Sources of Mental Contamination: Comparing the Effects of Self

advertisement

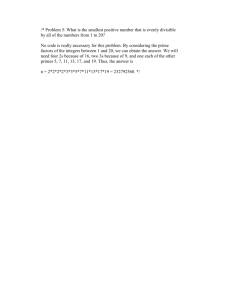

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36, 194–206 (2000) doi:10.1006/jesp.1999.1415, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on Sources of Mental Contamination: Comparing the Effects of Self-Generated versus Externally Provided Primes Thomas Mussweiler and Roland Neumann Universität Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany Received February 18, 1999; revised October 12, 1999; accepted October 12, 1999 Social cognition research has closely examined the processes that are involved in the correction for contaminating influences on judgment. Little is known, however, about how a contaminating influence is detected in the first place. To remedy this shortcoming, we propose a source-monitoring perspective on the detection of bias. This framework suggests that contamination is more likely to occur if its source is similar to the target source. Because judgment processes often involve elaborate internal processing of information, knowledge that is internally generated rather than externally provided is less likely to be seen as contaminating. As a consequence, judgments are more likely to be consistent with the implications of internally generated than externally provided knowledge. The results of two studies using different self-generation procedures (i.e., generating antonyms and solving anagrams) are consistent with this prediction. They demonstrate that in a blatant priming paradigm, judges only correct for the influence of externally provided primes (which yields contrast) but not self-generated primes (which yields assimilation). The implications of these findings are discussed in light of the literature on knowledgeaccessibility effects, source monitoring, and judgmental correction. r 2000 Academic Press Key Words: self-generation; priming; source monitoring; correction. Most judgments are too complex to allow for an exhaustive search of relevant information. Consequently, judges often rely primarily on information that comes to mind easily while making the judgment. Such accessible knowledge is typically used as a judgmental basis, so that the critical judgment is assimilated toward its implications. In order to be used as a judgmental basis, however, easily accessible information has to be seen as relevant for the critical judgment (see The present research was facilitated by a research grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. We thank Galen V. Bodenhausen, Fritz Strack, and R. S. Wyer, Jr., for elaborate discussions of the issue. Thanks also go to Iris Müller for her help in preparing the stimulus material and to Simon Finkeldei, Cornelia Florig, and Daniela Meiser for their help in collecting the data. Address correspondence and reprint requests to Thomas Mussweiler, Psychologie II, Universität Würzburg, Röntgenring 10, 97070 Würzburg, Germany. E-mail: mussweiler@psychologie.uniwuerzburg.de. 194 0022-1031/00 $35.00 Copyright r 2000 by Academic Press All rights of reproduction in any form reserved. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn No. of Pages—13 First page no.—194 Last page no.—206 195 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING Higgins, 1996; Strack, 1992). If this is not the case, judges may forgo the use of accessible knowledge and try to correct for its potentially contaminating influence (Wilson & Brekke, 1994). The typical consequence of such a correction is that the judgment is contrasted away from the implications of accessible knowledge (Martin & Achee, 1992; Schwarz & Bless, 1992; Strack, 1992). Thus, whether judgments are assimilated toward or contrasted away from the implications of accessible knowledge critically depends on what is seen as the cause of accessibility. Before participants can use accessible knowledge to generate a specific judgment, they have to identify the source of accessibility and determine whether it is best attributed to the judgmental target itself or to a potentially contaminating factor. Given that the accessibility of a given construct can be increased by a multitude of situational (e.g., priming; Higgins, Rholes, & Jones, 1977; Srull & Wyer, 1979) and personal factors (e.g., chronic accessibility; Bargh, Bond, Lombardi, & Tota, 1986) this task of source identification is, in fact, difficult to master. Clearly, correctly identifying the source of accessibility is a crucial prerequisite for accurate judgment. In fact, it has been suggested that many instances of judgmental contamination (e.g., halo effects, mood-as-information effects) can be traced back to source confusion (Wilson & Brekke, 1994). How, then, do people differentiate between different sources of accessibility? How do they determine whether the accessibility of information can be attributed to the judgmental target or to a contaminating factor? Or, more generally speaking, how do they detect a potential contamination or bias? To answer these questions, it may be useful to apply insights into the general mechanisms that underlie the identification of the sources of cognitive outcomes (e.g., Johnson, Hashtroudi, & Lindsay, 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981) to the realm of knowledge accessibility