advertisement

Contents

4

Interview

By ELlZABETI-I JACKSON

Independentfilmmaker Barbara McCullough hears the music ofspirits past and brings it into the

present in herfilms.

8

Displaced Desires

By STEPHEN BEST

In Young Soul Rebels director IsaacJulien winds a suspensefUl drama ofsexuality and interracial

desire.

CRITICS FORUM:

14

The Culture ofChauvinism

erheide

anella II

ia iawara

'a . Marshall

. eid

osen

Taylor

By l<ALAMu YA SAlAAM

Blackfilmmakers may have negotiated a detente with Hollywood, but what have they compromised?

18

The Positive Void

By CLYDE TAYLOR

The newjack critics are working their own politically correct agenda.

d ertising Director

i1a Reid

Fa ding Editor

a id icholson

85-1989

Blae Film Review (ISSN 0887-5723) is published four

i es a year by Sojourner Productions, Inc., a nonpo' corporation organized and incorporated in the

Oi trict of Columbia. It is co-produced with the Black

Film Institute of the University of the District of

Co umbia. Subscriptions are $12 per year for

individuals, $24 per year for institutions. Add $10 per

year for overseas subscriptions. Subscription requests

and correspondence should be sent to PO Box 18665,

Washington, DC 20036. Send all other correspondence

and submissions to the above address; submissions

must include a stamped, self-addressed envelope. No

part of this'publication may be reproduced without

written consent of the publisher. Logo and contents

copyright (c) Sojourner Productions, Inc., and in the

name of individual contributors.

Black Film Review welcomes submissions from

writers, but we prefer that you first query with a letter.

All solicited manuscripts must be accompanied by a

stamped, self-addressed envelope. We are not

responsible for unsolicited manuscripts. Black Film

Review has signed a code of practices with the

National Writers Union, 13 Astor Place,

7th Floor, New York, NY 10003.

This issue of Black Film Review was produced with the

assistance of grants from the Academy of Motion

Picture Arts and Sciences Foundation, the D.C.

Commiss'on on the Arts and Humanities, the National

Endo ment for the Arts and the John D. and Catherine

T. ac hur Foundation.

24

Peer Pressure

By JACQUIE JONES

Award-winning cinematographer Ernest Dickerson takes the director's chair.

Features

2

Film Clips

RememberingAlex Haley, Filmmakers On Violence, and more.

