The American Journal of Surgery (2013) 206, 613-618

Editorial Opinion

Did James A. Garfield die of cholecystitis? Revisiting the

autopsy of the 20th president of the United States

Theodore N. Pappas, M.D.a, Shahrzad Joharifard, M.D.b,*

a

Department of Surgery, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA; bDepartment of Surgery, University of British Columbia,

Faculty of Medicine, 910 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V5Z 4E3

Historians have reviewed the shooting and ultimate

demise of James A. Garfield since 1881, the year of his

assassination. Remarkably, rather than faulting the assassin,

nearly every author has blamed the President’s death on the

physicians who cared for him in the 80 days after the

shooting. Most historians have argued that Garfield’s physicians mismanaged the bullet wound on his back, leading to

iatrogenic starvation, uncontrolled sepsis, and finally death.

This article reconstructs the events after the shooting and

revisits Garfield’s postinjury clinical course in light of the

anatomic facts revealed by his autopsy. Based on this

reconstruction, we argue that the President’s medical team

followed the standard of care of the era. Furthermore, our

detailed analysis of Garfield’s postmortem examination

leads us to contend that the President died not as a result of

his physicians’ alleged incompetence but rather from a late

rupture of a splenic artery pseudoaneurysm after suffering

from a complicated course of acute cholecystitis.

entering the station, Garfield was approached from behind

by a mentally unstable attorney, Charles J. Guiteau, who

twice fired his 0.44-caliber revolver at close range.1 The

first shot grazed the President’s right arm, whereas the second entered his back between the 11th and 12th ribs, four

inches to the right of the vertebral column. The President

immediately fell to the ground, ‘‘blood streaming from

his two wounds.’’2 Meanwhile, Blaine and two local police

officers tackled Guiteau as he attempted to escape through a

nearby exit.2

Within minutes, a throng of people surrounded the

President. The first physician on the scene was the District

Health Officer, Dr. Smith Townsend, who discovered Garfield ‘‘apparently dying,’’ the floor ‘‘covered in blood.’’2 The

President remained conscious, immediately complaining of

Assassination Attempt

On the morning of July 2, 1881, James A. Garfield was

en route to his 25th reunion at Williams College. The

President was accompanied by the Secretary of State,

James G. Blaine, with plans to board the 9 AM train for

Massachusetts from the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad

Station in downtown Washington, DC. Shortly after

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-604-356-9953; fax: 11-604-8754036.

E-mail address: sjoharifard@gmail.com

Manuscript received August 23, 2012; revised manuscript December

10, 2012

0002-9610/$ - see front matter Ó 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.02.007

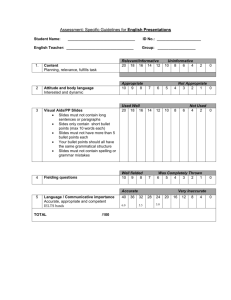

James A. Garfield, circa 1881.

614

severe pain in his back and weakness in his legs.3 Based on

the autopsy findings, this was likely related to the bullet traversing the L1 vertebral body.4 The path of the bullet through

L1 would not necessarily have resulted in paralysis but certainly could have created edema around the spinal cord,

leading to the neurologic symptoms reported.

Dr. Townsend ordered Garfield to be moved to the second

floor of the train station on a mattress, where Drs. D.W. Bliss

and Robert Reyburn, two prominent local physicians, ultimately received him. Dr. Bliss, finding the patient ‘‘deathly

pale, almost pulseless and apparently dying of internal

hemorrhage,’’ proceeded to examine the flank wound, first

with his finger and then with a Nélaton probe.2,5 Although

this unsterile examination of the wound may be surprising

to today’s readers, probing wounds was considered the standard of care for gunshot injuries in the 19th century. Given

that bullet wounds are all contaminated by pieces of clothing

and other foreign bodies, the use of a finger or probe to examine these wounds was thought to be of great benefit and

little harm in the 1880s.6 The bullet was often a nidus for infection, and, thus, early removal was generally considered

therapeutic. Furthermore, at a time when x-ray technology

was in its infancy, fingers and probes were the sole tools at

the physician’s disposal to define the course of the bullet

and, therefore, the patient’s prognosis.