and judgmental contamination. SOURCE MONITORING AND THE DETECTION OF BIAS The cognitive literature on source monitoring (for an overview, see Johnson et al., 1993) has identified a number of factors that promote and hinder the accurate identification of the source of a given memory. According to Johnson and colleagues (e.g., Johnson et al., 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981), source-monitoring judgments are based on those characteristics that are typically associated with a memory stemming from a particular source. For example, a person who is trying to identify whether a particular memory is based on external input (e.g., a perceptual experience) or internal generation (e.g., thought and imagination) may search for those characteristics that are typically associated with these two types of memories. Because memories originating in external input typically include more perceptual and contextual information than internally generated memories, a specific memory is likely to stem from external input if it includes a lot of these details. Internally generated memories, on the other hand, typically include more information about the kinds of mental operations that produced them. Thus, a specific memory that includes a great deal of information about such operations is jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 196 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN likely to be seen as internally generated. From this perspective, the accuracy of a source-monitoring judgment critically depends on the amount of overlap between the characteristics of the critical sources. The more two sources produce memorial consequences that are clearly distinguishable, the easier it is to attribute a given memory to one of them. The more similar these consequences are, however, the more difficult source identification becomes and the more likely source confusion errors are to occur. What are the implications of this framework for the realm of knowledge accessibility and judgment contamination? How do the principles that appear to guide the identification of the source of a memory relate to the identification of the source of accessibility? The source-monitoring perspective suggests that in order to determine whether a particular concept came to mind because of the judgmental target itself or because of an extraneous factor, judges search for characteristics that are typically associated with both sources. For example, judges who recall that the word ‘‘adventurous’’ was part of a scrambled sentence (Srull & Wyer, 1979) which they unscrambled right before reading about an ambiguously described target person (‘‘Donald’’) are likely to attribute accessibility to a contaminating factor and may try to correct for its potential influence (Strack, Schwarz, Bless, Kübler, & Wänke, 1993). Judges who recall how they extracted the notion that Donald is adventurous from the target description, on the other hand, are likely to attribute the accessibility of this concept to the judgmental target itself and may readily use it to characterize Donald. To the extent that both sources are clearly distinguishable, source identification is likely to be easy and accurate. The more accessibility stemming from a contaminating source and the target source (i.e., the judgmental target) are characterized by similar properties, however, the more difficult and error prone the source identification process becomes and the more likely source confusion is to occur. This suggests that judges should be more likely to see accessible knowledge as contaminating and try to correct for its influence if the source of accessibility is clearly distinguishable from the judgmental target. The priming literature (for a recent review, see Higgins, 1996) is well consistent with this assumption. It has repeatedly been demonstrated that judgments are more likely to be contrasted away from the implications of accessible knowledge if the source of accessibility is clearly distinguishable from the judgmental target. For example, awareness of the priming event (e.g., Lombardi, Higgins, & Bargh, 1987; Strack et al., 1993) critically determines whether assimilation or contrast occurs. If participants are unaware of the priming event (i.e., the source of accessibility is indistinguishable from the judgmental target), judgments are typically assimilated to the primes. Thus, if a subtle priming procedure is used (Higgins et al., 1977; Srull & Wyer, 1979, 1980), participants are unlikely to be aware of the fact that a specific trait category comes to mind because it has been activated in the preceding priming task (i.e., that accessibility stems from a contaminating source). As a consequence, judgments will be based on the implications of accessible knowledge which leads to assimilation. If, jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 197 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING however, judges are aware of the priming episode and can thus distinguish the source of accessibility from the judgmental target, contrast is more likely to occur (Strack et al., 1993). Thus, blatant priming (Martin, 1986; Martin et al., 1990) typically induces participants to contrast their judgments away from the implications of the primed concept. This may be the