screened portfolios that have been in

existence longer appear to perform better than

younger ones.2 This conclusion underscores the

importance of working with portfolio managers

who have experience running socially aware

investment portfolios.

Another study that looked at the returns of

SAI-screened bond mutual funds for the period

of 1987 to 2003 found that their returns were

competitive with or even slightly higher than

those of their unscreened counterparts.4

1. Social Investment Forum, 2007 Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the United States, 2008.

2. Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Rob Bauer, Kees Koedijk, and Roger Otten, “International Evidence on Ethical Mutual Fund Performance and Investment Style,” January 2002.

3. Anne-Marie Anderson and David H. Myers, Lehigh University, “Performance and Predictability of Social Screens,” June 26, 2007.

4. Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Jeroen Derwall and Kees Koedijk, “Socially Responsible Fixed-Income Funds,” working paper, Erasmus University, January 2006.

2

3

HOW DOES SOCIALLY AWARE INVESTING WORK?

who screen stocks based on human-resource

criteria may be compensated with higher

returns. Indeed, a recent study that covered the

1998 to 2005 time period supports that idea.

The study found that, even after adjusting

for factors such as the size of the company,

stocks that were on Fortune magazine’s list

of the “100 Best Companies to Work For” in

America had better returns than the overall

stock market.8

Moreover, SAI strategies that focus on certain

areas or issues have an increased potential to

outperform. These areas include:

■■

Governance. Corporate governance—how

senior managers and boards of directors run

their companies—is critically important to

all investors. One recent study found that

companies that received high governance

scores outperformed those with low scores

over three-, five-, and ten-year periods.5

Another study showed that firms with superior

corporate governance policies notably

outperformed those with weak governance in

the decade of the 1990s.6

■■

Also worthy of note is the case of the

California Public Employees Retirement

System (CalPERS). CalPERS places some of

the companies in which it invests—those most

in need of improved corporate governance—

on a focus list. CalPERS engages these firms

in dialogue with the goal of improving their

governance practices, especially in the areas of

discipline, independence, accountability, and

transparency. A study that covered the 1992

to 2005 time period found that, on average,

when CalPERS announced the addition of a

company to the focus list, the stock of that

company rose 0.23% in the day following the

announcement. This seemingly small stock

price rise increased shareholder wealth by

almost $3.1 billion over those 14 years.7

■■

Environment. Several studies support

the notion that companies that manage

environmental risks most effectively tend to

generate higher returns than their industry

peers. For example, an Erasmus University

study, which covered the 1995 to 2003 time

period, concluded that stocks of companies

with high environmental ratings markedly

outperformed poorly rated ones during

the period under study.9 Perhaps good

environmental management is an indicator

of good corporate management and can help

reduce the risk of profit disappointments due

to environmental problems.

These examples suggest that the stock market

has not fully appreciated the financial benefits

earned by companies with superior employee

relations, governance, and environmental

policies. It is possible that such companies

could potentially enjoy higher returns than their

peers over time. However, it is important to

remember that other issues of concern to social

investors may have a neutral or even negative

effect on performance. For that reason, we agree

with the mainstream of performance studies,

which indicate that socially aware investing has

generated competitive returns.

Employee Relations. Employees matter to

business performance. Yet the human resource

policies and practices of many companies are

not widely followed by the general investment

community. So it is no surprise that investors

Some investors, notably institutions in Europe,

find the use of negative screening too restrictive

from a financial standpoint. These investors

have begun to adopt a “best-in-class” social

investment approach. As an example, many

companies in the oil and gas industry face

environmental challenges—so much so that

some environmental investors exclude them

all. This would have been a potentially costly

decision in recent years, as many energy stocks

have been excellent performers relative to the

overall stock market. Instead of excluding

all traditional energy companies, a best-inclass investor would try to identify superior

environmental performers within the group and

invest in those.

Everybody’s values are different. Therefore, you

can typically decide the ways and degrees to

which you want to implement socially aware

investing in your portfolio.