Based on their initial probing of the wound, Garfield’s

physicians assumed that the second bullet had lodged in the

peritoneal cavity, possibly after passing through the liver.

Performing an exploratory laparotomy in the case of

abdominal trauma was an extremely controversial notion

in 1881; in fact, the procedure was not widely accepted as a

viable treatment option for penetrating abdominal trauma

until the turn of the century.7 As such, Garfield’s physicians

had little option but to follow the standard of care of the era

and treat the President with nonoperative management.

Thus, Garfield was moved to the White House via ambulance, where he was fully expected to die overnight. The

President’s staff sent a telegraph to summon Mrs. Garfield,

who was recovering from a bout of malaria on the New Jersey coast.8 Upon arriving at the White House, the First

Lady was given a private audience with her husband to

say her goodbyes.9

To the surprise of his doctors, however, Garfield

survived the night and began a slow recovery. As the

autopsy showed, after traversing L1, the bullet injured the

splenic artery near its takeoff from the celiac axis.4 Remarkably, the President did not bleed to death despite

this life-threatening arterial injury. Instead, a pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery formed as the bleeding stopped,

aided by the tamponade effect of the retroperitoneum.4

In the ensuing 80 days, the President’s medical care

captured the attention of the nation. Garfield’s physicians

issued daily bulletins on their patient’s condition, while

newspapers and medical journals published regular commentary from physicians around the world debating the

likely course of the bullet and the President’s chance of

surviving.

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 4, October 2013

The President’s Physicians

Garfield was cared for by some of the best trauma

surgeons of the era. David Hayes Agnew, the senior-most

consultant attending to the President, was perhaps the most

prodigious surgeon of his day, possessing extensive Civil

War experience in the treatment of gunshot wounds. He

was a Professor of Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine from 1863 to 1884 and served as

President of the American Surgical Association in 1887.10

Agnew’s most important textbook, The Principles and

Practice of Surgery (1878 to 1883), was the authoritative

surgical text of its day.11

Doctor Willard Bliss (Doctor was his first name) was

one of the most prominent physicians in the nation’s capital

in 1881. Bliss received his medical training at the

Cleveland Medical College and was considered an expert

in ballistics, also because of his considerable Civil War

experience. Additionally, he was appointed the head of

Washington, DC’s Armory Square Hospital after the war.

Interestingly, Garfield was not the first President that Bliss

attended to; he treated Zachary Taylor, the 12th President of

the United States, in 1844 for malaria.12

Robert Reyburn was also a prominent medical figure in

Washington, DC in the 1880s. He received his medical

degree from the Philadelphia College of Medicine and

Surgery in 1856. Dr. Reyburn was subsequently appointed

one of the first five faculty members at Howard University’s

School of Medicine and served as Dean from 1870 to

1871.13

Lastly, Joseph Janvier Woodward was a Civil War

surgeon who performed the autopsy of both Abraham

Lincoln and John Wilkes Booth. He consulted in the care of

Garfield and assisted in his autopsy.14

The President’s Clinical Course

In the days immediately after the shooting, Garfield’s

physicians remained preoccupied with determining the path

of the bullet. The wound was probed on multiple occasions,

but contrary to what previous historians have argued, this

was not done with ‘‘unwashed and manure-tainted

hands.’’15 Rather, as Dr. Reyburn indicates in his day-today account of the President’s illness, Garfield’s physicians

made a concerted effort to adhere to Lister’s emerging theories of antisepsis. ‘‘The most scrupulous cleanliness of the

instruments and surgical appliances was observed, and also

of the antiseptic solutions used for the daily washing out of

the wound, and every effort was made to render them as antiseptic as possible.’’2,16 Regardless, the frequent probing of

the wound yielded no concrete information about the bullet’s path. Even Alexander Graham Bell, with his prototype

metal detector, was twice unsuccessful in locating the

bullet.17

Over the next two weeks, the President’s condition

gradually improved. Acknowledging that they might never

T.N. Pappas and S. Joharifard

Did James A. Garfield die of cholecystitis?

determine the exact location of the bullet, but assuming that

it had lodged in the pelvis after traversing the peritoneum,

Garfield’s physicians focused their attention on caring for

his back wound with twice daily dressing changes. Initially,

Garfield suffered from nightly fevers and frequent emesis,

but by day 14, he was eating solid food and appeared to be

convalescing.18 However, by the beginning of the third

week, the President showed signs of a brewing infection.

