- The American School of Classical Studies at Athens

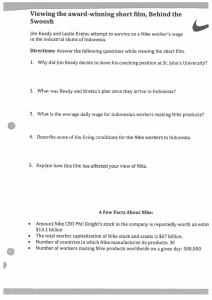

advertisement