Two Approaches to Socially Aware Investing:

Negative Versus Positive Screens

Socially aware investing has been traditionally

associated with negative screening. Negative

screening excludes companies or industries

whose business policies and/or practices do not

meet the investors’ SAI criteria. For example,

if you are concerned about the environment,

you may choose to screen out companies whose

practices you consider to be harmful to the

environment. While this approach can exclude

from a portfolio any company or industry that

does not meet strict criteria on all levels, for

some socially aware investors, it can prove too

restrictive.

There are many tools to help ensure that your

portfolio reflects your values. Which tools you

use will depend on how much emphasis you

wish to place on positive versus negative factors

and how stringent you wish your screening

approach to be.

As an answer to those investors who would

prefer to be proactive rather than reactive, in

recent years, the SAI field has shifted toward

positive screening. Instead of just eliminating

objectionable companies, a social investor using

positive screening might seek to proactively

include companies that show positive traits in

the areas of concern. For instance, if you are

concerned about the environment, you may use

positive screens to select alternative energy or

environmental remediation companies in your

portfolio. More broadly, positive screening may

identify lists of superior performers in various

social areas, such as the “100 Best Companies

to Work For” in America, or companies with

superior corporate governance.

The solutions are as diverse as social investors

themselves. Some apply just one or two simple

exclusionary SAI screens, while others seek out

more complex social investment programs that

involve multitiered analysis of diverse issues. In

either case, whenever possible, companies that

do not meet the investor’s standards should

be replaced with comparable, fundamentally

attractive companies that do adhere to

the investor’s financial and values-based

investment criteria.

5.Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Lawrence D. Brown and Marcus L. Caylor, “The Correlation Between Corporate Governance and Company Performance,” Institutional Shareholder Services, 2004.

6. Paul Gompers, Joy L. Ishii, and Andrew Metrick, “Corporate Governance and Equity Prices,” working paper #8449, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2001.

7. Brad M. Barber, U.C. Davis, “Monitoring the Monitor: Evaluating CalPERS’ Activism,” November 2006.

8. Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Alex Edmans, “Does the Stock Market Fully Value Intangibles? Employee Satisfaction and Equity Prices,” working paper, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007.

9. Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility, Jeroen, Derwall, Nadja Gunster, Rob Bauer, and Kees Koedijk, “The Eco-Efficiency Premium Puzzle,” .Financial Analysts Journal, March 2005.

4

5

Social Awareness Investment Trends

■■

The first socially aware investors were, for the

most part, motivated by religious concerns.

As a result, their emphasis was primarily

on excluding a relatively small group of

alcohol, tobacco, and gambling companies

(the so-called “sin stocks”). Over the past

several years, however, the numbers of styles,

coverage, and asset classes within SAI have

expanded dramatically.

Different geographical areas tend to trend

culturally toward one particular approach

over another. For example, in Europe, the

“sustainability” model, using best-in-class

techniques, has taken precedence and accounts

for a large and growing slice of assets under

management. In Asia, trends vary widely across

the region. The largest concentration of assets

in more developed markets, such as Australia,

focus on ethical portfolios, green loans, and

community finance but address environmental

concerns to a lesser degree than in the United

States and Europe. In developing Asian countries

such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore, the

preponderance of investment interest is in faithbased funds.

■■

■■

In the United States, the consensus leaders in

the mutual fund market have all moved their

screening process toward a more progressive/

sustainable approach. This reflects a more

mainstream interest in social investing, driven

both by changes in the makeup of society and

news events in recent years. We have seen a

particular increase in interest in three areas:

Corporate Governance. The corporate

governance failures of the early 2000s were

front-page news and resulted in significantly

heightened awareness of these issues, as well

as specific legislation (for example, SarbanesOxley) to address these concerns. Following

the scandals at Enron, WorldCom, and

elsewhere, ethicists such as Lynne Sharp Paine

at the Harvard Business School have argued

that society’s expectations for corporate

behavior have permanently risen.10 And, as we

have seen, there is some evidence that suggests

that paying attention to corporate governance

could be beneficial for investment returns.