Surmising that Garfield’s deterioration was caused by secondary infection of the back wound, his physicians responded in kind by debriding the wound, making counter

incisions, and inserting multiple tubes to optimize drainage.2 Surprisingly, as the appearance of the wound improved, Garfield’s overall condition worsened.

The autopsy showed that the aggressive local management of the bullet entry wound resulted in a cavity extending

to the ipsilateral anterior iliac crest. Previous authors have

suggested that this largely iatrogenic cavity was the source of

the President’s sepsis and gradual decline.19,20 In actuality,

however, there is no evidence in the postmortem examination

that the back wound was a source of sepsis. On the contrary, it

appeared to be a very large but well-drained space. There was

no infection under pressure, no residual abscess, and ‘‘very

little pus’’ per the autopsy report.4 Garfield’s physicians irrigated the wound on a daily basis with carbolic acid, a common cleansing solution in the day, via a small rubber

catheter that they inserted directly into the wound. In addition, the President’s surgeons conducted at least two formal

incision and drainage procedures to be certain that the space

was adequately drained.2 Therefore, given the historical clinical data and the autopsy results, one must conclude that although Garfield’s physicians were incorrect in assuming that

the back wound was the cause of the President’s decline, their

management effectively eliminated it as an ongoing source

of sepsis.

Three to four weeks after the shooting, the President

starting eating less, developed abdominal pain, and once

again became regularly febrile. By the sixth week, the

President was clearly septic, ultimately developing parotitis

on day 47 and pneumonia on day 72. If not the back wound,

what then was the cause of the President’s abdominal pain

and delayed sepsis? The answer lies in the postmortem

examination, which describes a bile-filled abscess involving

the gallbladder. Although the autopsy report does not

mention the presence or absence of gallstones and although

there was no histologic examination of the gallbladder, the

presence of a bile-filled abscess adherent to the gallbladder

most likely represents a complication of acute cholecystitis.

An untreated, contained perforation of the gallbladder from

cholecystitis would certainly result in a continued downhill

course associated with fever, malaise, decreased appetite,

abdominal pain, and ultimately sepsis.

Death and Autopsy

On September 17th, the President became febrile, tachycardic to 120 bpm, and complained of severe pain in his

615

anterior mediastinum. Then, late in the evening on September 19th, 80 days after being shot, Garfield suffered a

severe episode of chest pain and died shortly thereafter at

10:35 PM.2 As described in detail below, the postmortem examination showed that the President’s final cause of death

was bleeding secondary to the late rupture of a traumatic

pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery.4 The chest pain experienced two days earlier likely represents a sentinel hemorrhage before the final rupture of the pseudoaneurysm;

although the sentinel hemorrhage may have initially been

contained in the retroperitoneum, the autopsy shows that

rupture of the pseudoaneurysm eventually resulted in free

intraperitoneal hemorrhage and death.4

The postmortem examination was conducted 18 hours

after the President’s death by Drs. Bliss, Reyburn, Agnew,

and Woodward, in addition to other members of the

medical team.4 On external examination, the physicians

commented on the President’s severely emaciated state

and his extensive peripheral wasting. They also noted an ulceration behind his right ear in addition to multiple purpuric macules and pus-filled pustules covering the deceased’s

back, shoulders, axillae, and buttocks.

Early in the course of the autopsy, a flexible catheter was

inserted into the back wound, the purpose of which was to

define the bullet tract from the outside. Garfield’s physicians assumed that when they exposed the abdomen the

catheter would be visible in the peritoneal cavity, most

likely in the pelvis; however, when the abdominal contents

were explored, it became obvious that the bullet had never

entered the peritoneum. Rather than finding the bullet upon

exposure of the abdomen, Garfield’s physicians discovered

extensive adhesions, particularly between the transverse

colon and the anterior edge of the liver. In the left upper

quadrant, they discovered a ‘‘mass of black, coagulated

blood that covered and concealed the spleen and the left

margin of the greater omentum.’’4 When they pulled back

the omentum, they saw that the blood tracked down into

the pelvis where ‘‘more than a pint of bloody fluid’’ was

found.4

At this juncture, the medical team concluded that the

President died from secondary hemorrhage, the source of

which was yet undiscovered. Only after removing the

abdominal organs and engaging in detailed dissection did

the examiners find ‘‘a rent, nearly four-tenths of an inch

long in the main trunk of the splenic artery, two inches and

a half to the left of the coeliac axis.’’4 Together these findings led Garfield’s physicians to determine that the President’s proximate cause of death was a late rupture of a

traumatic splenic artery pseudoaneurysm. ‘‘This hemorrhage,’’ they wrote in a bulletin that was reproduced in

