THE EFFECT OF JUMBOTRON ADVERTISING ON THE

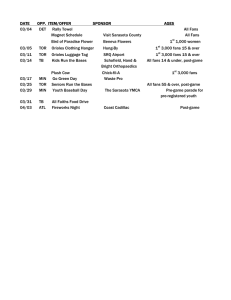

advertisement