Alternative Energy. The surge in the price of

energy this decade has created an enormous

subsidy for alternative energy, and the field is

attracting significant new investment flows.

Famous energy entrepreneur T. Boone Pickens

recently announced an initiative intended to

popularize wind power in the south-central

United States.

Stakeholder Issues. There is a growing

consensus that good corporate management

includes taking into consideration a variety

of stakeholders, in addition to shareholders.

A myopic focus on shareholders may be

financially beneficial over the short term.

However, many corporate management

teams have learned that short-term gains may

come at the cost of problems in the future.

For instance, several large U.S. retailers

have found it difficult to open new stores in

desirable communities because of reputational

problems. The shareholders in these firms have

a right to ask whether the financial benefits

accrued were worth the negative impact on

future growth.

Other social investment strategies include:

■■

■■

Community Investing. This strategy

involves investments in community

development financial institutions, which

offer disadvantaged communities access to

banking services and capital that they might

otherwise not have. These services can enable

people with low incomes to improve their

lives and enhance their communities through

new businesses, job creation, and community

betterment projects.

.Shareholder Advocacy. Certain money

managers, mutual funds, and institutional

investors—such as religious groups,

foundations, and public government funds—

also address their social concerns through

shareholder advocacy. These advocates

engage companies in dialogues to persuade

them to make improvements in specific areas

of concern.

Some of these investors also use their power as

shareholders to propose shareholder resolutions

on certain issues, actively vote their proxies

in favor of such resolutions, and take other

related actions. From 2005 through mid-2007,

185 U.S.-based money managers, institutional

investors, and mutual funds—with $723 billion

in total assets—filed resolutions on social,

corporate governance, or environmental issues.11

10. Lynn Sharp Paine, Value Shift: Why Companies Must Merge Social and Financial Imperatives to Achieve Superior Performance, 2004.

