Pre-lecture Notes III.5 – Simple Quasi

advertisement

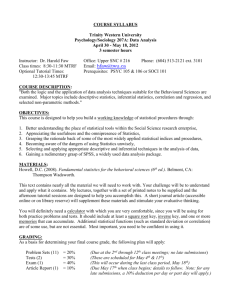

Pre-lecture Notes III.5 – Simple Quasi-Experiments There are two ways to approach quasi-experiments: Why are they not considered “real” experiments? and How are they different from all other correlational studies? But, before taking either of these two approaches, we need to define what they are: Quasi-Experiment – a correlational study involving one very stable subject variable and one labile “data” variable that is analyzed (and interpreted) as if the subject variable had been manipulated (i.e., as if the data came from a between-subjects experiment) An example of a quasi-experiment is when you examine the relationship between gender (i.e., male vs female, which is technically sex, not gender, but I’m too embarrassed to type that word – oh, wait…) and any labile variable, such as current mood, mean response time, asking for directions, etc. You did not manipulate gender – it is not under your complete control – so it isn’t really an independent variable, so this isn’t really a between-subjects experiment, but you act as if it had been manipulated and run an independent-samples t-test to compare the data between males and females, instead of calculating the (point-biserial) correlation between gender and the data variable. Even more important: if you find a significant difference between the two groups, then you conclude that the subject variable caused the difference in the data variable, ignoring the directionality and third-variable problems, as long as all other standard suggestions regarding internal validity were followed (e.g., no experimenter bias while collecting the data, etc.). First, let’s dispense with a certain non-issue that sometimes causes some grief, even among some experts. The fact that the data are analyzed using a t-test instead of a correlation is pretty much irrelevant. The underlying statistics for an independent-samples (between-subjects) t-test and for a point-biserial correlation are absolutely identical. The p-value produced by the two analyses will always be exactly the same, so if one analysis is significant, the other will be, too. There is a simple formula to convert the tstatistic from a t-test to a point-biserial correlation and an equally simple formula to convert a pointbiserial correlation to a t-statistic. They really are the same thing, when you get down to the nuts and bolts. So, you can ignore the type of analysis that is performed. That’s not at all important. Now let’s really compare a quasi-experiment with a true experiment. The key to the latter is that it has an independent variable acting as the potential cause – a variable that the experimenter has complete control over and can manipulate while, hopefully, holding everything else constant or equal or average. A quasiexperiment doesn’t have an independent variable; the subject variable that is taking the place of the IV defines a difference that pre-exists between the two groups of subjects. Why does the issue of manipulated vs pre-existing-difference matter? It matters because, in a real experiment, you take two groups of people that are equal on average in every way and then do a manipulation that creates one and only one difference between them. Therefore, if you find a difference in the data, later, you know what caused the difference: it must be the manipulation because the two groups are otherwise the same on average. In contrast, when the groups are defined in terms of some preexisting difference, such as gender or handedness or birth-order-position, then you have no good reason to assume that the one and only difference between them is the subject variable that you’re interested in. For example, males and females differ (psychologically) in many ways other than the objective, observable differences that define male vs female. Likewise, right- and left-handers differ in ways other than which hand they use to write and/or throw things. And people who were born first rather than later differ in ways other than having no older siblings. In short, when you use a subject variable as an IV there is no way to avoid a whole bunch of confounds. When you compare males to females, the two groups differ in many ways (not all of which directly involve what defines male vs female), so you will not have a clear idea as to what caused any observed difference in the data. The relationship between gender and the data variable, for example, might be spurious; the real cause of the difference between males and females might be something other than gender, itself. Even shorter: a quasi-experiment is an experiment that had very little (if any) internal validity to start with. Now let’s come at this from the opposite direction and ask why quasi-experiments are not just viewed as one of the various types of correlational study. Instead of looking at the subject variable and saying: “that isn’t an independent variable!” let’s look at the subject variable and say: “that’s really a lot more stable than the data variable.” Why does the relative stability of the two variables matter? It matters because it makes certain causal explanations of the entire pattern of data much more or less plausible than others. Recall that the main reason that you can’t take a correlation between X and Y as evidence that X causes Y is that there are two other plausible explanations: Y causes X and/or Z causes both X and Y (which don’t cause each other). These are the directionality and third-variable problems, respectively. Now look at these two alternative explanations for an X-Y correlation under the assumption that X is very stable (e.g., gender) and Y is very labile (e.g., current mood). Ask yourself: is reversed causation (i.e., Y causing X, instead of X causing Y) really plausible? Is it possible for current mood to cause a person to be male or female? I hope/assume that you agree that this is so implausible that we can pretty much ignore it. Great. One alternative down. Now ask yourself: is there some third variable that can cause both X and Y (without there being any causal relationship between X and Y)? Is there something that can both cause a person to be male or female and cause their current mood? Well, in this case the answer is Yes (as I’ll cover in lecture), but it’s so unlikely that it, too, can usually be ignored. Therefore, we’re left with only one viable explanation for the correlation between X (the subject variable) and Y (the data variable) from our quasi-experiment: X (the subject variable) – or something correlated with X (i.e., a confound) – must have caused the difference in Y (the data variable). This is exactly the same as under a between-subjects experiment: the IV (the manipulated variable) – or something correlated with the IV (i.e., a confound) – must have caused the difference in the DV (the data variable). This is why quasi-experiments are called quasi-experiments and are often separated, methodologically, from other correlational studies. When it comes to interpretation, they are more like between-subject experiments than they are like “plain” correlational studies. To be clear: a “plain” correlational study concerns two equally-labile variables, such as depression and anxiety, while a quasi-experiment concerns one very stable variable and one labile variable.