The New York Times, ‘‘is believed to have been the cause

of the severe pain in the lower part of the chest complained

of just before death.’’4

A good part of the remainder of the autopsy was focused

on determining the path of the bullet. Tracing the catheter

inserted before making the initial incision, Garfield’s

physicians found an iatrogenic tract leading down from

616

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 4, October 2013

the wound, behind the right kidney, along the iliac fascia,

and almost into the right groin. On the other hand, the

original bullet tract was ‘‘completely obliterated by the

healing process’’ and therefore had to be dissected in order

to decipher the ultimate path of the bullet.4 Much to their

surprise, Garfield’s physicians soon discovered that the bullet was encysted below the pancreas, not in the pelvis as

they had thought:

It was found that from the point at which it had fractured

the right eleventh rib (three inches and a half to the right

of the vertebral spines) the missile had gone to the left

obliquely forward, passing through the body of the first

lumbar vertebra, and lodging in the adipose connective

tissue immediately below the lower border of the

pancreas, about two inches and a half to the left of the

spinal column and behind the peritoneum.4

After discovering that the bullet tract was ‘‘almost free

of pus,’’ and thus an unlikely source of infection, Garfield’s

medical team was forced to look elsewhere for the source

of the President’s septic condition.4 Although there was

certainly evidence of a congestive pneumonia in the right

lung, Garfield did not complain of cough until very late

in his postinjury clinical course. Moreover, the parotitis

and disseminated pustules appeared after the commencement of fever and rigors. Upon completing the autopsy,

Garfield’s physicians opined that the ‘‘fractured, spongy tissue of the vertebrae furnish[ed] a sufficient explanation of

the septic condition which existed.’’4 In arriving at this conclusion, however, the President’s medical team overlooked

a major unexpected finding of the autopsydthe discovery

of a large abdominal abscess. The original description of

this finding merits inclusion in its entirety:

The abdominal viscera was then carefully removed from

the body, placed in suitable vessels, and examined

seriatim, with the following result: The adhesions

between the liver and the transverse colon proved to

be [be] bound [by an] abscess cavity between the

undersurface of the liver, the transverse colon, and the

transverse [mesocolon], which involved the gallbladder,

and extended to about the same distance on each side of

it, measuring 6 inches transversely and 4 inches from

before backward. This cavity was lined by a thick

pyogenic membrane, which completely replaced the

capsule of that part of the under surface of the liver

occupied by the abscess. It contained about two ounces

of greenish yellow fluidda mixture of pus and biliary

matter. This abscess did not involve any portion of the

substance of the liver except the surface with which it

was in contact, and no communication could be detected

between it and any part of the wound.4

The location of the abscess between the liver and the

transverse colon, combined with the fact that it was reportedly filled with ‘‘greenish yellow fluid,’’ points toward a

perforation of the gallbladder.4 An alternate explanation of

the pericholecystic fluid collection is that it was an abdominal abscess caused by hematologic seeding of the peritoneal

cavity from the infected back wound. This interpretation,

however, does not explain the presence of bile in the abscess.

Furthermore, the autopsy report states that the bullet did not

pass anywhere near the liver or gallbladder, while later

clearly indicating that there was no connection between

the abscess and the back wound. Therefore, the only explanation that seems probable is that the abscess formed because of the perforation of the President’s gallbladder three

to four weeks after he was shot. Moreover, this gallbladder

abscess was the most logical source of the President’s sepsis,

which was, in turn, the cause of Garfield’s unrelenting downhill course.

Why Did Garfield’s Physicians Miss the

Significance of the Gallbladder-Associated

Abscess?