11. Social Investment Forum, 2007 Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the United States, 2008.

6

7

RISKS PARTICULAR TO SCREENED PORTFOLIOS

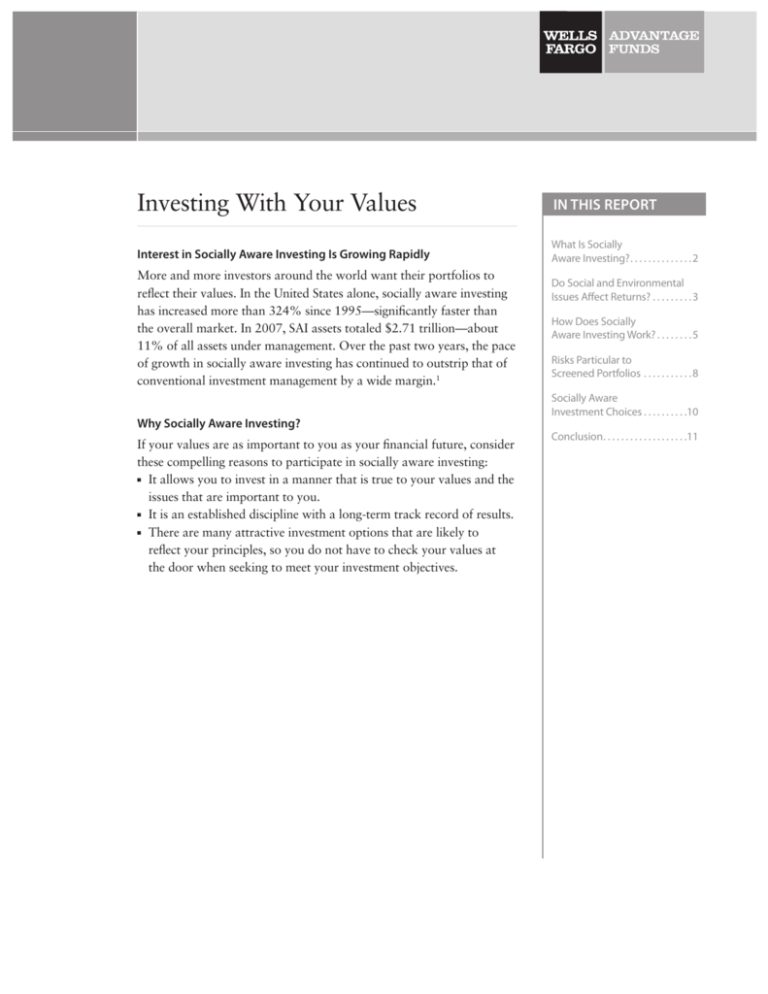

Now consider SAI indices that apply

environmental screens. Between January 2004

and May 2008, a typical SAI index might have

allocated approximately 4% less to the energy

sector than a comparable non-SAI index.

However, during that time period, energy

stocks generally performed better than the

overall stock market. As Figure 1 illustrates,

during that period of time, the Russell 1000

Integrated Oil Index beat the total Russell 1000

Index by approximately 130%. As a result,

underweighting the energy sector negatively

affected the SAI index performance relative

to that of the conventional index. However,

carefully managing sector allocations could

have mitigated or potentially reduced this

source of underperformance. Managers of

actively managed, socially screened portfolios

can address this type of risk by bringing the

weighting of the energy sector in line with the

broader market index.

To be successful, chess players must understand

the risks they encounter and evaluate the most

likely outcome of alternative moves. The same

strategy applies to managing SAI portfolios,

as they represent different sets of economic

opportunities from those of more broadly

based market indices. To achieve competitive

returns, it is critical that your portfolio manager

understands and properly manages the risks

of your SAI portfolio. For instance, excluding

securities or sectors from a portfolio can change

its risk profile by altering certain characteristics—

such as market capitalization, growth/value tilt,

and exposure to economic sectors—which could

affect the portfolio’s performance relative to

conventional benchmark indices.

Consider a portfolio that avoids investing

in companies that are involved in alcohol,

gambling, and tobacco. It will typically have a

smaller allocation to the industrials and basic

materials sectors than conventional portfolios

and thus have a larger allocation to financial,

consumer cyclical, technology, and health care

industries. As a result, the portfolio could have

a greater tilt toward growth-style securities

than its nonscreened counterparts. Unless the

portfolio manager adjusts the sector allocation

to be more style neutral, this screened portfolio

could likely perform better than comparable

nonscreened portfolios when growth sectors

are doing well but underperform when growth

sectors are out of favor.

8

Figure 1

Figure 2

Energy Stocks Have Recently Outperformed the Overall Stock Market

Total Russell 1000 Index vs. Russell 1000 Integrated Oil Index

January 2004 to June 2008

The Automobile Sector Has Recently Underperformed the Overall Stock Market

Total S&P 500 Index vs. Its Automobile Manufacturing Segments

December 31, 2001, to June 30, 2008

150%

50%

Russell 1000 Index

130%

40%

Russell 1000 Integrated Oil Index

S&P 500 Automobile and Components Index

S&P 500 Index

30%

110%

20%

90%

10%

70%

0%

50%

-10%

30%

-20%

10%

-30%

-10%

-30%

Dec 03

-40%

-50%

Jun 04

Dec 04

Jun 05

Dec 05

Jun 06

Dec 06

Jun 07

Dec 07

Dec 01 Jun 02 Dec 02 Jun 03 Dec 03 Jun 04 Dec 04 Jun 05 Dec 05 Jun 06 Dec 06 Jun 07 Dec 07 Jun 08

Jun 08

Source: Bloomberg, 6-8-08

Source: Bloomberg, 6-8-08

Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

Although some of the sectors that are typically

excluded from screened portfolios can

outperform or underperform the broad stock

market, you as a social investor could potentially

profit from excluding certain industries. For

instance, as Figure 2 shows, between December

31, 2001, and June 30, 2008, the automobile

sector of the S&P 500 Index—which is often

underweighted in SAI portfolios—had a lower

return than the total S&P 500 Index. So by

having a smaller allocation to the automobile

segment than did the total S&P 500 Index,

screened portfolios possibly could have enjoyed

higher returns than the total S&P 500 Index

during that period.