11

Books

Diary ofa Young Soul Rebel

12

Reviews

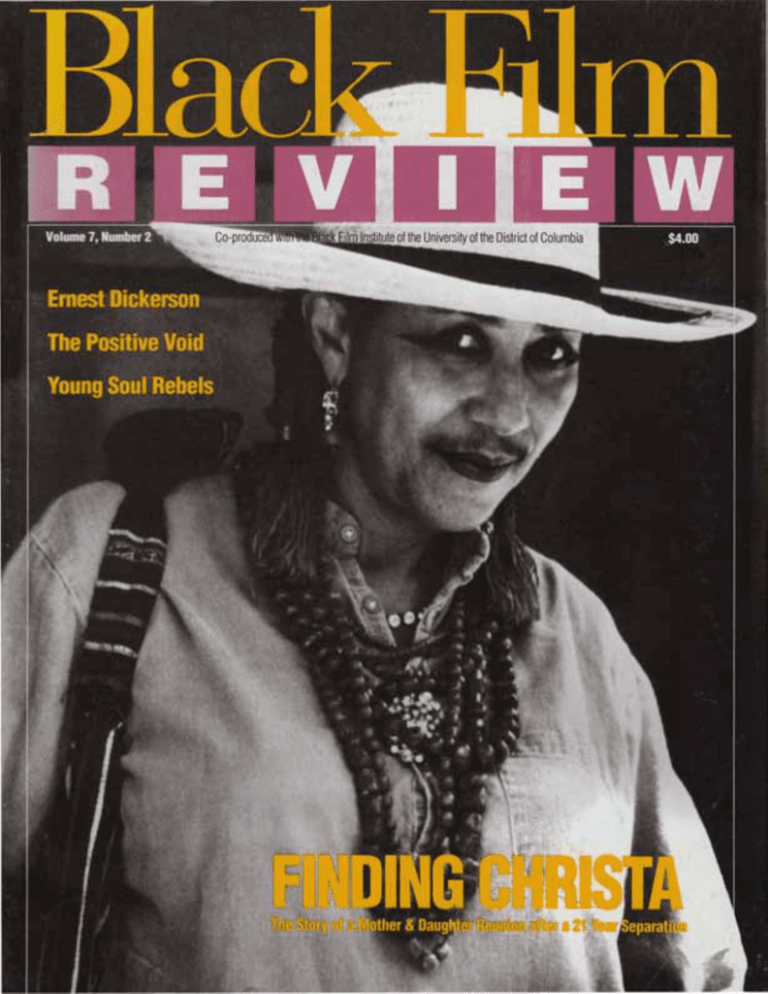

Finding Christa

FILM CLIPS

REMEMBERING ALEX

HALEY

"We'll never know where we're

going until we know where we

came from," Malcolm X once

told Alex Haley. Haley had not

written Roots yet-it was the '60s

and he was working with the

revered pan-Africanist on his first

book, The Autobiography of

Malcolm X But Haley, who was

fond of mentioning Malcolm,

understood the profound

significance of being intimate

with one's past history. He had

already begun the arduous twelve

years of researching and writing

that became Roots, an unprecedented chronicle of the African

American experience. Over the

years, he lectured on college

campuses, sharing his story like a

modern-day griot with gatherings

of Black students from Howard

University to Harvard. It was at

such a gathering that I first met

and heard Alex Haley. I say

"heard" because it was through

the power and humanity of his

voice that his imaginative

storytelling enveloped you.

On February 10, 1992,

shortly after midnight, Alex

Haley died unexpectedly from a

heart attack in Seattle, Washington, where he was scheduled to

speak. He was 70 years old.

He was born in Ithaca, New

York, but grew up in the rural

2

town of Henning, Tennessee.

After 20 years of military service

in the Coast Guard, he began

writing for magazines. He did a

series of probing one-on-one

interviews with celebrities for

Playboy and helped to popularize

this journalistic genre. It seems

appropriate that one of his last

efforts was hosting "Dialogue

with Black Filmmakers," a series

When the novel was adapted

into a 6-part ABC miniseries,

"Roots" immediately became the

defining television event of the

'70s and gave America a lasting

emotional experience about

African American history. It was

the highest-rated miniseries of its

time, and it revolutionized

primetime television storytelling

with its novelization of an epic

of interviews for Black Entertainment Television.

story.

The huge ratings success of

Haley was always quick to

point out that he was inspired to

"Roots" in 1977 was a surprise to

television executives. The

~ecome

a writer by the

storytelling of his maternal

conventional wisdom that whites

would not be interested in the

grandmother. As a young boy he

epic story of an Aftican American

listened as she traced his

compelling family history

through generations, all the way

back to a man she called "the

African."

was proven wrong. LeVar

Burton, who played the young

Kunta Kinte, observed that

"Roots" served to "galvanize the

As he began his writing

career, these stories stayed with

him, and he began to search for

documentation that would

authenticate his family history.

His astonishing feat of genealogical detective work across three

continents resulted in the Pulitzer

Prize-winning Roots. Haley

became the first African American writer to trace his origins

back to his ancestral beginnings.

In doing so, he told the story of

30 million Americans ofAfrican

descent, made it possible for us to

share in his profound journey of

discovery, and won our admiration and respect.

country, finally bringing us to

terms on a national level with one

of the ugliest episodes in

American history, slavery."

Unfortunately, and Haley

admitted to feeling badly about

this, it did not open future doors

for Black actors and filmmakers

as much as expected.

The popularity of the TV

series led to a sequel, "Roots: The

Next Generation," that brought

the family's story up through the

turbulent 1960s. It concludes

with Haley coming of age as a

writer.