case because with blatant priming, the source of accessibility is easier to distinguish from the judgmental target so that judges may deliberately try to correct for its potentially contaminating influence. INTERNAL VERSUS EXTERNAL SOURCES OF ACCESSIBILITY One factor that is likely to influence the degree to which a contaminating source of accessibility is distinguishable from the target source is whether the contaminating source is external or internal in nature. As we have pointed out before, the source-monitoring framework (Johnson et al., 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981) suggests that the less overlap in characteristics two sources have, the easier they are to distinguish and the less likely source confusion is to occur. In many judgment situations, however, external sources of accessibility share less properties with the target source than internal sources and should thus be easier to distinguish. To see this, it is important to specify the properties that characterize the target source in social judgment in general and judgmental priming paradigms in particular. One crucial characteristic here is that accessibility stemming from the judgmental target itself is likely to be the result of an internal generation process. Because explicit characterizations (e.g., ‘‘Donald is adventurous’’) are typically not provided, participants have to relate the information that is provided about the target person to their stored knowledge about similar behaviors. That is, they have to engage in elaborate mental operations in order to judge the target person. Given the general properties of external and internal sources (Johnson et al., 1993), accessibility stemming from the target source is thus likely to be characterized by a lot of detail about mental operations and very little perceptual and contextual detail. In this respect, it contrasts well with accessibility stemming from an external contaminating source, which is likely to be characterized by a lot of perceptual and contextual detail and little detail about mental operations. For example, in the standard priming paradigm, participants may still remember the context in which a prime was presented (e.g., the scrambled sentence; Srull & Wyer, 1979) or the font in which it was printed. Because such details are unlikely to result from the internal generation process that is responsible for increased levels of accessibility stemming from the target source, they help to distinguish accessibility stemming from an external contaminating source from that produced by the target source. Internal contaminating sources, however, do not produce such differentiating perceptual and contextual detail. Rather, they are likely to be characterized by the same kind of details about mental operations as the target source. In tandem, this lack of distinguishing properties (i.e., perceptual and contextual detail) and presence of shared properties (i.e., detail about mental jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 198 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN operations) renders source identification more difficult. As a consequence, judges are more likely to attribute the accessibility stemming from an internal contaminating source to the judgmental target. Consistent with this contention, recent research examining the role of source monitoring in cryptomnesia (i.e., false beliefs in the originality of one’s ideas; Landau & Marsh, 1997) has demonstrated that source confusion is more likely to occur, if the two critical sources both involve internal generation processes. In one study (Landau & Marsh, 1997) participants had to list solutions to a word-search puzzle in competition with a computer. After an initial generation phase in which both the participants and the computer listed as many solutions as they could find, participants were instructed to list all the solutions that they themselves had come up with. In this paradigm, giving a solution that was provided by the computer constitutes an instance of source confusion. Thus, in order to provide a correct answer, participants have to distinguish between their own responses and those of the computer. For some of the participants, distinguishing between the external contaminating source (i.e., the computer) and the internal target source (i.e., the self) was complicated by requiring them to anticipate what solution the computer would come up with. Doing so adds an aspect of self-generation to the computergenerated solutions and thus renders them more similar to the self-generated solutions. As a consequence, participants who anticipated the computer-generated solutions should show more signs of source confusion. In fact, this is exactly what Landau and Marsh (1997) found: Anticipating the computer-generated solutions induced participants to mistake more of these solutions as their own. These findings indicate that it may be more difficult to distinguish the cognitive consequences of a contaminating source from those of the target source, if both include self-generation processes. Applied to the realm of knowledge-accessibility effects, these findings suggest that accessibility stemming from an internal contaminating source may be more likely to be attributed to the target source than accessibility