The simplest answer is that Garfield’s physicians may not

have previously seen autopsy evidence of cholecystitis, nor

would they have expected to discover this pathology in an

abdominal gunshot victim. Although reports of cholecystitis

after the treatment of non-gallbladder disease first emerged

in 1844, the disease process was not well characterized until

Frank Glenn’s treatise on the subject presented at the

American Surgical Association in 1947.21–23 Furthermore,

the association between post-traumatic conditions and acalculous cholecystitis was not well documented until 1970,

when Lindberg and Grinnan24 reported their experience

with 12 American Vietnam War soldiers who developed cholecystitis within 10 to 35 days after the management of their

war injuries. Given the somewhat recent delineation of the

pathophysiology behind the development of cholecystitis

in the context of treatment of non-gallbladder disease, it is

not surprising that Garfield’s physicians not only failed to

recognize that the President had developed cholecystitis during his recovery from the shooting but also failed to recognize the significance of the gallbladder abscess they

encountered during the postmortem examination.

Why Did Garfield’s Historians Miss the

Significance of the Gallbladder-Associated

Abscess?

The reason why historians have failed to recognize the

significance of the four by six inch abscess discovered

during the President’s postmortem examination is harder to

delineate. Perhaps the failure of Garfield’s medical team to

recognize the importance of this critical autopsy finding has

led historians to similarly choose to look beyond the

obvious. In addition, it has always been convenient to

accuse the President’s doctors of malpractice, suggesting

that Garfield’s demise was secondary to iatrogenic sepsis

from repeated probing of the bullet wound. This allegation

is made ever so more enticing given that it was mimed by

Guiteau at his trial; when asked why he killed the President,

T.N. Pappas and S. Joharifard

Did James A. Garfield die of cholecystitis?

the assassin replied, ‘‘I simply shot him, it was the doctors

that killed him.’’25

Everyone from Alexander Graham Bell to David

Hayes Agnew had an opinion about the President’s

declining health during his postshooting clinical course.

There was speculation from a variety of sources that

Garfield’s physicians were at best in disagreement and at

worst incompetent. One of the main conclusions of the

autopsydnamely the fact that the President’s doctors had

completely misjudged the bullet tractdseemed to support

the contention that Garfield’s medical team had been

mistaken in their approach. Although the presumption of

intraperitoneal injury certainly colored much of the

medical team’s thinking and care, it is not clear that

Garfield’s physicians would have managed the case

differently had they known that the bullet tracked toward

the President’s left side extraperitoneally through the L1

vertebra. As the pre-eminent surgeon J. Marion Sims so

eloquently argued after Garfield’s death, the President’s

physicians adhered strictly to the standard of care of

the time:

But if the course of the ball could have been ascertained,

the result would have been precisely the same. The

surgeons could only have kept the pus pouch between

the fractured ribs and spine, and the one extending down

into the pelvis, empty and clean. This they did all the

time as the history of the case and the autopsy show.26

Furthermore, even if Garfield’s physicians had possessed the means to ascertain that the President had

developed an abscess around his gallbladder, it seems

highly unlikely that they could have intervened. The first

reports of a cholecystotomy and cholecystostomy had

only recently been published in 1866 and 1878, respectively.27–29 The first successful cholecystectomy, moreover, was not reported by Langenbuch until the year

after the President’s death.30,31

Comments

Most contemporary authors have chosen to take the

obvious errors in diagnosis that were unveiled by the

autopsy as proof that Garfield’s physicians committed gross

negligence.19,20 Although the postmortem examination

made it abundantly clear that the President’s proximate

cause of death was a ruptured pseudoaneurysm, many historians are happy to continue to place all responsibility on

Garfield’s physicians. Why some historians have been unwilling to distribute the responsibility for the President’s

death at least partially on the assassin is unclear; perhaps

it makes for better historical reading to blame the doctors

and not the individual who was holding the gun.

Still, one cannot ignore the unexpected discovery of

a gallbladder-related abscess. Placing this autopsy

finding in context with the patient’s overall clinical

course leads the reader to two plausible conclusions.

First, President Garfield died of a ruptured

617

pseudoaneurysm of the splenic artery, a complication

of the initial gunshot wound. Second, the President’s

clinical course, highlighted by recurrent episodes of

anorexia, extreme weight loss, recurrent fevers, abdominal pain, and small subcutaneous abscesses, was not

caused by an infected bullet tract but was more likely

secondary to complications of an undiagnosed and

unmanaged course of cholecystitis.