"Queen," a 6-hour

miniseries about Haley's paternal

grandmother, a half-black, halfBlack Film Review

white product of a plantation

affair who was forced to seek her

destiny in the post-Civi~ War

South, is currently in development at CBS. The miniseries is

expected to air sometime near the

end of this year.-Roy

Campanella, II

FILMMAKERS ON

VIOLENCE

Producers George Jackson and

Doug McHenry, filmmakers

Warrington Hudlin and Robert

Townsend, and Oscar-nominated director and screenwriter

John Singleton were among the

well-known African American

filmmakers who criticized the

media for sensationalizing violent

incidents at movie screenings at

the National Association of

Theater Owners (NATO)/

ShoWest convention in Las

Vegas in February. All agreed

that it was not the films which

caused the violence and discussed

what theater owners can do to

prevent these incidents.

McHenry made the point that "a

cauldron of racism" has created

the social conditions that give rise

to such conflicts.

"It is an issue of media

responsibility not to engage in a

pre-release (witch hunt' as to

whether or not there will be

violence," noted Jackson. The

incidents ofviolence happen

mostl during a picture s opening

weekend. After that .t is the

continued emp asis in the media

that turns 0 e· ident into a

FIu

a ded lrhe

the press

its

future.

e orts ignore

e problem

articular film,

Dickerson's Juice,

or violence, the

such

is the

e foundation

ent to ban or censor

t the session,

resIdent, William

for

suc

Fano .

ha-e

pa

0

ealed that exhibitors

put under pressure by

community leaders and

to pull some of the

it comes down to

thea e being unable to safely

pa

e movies because of

o e ce then the question is

r e ofwhether or not such

Ian

r

get made.

Hile Townsend attributed

the riolence to exploitative

marketing campaigns that

emphasize negative and violent

Black stereotypes, the other

filmmakers explained that these

. cidents would happen regardof the showing of the films.

Producers Jackson and McHenry

convinced the movie executives,

exhibitors and filmmakers

present to pledge their support

for a campaign of public service

announcements to run in

theaters, targeting the issue of

violence.

SINGLETON GETS

ACADEMY NOD

When the Oscar nominations

were announced this year, John

Singleton at 23, became the

youngest person and the first

tribute.

African American nominated

Best Director in the history of the

Academy Awards. In addition,

Winners of the 1992

International Black Independent

Film, Video & Screenplay

Singleton received a second

nomination for Best Original

Screenplay for his debut film

Boyz N the Hood The film,

which grossed over $57 million

at the box office and is now

available on videocassette, tells

the story of three teenage boys

coming of age in South Central

Los Angeles.

"This is something that had

never happened before," said

Singleton. "It sure made the

white boys mad."-George Hill

WOMEN IN THE

SPOTLIGHT

(Saundra Sharp) for Best Short

Screenplay.

CAMPANELLA,

LANUEVILLE WIN DGA

AWARDS

Roy Campanella won the

Directors Guild ofAmerica

(DGA) award for his PBS/

ceremony in Beverly Hills in

tapes by and about women, is

now distributing the awardwinning hour-long videotape

Slaying the Dragon, produced and

directed by San Francisco

videomaker Deborah Gee.

and contributions of Black

women in film and television.

dramatic day category. Originally

broadcast on PBS, "Brother

The theme, "Black Women in

Film and Television: Portraits

and Portrayals," focused

attention on these contributions

and the creative talent that still

needs to be tapped.

The 1992 Hall of Fame

Inductees were actresses Rosalind

Cash ("Sister, Sister"), Helen

Future" has also been honored by

Clarence Muse Youth Award and

the late Dorothy Dandridge was

honored with a retrospective

Black Film Review

SLAYING ASIAN

STEREOlYPES

Women Make Movies, the

March. Campanella becomes the

first African American filmmaker

to win the DGA award for a

Journal" and "Sesame Street").

Actress Tempestt Bledsoe ("The

Cosby Show") received the

well-known edifice was previously MGM's Irving Thalberg

Building, named for the famed

head of production during the

studio's "golden years" in the

1930s.

Wonderworks television movie

"Brother Future" at an awards

The Black Filmmakers Hall of

Fame's 19th Annual Oscar

Micheaux Awards Ceremony,

held in February in Oakland,

California, spotlighted the history

Martin ("227") and Madge

Sinclair ("TrapperJohn, M.D."),

actress and writer Denise

Nicholas ("Room 222"), and

producer, director and editor

Madeline Anderson ("Black

by the American Film Institute

with its highly prestigious

Lifetime Achievement Award. An

edited version of the event was

Competition include Daughters of broadcast on NBC as a television

the Dust 0ulie Dash & Arthur

special in April.