stemming from an external source. Recent research on knowledge-accessibility effects outside of the standard priming paradigm provides initial support for this assumption. In particular, it has been demonstrated (Mussweiler & Strack, 1999) that the self-generation of judgment-relevant knowledge contributes to the assimilative effects of judgmental anchoring (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974)—the assimilation of a numeric estimate to a previously considered standard. PRESENT RESEARCH Consistent with our theoretical argument, these findings suggest that an internal contaminating source may be more difficult to distinguish from a primarily internal target source than an external contaminating source. For the realm of knowledge-accessibility effects and judgment contamination, this suggests that judges may be less likely to correct for the potentially contaminating effects of internally generated knowledge. The present research was designed to test this possibility. To do so, we used a blatant priming paradigm (Martin, 1986; Martin et jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 199 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING al., 1990). For about half of our participants, the prime words were externally provided. Consistent with the standard finding in the blatant priming paradigm, we expected that these participants would contrast their judgments about the target person away from the implications of the primes. This should be the case because accessibility resulting from the external contaminating source should be easy to distinguish from accessibility resulting from the target source, so that participants correct for its assumed influence. The other half of our participants, however, generated the primes themselves. For them, accessibility stemming from the contaminating source and the target source should be more difficult to distinguish. As a consequence, judges are more likely to use knowledge that was rendered accessible by the contaminating source as a basis for their judgment (i.e., they are less likely to correct) so that judgments should be assimilated to the primes. In summary, externally provided blatant primes should yield contrast, whereas self-generated primes should yield assimilation. STUDY 1 In Study 1, participants were blatantly primed with words related to the trait concept of unlikeability or words that are neutral with respect to the likeability dimension. Using a yoked design, half of the participants generated these words themselves by finding antonyms to a list of words associated with likeability, while the other half received words generated by one of the other participants. Subsequently, participants were told to judge the likeability of an ambiguously described target person. To underline that the primed trait words are not relevant for judgments of the target person, both tasks were said to be completely unrelated. Method Participants. Thirty-three nonpsychology students at the University of Würzburg were recruited as participants and randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions. They participated in groups of up to 10 and were offered a chocolate bar as compensation. Materials. During our priming procedure, participants received a list of 15 words under the guise of a pretest for a study on language comprehension. For half of the participants, all 15 words were neutral with respect to the critical likeability dimension (e.g., sleep, heavy). For the other half, 10 of the 15 words were closely associated with likeability (e.g., love, to pet). In the self-generation condition, participants were instructed to list three antonyms for each of the words. It was explained that antonyms are words that are opposite to each other in meaning, so that ‘‘healthy,’’ for example, is an antonym for ‘‘sick.’’ Because the critical target words were closely associated with likeability (e.g., to love), the generated antonyms are likely to be associated with unlikeability, so that the latter trait concept should be primed by our manipulation. Using a yoked design, each participant in the externally provided condition was given the list of the target words and the respective antonyms that were listed by jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 200 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN one of the participants in the self-generation condition. They were instructed to indicate for each of the listed antonyms whether it constitutes a high- or low-frequency word. In sum, the four experimental conditions resulted from an orthogonal combination of the two factors generation (self-generated vs externally provided) and priming (unlikeable vs control). We used a translation of Srull and Wyer’s (1979) ‘‘Donald’’ paragraph as our target description. In this paragraph the target person (‘‘Marcus’’) was described as performing a number of evaluatively ambiguous behaviors (e.g., denying a salesman entry into the flat). Participants judged ‘‘Marcus’’ along 11 9-point rating scales, ranging from ‘‘1’’ (e.g., unlikeable) to ‘‘9’’ (e.g., likeable), one of which pertained to Marcus’ likeability. Procedure. Participants were contacted in the university cafeteria and asked to take part in two psychological experiments. They were guided to a separate