References

1. Mr. Blaine’s story of it: what the Premier saw of the assassination of

Mr. Garfield. Washington Post; July 3, 1881:1.

2. Reyburn R. Clinical history of the case of President James Abram Garfield. JAMA 1894;XXII: 411–7; 460–4; 498–502; 545–9; 578–82;

621–4; 664–9.

3. Hamilton FH. A Review of the late President Garfield’s Case. Br Med

J 1881;2:619–20.

4. Verdict of the surgeons: the autopsy on the remains of President Garfield. New York Times; October 2, 1881:1–1.

5. Nélaton M. New methods of discovering the presence of a ball or other

metallic body within a wound-Nelaton’s porcelain probe-Favre’s galvanic probe. Am J Med Sci 1863;45:499.

6. Longmore T. Remarks on the Instruments Designed for Exploring

Gun-Shot Wounds, with a View to Detect Bullets or Other Foreign Bodies Suspected to be Lodged in them. Br Med J 1871;

2:751–2.

7. Nancrede CB. I. Should Laparotomy be Done for Penetrating Gunshot

Wounds of the Abdomen, Involving he Viscera. Ann Surgery 1887;5:

465–90.

8. Sending for Mrs. Garfield: receiving the sad news with fortitude. New

York Times; July 3, 1881:7.

9. Condition of the President at one o’clock Sunday morning. Baltimore

Sun; July 4, 1881:5.

10. Dr. Hayes Agnew dead: the great surgeon yields to an attack of bronchitis. Washington Post; March 23, 1892:4.

11. Agnew DH. The Principles and Practice of Surgery. J.B. Lippincott

and Co., Philadelphia, USA. 1883.

12. Garfield’s doctor dead. Chicago Daily Tribune; February 22,

1889:3.

13. Dr. Reyburn’s death puts Howard in gloom. Baltimore Afro-American;

April 3, 1909:1.

14. Death of surgeon Woodward. Baltimore Sun; August 19, 1884:1.

15. Herr HW. Ignorance is bliss: the Listerian revolution and education of

American surgeons. J Urol 2007;177:457–60.

16. Lister JB. Antiseptic Principle in the Practice of Surgery. Br Med J

September 21, 1867.

17. Yesterday: the bullet finder. Chicago Tribune; August 2, 1881:1.

18. The White House patient: President Garfield’s continued improvement. New York Times; July 16, 1881.

19. Rutkow IM. James A. Garfield. New York, New York, USA: Macmillan; 2006.

20. Millard C. Destiny of the Republic. New York, New York, USA: Doubleday; 2011.

21. Duncan J. Femoral hernial; gangrene of the gallbladder; extravasation

of bile; peritonitis; death. North J Med 1844;2:1151–3.

22. Glenn F. Acute cholecystitis following the surgical treatment of unrelated disease. Ann Surg 1947;126:4.

23. Glenn F, Moore S. Gangrene and perforation of the wall of

the gallbladder: a sequela of acute cholecystitis. Arch Surg

1942;44:4.

24. Lindberg EF, Grinnan GL. Acalculous cholecystitis in Viet Nam casualties. Ann Surg 1970;17:152–7.

25. Assassin and avenger: the trial of Guiteau and his alleged assailant.

Washington Post; November 21, 1881:1.

618

26. Hammond WA, Ashhurst J, Sims JM, et al. The surgical treatment of

President Garfield. North Am Rev 1881;133:578–610.

27. Bobbs JS. Case of lithotomy of the gallbladder. Trans Indiana Med Soc

1866;18:68.

28. Alvarez WCW. Dr. Bobbs’ first operation for drainage of a diseased

gallbladder. Gastroenterology 1970;58:128–9.

The American Journal of Surgery, Vol 206, No 4, October 2013

29. Sims JM. Remarks on cholecystotomy in dropsy of the gall-bladder.

BMJ 1878;1:811–5.

30. Langenbach CJA. Ein Fall von Exstirpation der Gallenblasewegen Chronischer Cholelithiasip Heilung. Berliner Klin Wochenschr 1882;19:725–7.

31. Traverso LW. Carl Langenbuch and the first cholecystectomy. Am J

Surg 1976;132:81–2.