]afa) for Best Film, Kokoyah:

In another tribute, Sony

Beast ofthe North (Malcolm

Pictures, where Poitier is based,

Johnson) for Best Feature

has named its main administraScreenplay and Dearly Beloved

tion building after him. This

feature film and the first in the

nonprofit distributor of films and

Slaying the Dragon is a comprehensive look at media stereotypes

ofAsian and Asian American

the National Black Programming

Consortium and the Colurnbus

women since the silent era.

International Film and Video

Festival.

From the racist use ofwhite

actors to portray Asians in early

Hollywood films, to Suzie Wong

Eric Lanueville won for an

episode of "I'll Fly Away."

Lanueville previously won for a

one-hour episode of "L.A. Law"

in 1989. Among other African

American directors who have

and 1950s geisha girls, to the

Asian American anchorwomen of

today, the videotape shows

through film clips and interviews

how stereotypes of exoticism and

won are Thomas Carter, who

docility have affected the

received the award in 1984 for a

one-hour episode of "Hill Street

Blues."

perception ofAsian American

women and the effects of these

images on their lives. As the

ALMNG LEGEND

Sidney Poitier, the legendary

screen star, was recently honored

recent protests against The Year of

the Dragon and Miss Saigon show,

Asian Americans are organizing

to challenge enduring stereotypes

and to fight for the opportunity

to represent themselves.

3

By Elizabeth Jackson

Filmmaker Barbara McCullough

nitially interested in dance,

Barbara McCullough

decided instead to pursue a

career in the visual arts, and

began to experiment with

photography, video and film.

McCullough first produced Shopping

Bag Spirits and Freeway Fetishes: Reflections

on Ritual Space (1980), a 60-minute experimental documentary that investigated the use of ritual in artists' work and how

this ritual touched upon their collective, Mrican pasts. A

second film that year, Fragments, reexamined the theme.

In 1981, McCullough produced Water Ritual #1: An

Urban Rite ofPurification, a poetic film that explored the use

of ritual for exorcising the societal frustration that engulfs

4

Black folk. In this ftIm, ritual is used to evoke the spirit-the

tool used to initiate change.

Also produced in 1981 was McCullough's short, The World

Saxophone Quartet This film provided a glance at the innovative jazz group in concert and conversation. McCullough's

most recent work, Horace Tapscott: Music Griot(1992), is an

hour-long examination of the man and the mind of this

brilliant keyboardist.

McCullough has served as the production coordinator,

national productions, for KCET-TV in Los Angeles, and is

currendy production manager for Pacific Data Images, a

company that creates computer animated imagery for motion

pictures and television. A graduate of the University of California at Los Angeles School of Film, Barbara McCullough spoke

with Elizabeth Jackson for Black Film Review.

Black Film Review

Black Film Review: You are near completion 0 yo r fourt in ependent piece

Hora,ce a seo t: Music Grot-a film 10

years in the

· g. Why this title, and

why this 5 ject?

Barbara cCullough: I chose the title

because a griot IS a storyteller in the

African tradition It is unto him that the

people look for the remembering. In this

film Horace not only remembers

through music but also the telling of the

oral . 0 of the musical life of the Los

Angeles community.

B • our ather was a musician. Did this

have an ing to do with your focusing

u n ·s material?

cCullough: I have always been

mesmerized by anyone who had the

po,ver to play music because it was an

art form I grew up around. I've been

m tified by the art process that allows

master musical artists to hear what they

hear, £Iter it through their bodies, and

transform it into something lyrical,

rhythmic, tender. This is why I selected

Horace Tapscott as my subject.

• It sounds as if musicians are almost

erect to you.

IcCullough: I've always considered

em the culture bearers, the "masterful

ones" who carry the force of life, the

songs of the ancestors, and the voices of

our gods from one generation to

another.

FR: The idea of "music griot" seems to

• corporate a sense of responsibility tothe Black community.