room. Upon arrival they were greeted by another experimenter, who handed them a stack of four folders, instructed them to work through these folders in the given order, and to close each of them after completion of the included material. The first folder included general instructions. Here, participants were informed that they were about to take part in two separate studies, one on language comprehension and one on impression formation. It was pointed out that both studies were completely unrelated and were administered together solely for efficiency reasons. To further underline the unrelatedness of both studies, the materials pertaining to each of them were printed in different fonts and on paper with different shades of white. The second folder included the study on ‘‘language comprehension,’’ which contained the priming manipulation. The third folder contained the instructions and the target description for the impression-formation task. Here, participants were first informed that we were interested in how children judge people. To investigate this question, we would first have to find some appropriate target descriptions. Therefore, we would like them to carefully read the following description of a person named ‘‘Marcus’’ and would then asked them to judge this person on a number of personality dimensions. The fourth folder included the central dependent measure, which assessed participants’ judgments about Marcus. After completion of these four folders, participants were debriefed, thanked for their participation, and offered a chocolate bar as compensation. Results Preliminary analysis. To test for the effectiveness of our priming manipulation, we had two independent judges rate how strongly the generated antonyms are associated with likeability. They rated each of the listed antonyms along a 5-point scale ranging from 22 (‘‘extremely unlikeable’’) to 2 (‘‘extremely likeable’’). The individual scores for each of the antonyms were combined into one overall score for each participant. Both judges showed high agreement (r 5 .99), so that their ratings were combined. As expected, the antonyms generated in the unlikeability priming condition proved to be more strongly associated with unlikeability jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 201 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING TABLE 1 Mean Ratings of ‘‘Marcus’ ’’ Likeability by Generation and Priming Generation Priming Externally provided Self-generated Neutral Unlikeable 2.00 3.38 2.38 1.13 Note. Values depict mean ratings on a 9-point rating scale ranging from 1 (‘‘unlikeable’’) to 9 (‘‘likeable’’). The higher the value the higher the judged likeability; N 5 8 for all cells. (M 5 21.21) than those generated in the control condition (M 5 .15), t(14) 5 23.41, p , .001. Thus, our priming manipulation induced participants to generate words associated with unlikeability. Target ratings. Inspection of Table 1 reveals that the judged likeability of the target person ‘‘Marcus’’ depended on the priming and generation conditions.1 Specifically, participants who received externally provided antonyms judged Marcus to be more likeable in the priming condition than in the control condition. Thus, participants in the externally provided condition contrasted their judgments away from the implications of the prime. For participants who generated primes themselves, however, assimilation resulted: They judged Marcus as less likeable in the priming condition than in the control condition. This pattern produced a significant interaction effect in a 2 (self-generated vs externally provided) 3 2 (priming vs control) ANOVA using the likeability ratings as the dependent measure, F(1, 28) 5 4.46, p , .05. An analysis of the individual contrasts further revealed that the difference between the priming and the control condition was marginally significant in both the self-generated condition, t(28) 5 1.75, p , .06 (one-tailed), and the externally provided condition, t(28) 5 1.35, p , .1 (one-tailed). Discussion These findings provide initial support for our predictions. They demonstrate that the direction of the priming influence may depend on whether primes are externally provided or self-generated. As in previous research that used blatant priming (e.g., Martin, 1986; Martin et al., 1990) judgments were contrasted away from the implications of externally provided primes. For self-generated primes, however, this tendency was reversed. Here judgments were assimilated to the implications of the primes. Although this pattern proved to be reliable in the overall ANOVA, the individual contrasts for the assimilation and the contrast effect were not quite significant. Given the small sample size, this is likely to be primarily a problem of statistical power. To remedy this weakness, we used a larger sample in our second experiment. 1 No reliable effects were obtained on the neutral dimensions, all F’s , 1.8, p . .18. