Imagined Portraits: Reviving figures from Australia's past

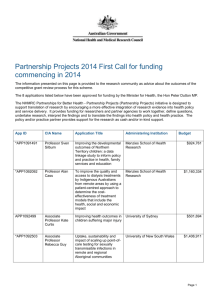

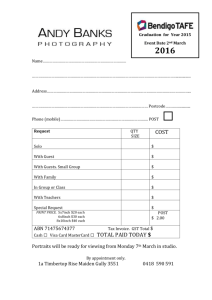

advertisement