McCullough: My curiosity about the

artistic process has extended to how

artists fulfill their obligation, not only to

their art but to their community.

Horace is into community-sharing:

teaching, learning, exposing. And in the

10 years that I have been making this

fum, his commitment has grown

exponentially.

8FR: How did you evolve as a filmmaker?

McCullough: When I looked around, I

didn't see a reflection of my own interior

complexity. No reflection of me as a

mother, a creative person, an emerging

artist. The other women I kn~ didn't

see themselves either.

When I became interested in photography, video, then film, it was out of an

interest to make something from what

already existed, images from the community where I lived.

BFR: So your initial impetus arose from a

deep-seated need?

McCullough: Yes, exactly. A need to

relieve myself by making our image

accessible to others. A need to show the

endless lifestyles and expressions which

are part of the fiber of Black life.

BFR: Did you know'any Black women

- filmmakers when you started?

McCullough: No, but I knew a few

Black women artists, and I looked at

them in wonderment because they had

fo"und a way to express themselves. They

had educated themselves and, through

hard work, garnered the facility to

express themselves in a creative medium.

I knew about Bettye Saar and the

cultural base- of her imagery, assemblages

and collages bejewelled in the icons of

her heritage. I knew of her altars and

tabernacles that evoked the spirits, gods

and ancestors of an Mrican past.

BFR: When you decided to enroll in UCLA

film school during the '70s-the magical

decade that produced Charles Bumett,

Larry Clark, Billy Woodbury, Ben Caldwell,

Haile Gerima-you and Julie Dash found

yourselves struggling together.

McCullough: Julie was the first Black

female filmmaker I had known. I met

her the summer before school started

when she was attending AFI [the

American Film Institute] and editing her

film Four Women in the garage of a

mutual friend. A fire in the house where

she was rooming destroyed most of her

personal belongings-but Julie still

worked! This was the first time I had

ever seen a Black female image in film

that reflected my community. And what

knocked me out was that her character

was dancing to the music of Nina

Simone.

Later, Julie started and completed

Diary ofan Aftican Nun her first quarter

at UClA. She was bright, unassuming,

loved the Mrican "affects"-braids,

color, makeup. She was serious; she

knew from the beginning that she

wanted to make film. My other female

classmates included Sharon Alile Larkin.

In fact, my son Cephren played the

pesky little boy in her film A Different

Image. I also went to school with Carrol

Parrot Blue and o. Funmilayo

Makarah-who are still very active in

this community of Black women

filmmakers.

BFR: On Sharon Alile Larkin's film, A

Different Imag~ you hold credit as a

sound assistant. In fact, many of the

people you mentioned are crew for each

other's films. UCLA seems to have cemented your connections and fostered

your sense of support for one anothereven 20 years later.

McCullough: At UClA it was unwritten philosophy that you weren't just a

student but an independent filmmaker

existing in a -community of independent

filmmakers who supported each other's'

work as best they could. Most of the

time, no one had any real financial

support, and it took some of us years to

complete our projects. But the film

school was our factory and production

facility. Each one of us was a mini film

company' producing our very special

works. We basically learned from each

other and struggled through a system

that wasn't particularly nurturing. I

don't think that the faculty really

thought that there was a life for our

work beyond film school.

BFR: Did the feminist agenda surface

during this time?

McCullough: Yes, and that is why the

women of color ultimately joined

together-to form a sort of collective to

support each other's creative endeavors.

We knew we were dealing with sexism

and racism.

BFR: Your work, like Julie's and Sharon's,

Black Film Review

5

eals eavily· Africanisms, ritual. Your

ea fil, Shopping Bag Spirits and

eeway Fet·shes: Reflections on Ritual

Space, • corporates all of these things.

were the origins of this work?

cCullough: I knew a woman named

Senga engudi who did sculpture using

nylon stockings. She said it related to the

elasticity of the human body from

tender tight beginnings to sagging ends.

I decided to document her work and

found myself under the freeways of Los

Angeles as she wrapped freeway pillars

with juju bags of stockings, sand and

straw. She wrote the names of our

children on these fetishes as they swayed

25 feet high around those support

pillars.

BFR:Why?