We strongly believe that SAI investors and their

portfolio managers must carefully monitor and

control these kinds of risks to avoid unintended

bets and achieve consistent and competitive

returns. To that end, your portfolio manager

should carefully identify the securities to be

excluded from your SAI portfolio and offset the

gap created by the exclusion of those securities.

Ultimately, socially aware investing is not

without risks or challenges. However, if done

properly, socially aware investing can deliver

competitive returns and allow you to own

attractive securities that are consistent with

your values.

9

SOCIALLY AWARE INVESTMENT CHOICES

Socially aware investing is flourishing as more

and more investors want their investments to

be consistent with their principles and societal

concerns. Today, you have more options

than ever before to help you maintain a welldiversified portfolio that truly reflects your

personal values.

■■

Figure 3

If you wish to participate in shareholder

advocacy, there are some money managers and

mutual funds that engage in this SAI strategy.

Please consult with your investment professional

to determine which socially aware investment

options are appropriate for you. We urge you

to consider your socially aware investments in

the context of your entire portfolio. Work with

your investment professional to ensure that

your portfolio, as a whole, is suitable for your

financial circumstances and goals, adequately

diversified, likely to meet your return objectives,

and consistent with your level of risk tolerance

and other investment constraints.

Mutual Funds. In the United States alone, there

were about 154 socially aware mutual funds

in 2007. These mutual funds cater to investors

with a wide range of political backgrounds

and social concerns. As Figure 3 shows, there

are socially screened products for just about

any set of values.12

Socially aware investing is a respected discipline

in which interest is growing rapidly around

the world. Investors are increasingly concerned

about social, environmental, and ethical

issues that affect our world, and corporations

are responding. As a result, today, nearly

one of every nine dollars under professional

management in the United States is invested

using social and environmental criteria.13

There Are Socially Screened Products for Just About Any Set of Values

Social Screening by All Funds, 2007

$174.1

Tobacco

Alcohol

$158.1

Labor

If an SMA is not appropriate for you, there are

plenty of other options. These include:

■■

Closed-End Funds. These are investment

companies that issue a fixed number of shares.

The shares are listed on a stock exchange and

traded in the secondary market. The assets

in these funds can be invested by the fund

manager in stocks, bonds, and other securities.

If you are interested in community investing,

you can place capital directly in community

development banks, community development

credit unions, and community development loan

funds. Alternatively, you can invest in investment

products that spread investors’ capital across

these institutions.

Customized options are available to wealthier

investors through socially screened separately

managed accounts (SMAs). This type of account

can be tailored to your investment needs and

personal values. If you have an SMA, you can

work with your portfolio manager to develop

and apply specific social and environmental

criteria so that your portfolio is consistent

with your societal, religious, and ethical goals.

Separately managed accounts typically require a

high minimum initial investment, however, and

you are likely to need a large amount of money

to invest in order to maintain an adequately

diversified portfolio.

■■

Conclusion

$48.1

$44.5

Environment

Defense/Weapons

$42.2

Community Relations

$41.8

Gambling

$41.2

Products/Services

$38.6

EEO/Equality

$34.0

Human Rights

Corporate Governance

$30.0

$21.1

Pornography

$18.3

Faith-Based

$17.7

Abortion

$14.5

Animal Testing

$14.1

Sudan

Other*

$0

The swift growth in socially aware investing

is also a result of the fact that portfolio

managers have proven that SAI portfolios offer

potential for competitive returns that is similar

to conventional investing. Studies that have

analyzed the performance of SAI portfolios over

long periods of time have shown that socially

aware investors have done as well, on average,

as conventional investors.

We believe that the best way to participate

in socially aware investing is to select an

experienced portfolio manager or fund that

has a recognized track record in successfully

navigating the risks specific to this investment

style. There are many competitive SAI

investment options to match your unique values

and social concerns. We are confident that if you

choose socially aware investing, you will have

the satisfaction of knowing that your money is

being put to work in a manner that reflects your

core values and helps you achieve your longterm financial goals.

