Cath Lab Uses “Jumbotron” to Super

advertisement

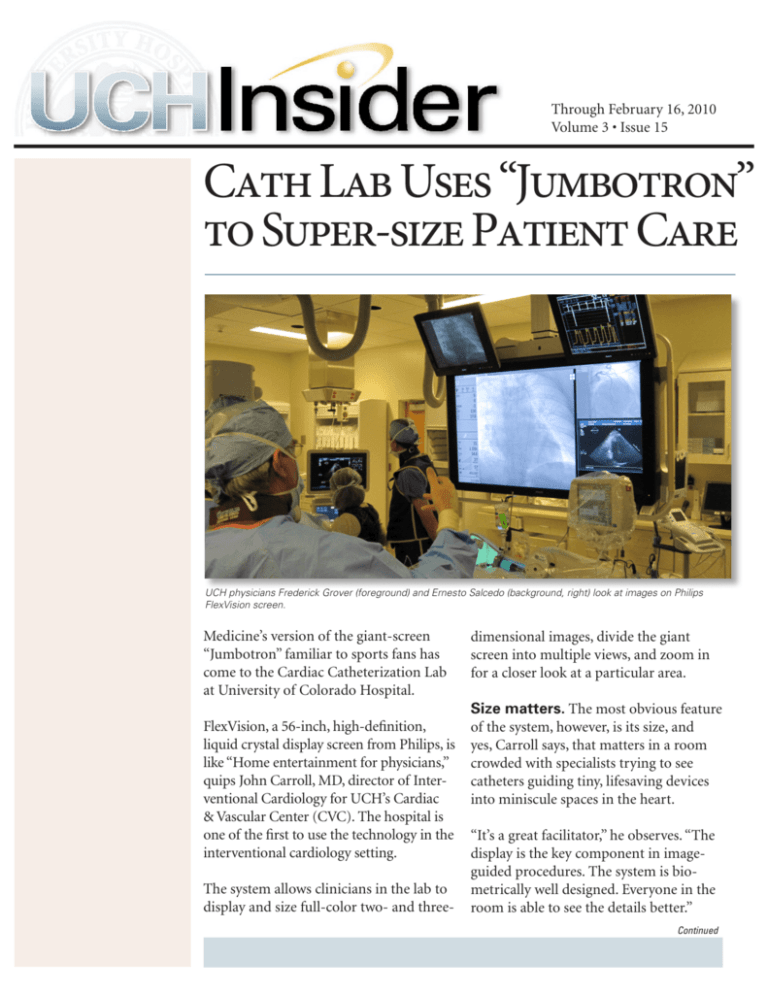

Through February 16, 2010 Volume 3 • Issue 15 Cath Lab Uses “Jumbotron” to Super-size Patient Care UCH physicians Frederick Grover (foreground) and Ernesto Salcedo (background, right) look at images on Philips FlexVision screen. Medicine’s version of the giant-screen “Jumbotron” familiar to sports fans has come to the Cardiac Catheterization Lab at University of Colorado Hospital. FlexVision, a 56-inch, high-definition, liquid crystal display screen from Philips, is like “Home entertainment for physicians,” quips John Carroll, MD, director of Interventional Cardiology for UCH’s Cardiac & Vascular Center (CVC). The hospital is one of the first to use the technology in the interventional cardiology setting. The system allows clinicians in the lab to display and size full-color two- and three- dimensional images, divide the giant screen into multiple views, and zoom in for a closer look at a particular area. Size matters. The most obvious feature of the system, however, is its size, and yes, Carroll says, that matters in a room crowded with specialists trying to see catheters guiding tiny, lifesaving devices into miniscule spaces in the heart. “It’s a great facilitator,” he observes. “The display is the key component in imageguided procedures. The system is biometrically well designed. Everyone in the room is able to see the details better.” Continued Through February 16, 2010 Volume 3 • Issue 15 • Page 2 The improved imaging paid off during a recent procedure in the Cath Lab. Carroll was part of a team operating on a patient admitted for repair of an atrial septal defect, or opening between the two upper chambers of the heart. Three-dimensional image of patient heart. Center of screen shows catheter carrying device to be inflated to plug hole in septum. Carroll and his colleagues looked at three-dimensional, real-time images of the heart, produced by an ultrasound test called a transesophageal echocardiogram that was performed by Ernesto Salcedo, MD, director of the Echocardiography Laboratory at UCH. An ultrasound transducer, inserted through the esophagus, produces images of the heart that are not blocked by the ribs and lungs. “We would have missed it.” After the first attempt to repair the hole, the clinicians gazed critically at the large screen before deciding there was still too much blood leaking from the left atrium back to the right. “It was a big, complex defect, a tunnel of rigid tissue,” Carroll explains. “The device did not conform well to it.” Echocardiogram shows device (top center of field) to repair atrial septal defect (ASD). So they removed it and tried again, this time with much better results from a different closure device. Then they realized they had more work to do. “From the outside,” Carroll says, “we had seen just one atrial septal defect. But as we were checking the results of our repair, we saw that something else was wrong, far away, at the other end of the septum, where it was hard to image.” Device (top center of field) being deployed to repair ASD. They discovered the patient in fact also had a fenestrated septum: five smaller holes clustered together. Continued Through February 16, 2010 Volume 3 • Issue 15 • Page 3 The team then placed a device in the middle of and overlapping the “five little windows,” which ranged in size from 2 to 6 millimeters, Carroll relates. “We’re optimistic we have blocked the majority of the abnormal blood flow in the upper chamber,” he adds. “We discovered we hadn’t gotten it all” with the first try, Carroll says. Without the improved imaging, he adds, “We would have missed it…We were able to navigate live, using 3-D images. That made it easier and more straightforward.” While he gives full credit to the technology, the procedures “require a huge team effort.” For example, he notes, Salcedo produces the ultrasound images while Carroll and others perform the procedure. “Dr. Salcedo is the eyes of the operation,” Carroll says. Cath Lab Ponders More Uses for Big-Screen Technology The Philips FlexVision system has already proven its worth in the Cath Lab, but John Carroll believes he and his colleagues have only scratched the surface of what it can do to revolutionize patient care. “Right now we are able to display different images that are big enough for everyone to see,” he says. “But in the future we may be able to display other information in different quadrants of the screen that will refresh our memory on things like the proper sizing of devices [used to make repairs in the heart]. We can use it as an extension of our cerebral cortex.” Carroll envisions hooking up a Mac or PC to the big screen to display “information on the fly.” For example, he says, the screen might display complications of a particular procedure in a checklist. “We could methodically go through the protocols for a rare situation, when the information is not fluid in our minds.” The strategies for marrying information and display technology are limited only by the imagination, Carroll believes. “It’s part of the future of making procedure rooms more efficient and better organized,” he says. “We love to have these kinds of opportunities to use our imaginations to improve patient care.” Subscribe: The Insider is delivered free via email every other Wednesday. To subscribe: uch-publications@uch.edu Comment: We want your input, feedback, notices of stories we’ve missed. To comment: uch-insiderfeedback@uch.edu