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 202 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN A second concern Study 2 was designed to address pertains to a potential ambiguity associated with the self-generation procedure used in Study 1. One may argue that the obtained reversal in the direction of the priming effect may be caused by a specific feature of our procedure rather than the mode of generation of the primes. In particular, participants who generate antonyms (e.g., hate) to the provided target words (e.g., love) may focus on these target words more than participants who simply rated the antonyms generated by another participant. Consequently, the two opposing concepts of ‘‘likeability’’ and ‘‘unlikeability’’ may be primed simultaneously for participants in the self-generated condition: Focusing on the ‘‘likeable’’ target words may prime ‘‘likeability,’’ whereas generating antonyms may prime ‘‘unlikeability.’’ Thus, it is not clear whether the effects we obtained in the self-generation condition represent contrast away from ‘‘likeability’’ or assimilation toward ‘‘unlikeability,’’ as we have assumed. To clarify this ambiguity and provide more unequivocal support for our assumption that self-generated primes produce assimilation, Study 2 used a different selfgeneration procedure. STUDY 2 Specifically, we had participants in the self-generation condition solve a set of 15 anagrams. The solutions to these anagrams were either closely associated with likeability (e.g., love) or not associated with likeability at all (e.g., sleep). Participants in the externally provided condition were provided with the anagrams as well as with their solutions and were instructed to rate how difficult the respective anagrams were. Note that unlike the antonym-generation procedure used in Study 1, this anagram procedure exposes all participants only to the concept of likeability and not to its opposite. Thus, only one concept is primed in both the self-generated and the externally provided conditions. To the extent that the results of Study 1 are not an artifact of the antonym-generation procedure, solving anagrams should produce an assimilation effect, whereas rating their difficulty should yield contrast. Method Participants. Eighty nonpsychology students at the University of Würzburg were recruited as participants and randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions. They participated in groups of up to four and received 16 German Marks (about $9 U.S. at the time) as a compensation. Materials and procedure. Upon arrival in the lab, participants were directed to a separate booth and received a stack of folders similar to the one described in Study 1. The main difference between both studies pertains to the nature of the priming manipulation. Under the guise of a pretest for a study on language comprehension, participants received a list of 15 anagrams. For half of the participants, the solutions to these anagrams were the 15 neutral words used in Study 1. For the other half, they were the 10 words associated with likeability as well as the 5 neutral words used before. In the self-generation condition, jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 203 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING TABLE 2 Mean Ratings of ‘‘Marcus’’’ Likeability by Generation and Priming Generation Priming Externally provided Self-generated Neutral Likeable 2.55 1.98 2.13 3.65 Note. Values represent mean ratings on a 9-point rating scale ranging from 1 (‘‘unlikeable’’/ ‘‘unfriendly’’) to 9 (‘‘likeable’’/‘‘friendly’’). The higher the value the higher the judged likeability; N 5 20 for all cells. participants had to solve the anagrams themselves. We carefully pretested each anagram to ensure that all participants would be able to solve them and that the solutions are indeed identical to the words used in Study 1. Participants in the externally provided condition received the same anagrams along with their respective solutions. They were instructed to indicate whether they see each of the anagrams as easy or difficult to solve. Note that because in contrast to Study 1 this procedure does not expose participants to antonyms for the target words, it primes ‘‘likeability’’ rather than ‘‘unlikeability.’’ In sum, the four experimental conditions resulted from an orthogonal combination of the two factors generation (selfgenerated vs externally provided) and priming (likeable vs control). We used the same target description as in Study 1. After reading this description, participants judged ‘‘Marcus’’ along 11 dimensions. To provide a more sensitive measure as the one used in Study 1, we included two critical dimensions which are both closely associated with likeability. Specifically, participants rated how likeable (1 5 unlikeable, 9 5 likeable) and how friendly (1 5 unfriendly, 9 5 friendly) ‘‘Marcus’’ was. After completion of these questions, participants were thanked, debriefed, and offered their compensation. Results and Discussion Ratings on the two critical dimension were closely related (r 5 .60, p , .001) and thus combined into one likeability score.2 Inspection of Table 2 reveals the same pattern obtained in Study 1. Specifically, participants who received externally provided primes judged Marcus to be less likeable in the priming condition than in the control condition. Thus, they contrasted their evaluations of Marcus away from the implications of the primes. Participants who generated the primes themselves, however, assimilated their judgments about Marcus to the primes, such that they judged Marcus as more likeable in the priming than in the control condition. This pattern produced a significant interaction effect in a 2 (selfgenerated vs externally provided) 3 2 (priming vs control) ANOVA, using the combined likeability score as a dependent measure, F(1, 76) 5 13.17, p , .001. 