$12.1

$10.0

$25

$50

$75

$100

$125

$150

$175

$200

Total Net Assets ($ Billions)

Source: Bloomberg, 6-8-08

Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

Source: Social Investment Forum, 2007 Report on Socially Responsible

Investing Trends in the United States, July 2008.

*Among the “other” screens used are issues such as “anti-family”

entertainment and “alternative lifestyles,” health care, public health,

biotechnology, medical ethics, cultural concerns, corporate charitable and

political contributions, youth concerns, and terrorist states.

Exchange-Traded Funds. There are several

socially screened exchange-traded funds

(ETFs). These ETFs replicate the securities

held by a particular socially aware investment

index and can be traded on a stock exchange

as if they were stocks.

12. As measured by total net assets under management. Source: Social Investment Forum, 2007 Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the

United States, 2008.

10

13. Social Investment Forum, 2007 Report on Socially Responsible Investing Trends in the United States, 2008.

11

Stock fund values fluctuate in response to the activities of individual

companies and general market and economic conditions. Bond fund

values fluctuate in response to the financial condition of individual issuers,

general market and economic conditions, and changes in interest rates. In

general, when interest rates rise, bond fund values fall and investors may

lose principal value. Some funds, including nondiversified funds and funds

investing in foreign investments, high-yield bonds, small and mid cap stocks,

and/or more volatile segments of the economy, entail additional risk and

may not be appropriate for all investors. Consult a Fund’s prospectus for

additional information on these and other risks.

Carefully consider a fund’s investment objectives, risks, charges, and

expenses before investing. For a current prospectus, containing this and

other information, call 1-888-877-9275 or visit www.wellsfargo.com/

advantagefunds. Read it carefully before investing.

Asset allocation and diversification do not assure or guarantee better performance and cannot

eliminate the risk of investment losses.

The Russell 3000® Index measures the performance of the 3,000 largest U.S. companies based on total

market capitalization, which represents approximately 98% of the investable U.S. equity market.

The Russell 1000® Index measures the performance of the 1,000 largest companies in the Russell 3000

Index, which represents approximately 92% of the total market capitalization of the Russell 3000 Index.

The Russell 1000® Integrated Oil Index is a subset of the Russell 1000 Index; it includes those integrated

oil companies included in the Russell 1000.

The S&P 500 Index consists of 500 stocks chosen for market size, liquidity, and industry group

representation. It is a market-value weighted index, with each stock’s weight in the index

proportionate to its market value.

The S&P 500 Industry Multi-Utilities Index is a capitalization-weighted index calculated on a total

return basis with dividends reinvested. It is a subset of the S&P 500; it includes those multi-utilities

companies included in the S&P 500 Index.

The S&P 500 Sub-Industry Automobile Manufacturers Index is a capitalization-weighted index

calculated on a total return basis with dividends reinvested. It is a subset of the S&P 500; it includes

those automobile manufacturers included in the S&P 500 Index.

More information about Wells Fargo Advantage Funds®

is available free upon request. To obtain literature,

please write, e-mail, or call:

Wells Fargo Advantage Funds

P.O. Box 8266

Boston, MA 02266-8266

E-mail: wfaf@wellsfargo.com

Investment Professionals: 1-888-877-9275

Web site: www.wellsfargo.com/advantagefunds

You cannot invest directly in an index.

Wells Fargo Funds Management, LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary

of Wells Fargo & Company, provides investment advisory and

administrative services for Wells Fargo Managed Account Services

and Wells Fargo Advantage Funds. Other affiliates of Wells Fargo &

Company provide subadvisory and other services for the Funds. The

Funds are distributed by Wells Fargo Funds Distributor, LLC, Member

FINRA/SIPC, an affiliate of Wells Fargo & Company. 112247 10-08

© 2008 Wells Fargo Funds Management, LLC. All rights reserved.

www.wellsfargo.com/advantagefunds

100%

Cert no. XX-XXX-XXXXXX

Printed with soy ink

FAWP0013 10-08