2 No reliable effects were obtained on the neutral dimensions, all F’s , 1.6, p . .2. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 204 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN An analysis of the individual contrasts further revealed that the difference between the priming and the control condition was significant for self-generated primes, t(76) 5 3.49, p , .001 (one-tailed) and marginally significant for externally provided primes, t(76) 5 1.51, p , .07 (one-tailed). Inspection of the means suggests that the latter contrast may not have obtained significance because of a floor effect: Control participants already judged Marcus extremely negatively, so that it was difficult for the experimental participants to give even lower ratings. Despite this restriction, combining the effects of Studies 1 and 2 (Rosenthal & Rosnow, 1991) reveals that across both studies the contrast effect that resulted from exposure to externally provided primes was reliable, Z 5 1.93, p , .026 (one-tailed).3 Thus, using a self-generation procedure that rules out the alternative explanation outlined before, these findings replicate those of Study 1. GENERAL DISCUSSION In summary, the results of Studies 1 and 2 demonstrate that the direction of a priming influence depends on whether the primes are externally provided or self-generated. Consistent with many other findings (e.g., Martin, 1986; Martin et al., 1990), we found that judgments about an ambiguously described target person are contrasted away from the implications of externally provided primes. In light of current conceptualizations (e.g., Higgins, 1996; Martin & Achee, 1992; Strack, 1992), which assume that such contrast effects are typically caused by judgmental correction, this finding suggests that participants attempted to correct for the influence of externally provided primes. For self-generated primes, however, impressions of the target person were assimilated toward the primes. As pointed out before, here assimilation may prevail because judges fail to correct for the influence of self-generated primes. Specifically, accessibility stemming from an internal contaminating source may be more difficult to distinguish from accessibility stemming from the target itself, so that judges may mistakenly use easily accessible concepts to characterize the target person even if these concepts were rendered accessible by the priming task. The fact that in Study 1 the target evaluations in the self-generated priming condition were extremely negative supports the assumption that self-generation prevented judgmental correction. In particular, the mean judgment for this group (M 5 1.13) was virtually at the negative end point of the provided scale. This suggests that participants did, in fact, not correct their evaluations of the target. Thus, despite the blatantness of the primes, self-generation produced what is typically considered to be the default effect of knowledge accessibility, namely assimilation (cf., Higgins, 1996; Strack, 1992). The current findings are well consistent with previous results demonstrating 3 To combine both analyses, we followed the procedure suggested by Rosenthal and Rosnow (1991). First, we determined the standard normal deviates (Z) for the p values obtained in both studies. These were Z 5 1.25 for Study 1 and Z 5 1.48 for Study 2. Based on these individual Zs, we calculated a combined value of Z 5 1.93, which is significant at p , .026. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 205 SELF-GENERATION AND PRIMING that self-generation contributes to assimilation in other knowledge-accessibility paradigms such as judgmental anchoring (Mussweiler & Strack, 1999) and belief perseverance (Davies, 1997). Taken together, these findings converge on the conclusion that judges are less likely to correct for a potentially contaminating effect of self-generated knowledge. From the current theoretical perspective, this may be the case because accessibility stemming from an internal contaminating source is more difficult to distinguish from accessibility that may rightfully be attributed to the judgmental target. In this respect, self-generation thwarts accurate source monitoring and ultimately impedes attempts to correct for contaminating influences. The present research examined self-generation as one factor that may blur the distinction between accessibility resulting from a contaminating source and the target source. The source-monitoring framework lined out by Johnson and colleagues (e.g., Johnson et al., 1993; Johnson & Raye, 1981), however, suggests many other factors that may have very similar effects. In fact, any factor that renders the identification of the source of accessibility more difficult is likely to produce more source confusion and may thus prevent correction for its influence. For example, because source-monitoring judgments critically depend on how well the respective sources are encoded, putting judges under cognitive load during the priming task may thwart accurate source identification. As a consequence, judgments may be more consistent with the primed concept. Clearly, this possibility—although plausible on theoretical grounds—remains to be tested empirically. CONCLUSION For the past 2 decades, knowledge-accessibility effects have been one of the main foci of social cognition research. Although, elaborate models specifying the judgmental mechanisms that underlie the correction for contaminating influences on knowledge accessibility have been proposed (e.g., Martin & Achee, 1992; Strack, 1992; Wegener & Petty, 1997; Wilson & Brekke, 1994), little is known about how judges detect contamination in the first place. In the present article, we have attempted to present a conceptual framework that may help to answer this question. Specifically, judges may distinguish between a contaminating source and the target source of accessibility much in the same way they distinguish between the sources of other cognitive outcomes. Although this framework remains speculative to some extent and clearly requires more empirical scrutiny, it is quite consistent with the current findings on the consequences of self-generated primes. It may thus prove to be a fruitful starting point for an examination of the psychological processes that underlie the detection of bias in social judgment. REFERENCES Bargh, J. A., Bond, R. N., Lombardi, W., & Tota, M. E. (1986). The additive nature of chronic and temporary sources of construct accessibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 869–878. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn 206 MUSSWEILER AND NEUMANN Davies, M. F. (1997). Belief persistence after evidential discrediting: The impact of generated versus provided explanations on the likelihood of discredited outcomes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 561–578. Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social Psychology: Handbook of basic principles. (pp. 133–168). New York: Guilford. Higgins, E. T., Rholes, W. S., & Jones, C. R. (1977). Category accessibility and impression formation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 141–154. Johnson, M. K., Hashtroudi, S., & Lindsay, D. S. (1993). Source monitoring. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 3–28. Landau, J. D., & Marsh, R. L. (1997). Monitoring source in an unconscious plagiarism paradigm. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 4, 265–270. Lombardi, W. J., Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). The role of consciousness in priming effects on categorization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13, 411–429. Martin, L. L. (1986). Set/reset: Use and disuse of concepts in impression formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(3), 493–504. Martin, L. L., & Achee, J. W. (1992). Beyond accessibility: The role of processing objectives in judgment. In L. L. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), The construction of social judgment (pp. 249–275). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Martin, L. L., Seta, J. J., & Crelia, R. A. (1990). Assimilation and contrast as a function of people’s willingness and ability to expend effort in forming an impression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 27–37. Mussweiler, T., & Strack, F. (1999). Hypothesis-consistent testing and semantic priming in the anchoring paradigm: A selective accessibility model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 136–164. Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1991). Essentials of behavioral research: Methods and data analysis. New York: McGraw–Hill. Schwarz, N., & Bless, H. (1992). Constructing reality and its alternatives: An inclusion/exclusion model of assimilation and contrast effects in social judgment. In H. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), The construction of social judgment (pp. 217–245). Hilldale, NJ: Erlbaum. Srull, T. K., & Wyer, R. S. (1979). The role of category accessibility in the interpretation of information about persons: Some determinants and implications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(10), 1660–1672. Srull, T. K., & Wyer, R. S. (1980). Category accessibility and social perception: Some implications for the study of person memory and interpersonal judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38, 841–856. Strack, F. (1992). The different routes to social judgments: Experiential versus informational strategies. In L. L. Martin & A. Tesser (Eds.), The construction of social judgment (pp. 249–275). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Strack, F., Schwarz, N., Bless, H., Kübler, A., & Wänke, M. (1993). Awareness of the influence as a determinant of assimilation versus contrast. European Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 53–62. Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185, 1124–1130. Wegener, D. T., & Petty, R. E. (1997). The flexible correction model: The role of naive theories of bias in bias correction. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. (Vol. 29). San Diego: Academic Press. Wilson, T. D., & Brekke, N. (1994). Mental contamination and mental correction: unwanted influences on judgments and evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 117–142. jesp 1415 @xyserv1/disk3/CLS_jrnl/GRP_jesp/JOB_jesp36-2/DIV_325a07 dawn