McCullough: She wanted to infuse

magical energy into a purely utilitarian

environment. The quiet simplicity and

profound starkness of her work touched,

amazed and motivated me because of its

unique sense of the Mricanisms and the

femaleness. Though her textures were

coarse, the core of her work was soft and

full of love.

BFR: It sounds similar to what South

African songstress Miriam Makeba says her

mother, as priestess and healer of her

village, went through.

McCullough: Yes, what may have

seemed like odd behavior was, for me, a

step backwards in time to the movements and motions of some ancient

Mrican ceremony that I had never

witnessed before in my present life but

had felt and experienced in the past.

BFR: All of this became Water Ritual? A

spiritual excoriation, protection and

transformation borne out of a kind of

collective African consciousness?

McCullough: Exactly. All my life has

been spent collecting information, sense

impressions, visual and auditory signals,

spiritual cues that tell me that within

this culture of ours is something that we

cannot afford to lose. We must remember, and we must pass it on.

6

McCullough: True. I recently heard the

broadcast of a speech by the late James

Baldwin which was made when he was a

university professor. Baldwin obviously

enjoyed his students but could not

reconcile the fact that so much ofwhat

he understood from his life and times

was so foreign to them.

BFR: Was this just the difference between

one generation and another?

McCullough: That, and a lapse of

information and, ultimately, perspective

due to the fact that what is disseminated

every day doesn't tell us much about our

Black lives, much less Black heroes.

• Your brilliant determination and that

o your female colleagues has allowed you

o preva·l-but Id's be real. This fight for

some semi-accurate representation of who

"wen are s been a bitch, right? And film

continued on page 30

D YES, I want an AAFS T-Shirt!

Enclosed is $12 for each shirt

(all white on black, size XL)

BFR: Your Water Ritual #1: An Urban Rite of

Purification continued this exploration

into the application of Africanisms onto

"modernity."

McCullough: A friend of mine had a

nervous breakdown. Her friends decided

to care for her at home, were watching

her around the clock, and asked that I

come over and lend support. On the one

hand, I was shocked and confused by

what I saw, but, on the other, there was

something very familiar. My friend was

naked in a bare room. She talked to

herself in rhymes and drew cir~les on the

floor. She stood and danced as if she

were part of an ancient ceremony. She

looked as if she were in the process of

exorcising herself of some energy she

couldn't control. Everything she did was

highly ritualized. She engaged in

unconscious symbolic action by creating

a circle around herselfwithin which she

withdrew for protection.. She made

BFR: It sometimes seems as if our collective memories are becoming more dim.

gestures like a priestess signaling a

protective spirit. She spoke in tongues.

.ATLANTA

AFRICAN

FILM

SOCIETY

,------

D YES, I want to be on AAfS

Mailing List $5 annually.

$12X _ _ T-Shirts= _ _

Mailing List = $5Total =

Name

_

Address

City

_

State

Zip

Make your check payable to the At!anta African Film Society

POST OFFICE BOX 50319 • ATLANTA, GA 30302

Black Film Review

_

SC

IC EAUX KATHLEEN

CO I S SPIKE LEE EUZHAN

CY S C AIR BOURNE BILL

E ELIKSHABAZZ ELLEN

ER MICHELLE PARKERSON

E RY HAMPTON MED HONDO

SOULEMAYNE CISSE YOUSSEF

HINE HAILE GERIMA SAUNSHARP ROY CAMPANELLA,

EGINALD HUDLIN CHARLES

URNETT MEDHICHAREF AVERY

ROOKS

AYOKA CHENZIRA

STANLEY NELSON SIDNEY POIROBERT

ER ISAAC JULIEN

OOKS IDRISSA OUEDRAOGA

SARA MALDROR

BILL DUKE

JEAN-MARIE TENO ARTHUR SI

BITA KATHY SANDLER NEEMA

BARNETTE BILL FOSTER TOPPER CAREW ROBERTTOWNSEND

MAUREEN BLACKWOOD JOHN

AKOMFRAH

MARTINA ATILLE

ROBERT GARDNER

DEBRA

ROBINSON

MURIEL JACKSON

WOODY KING

MELVIN VAN

PEEBLES DUANE JONES GASTON KABORE

JULIE DASH

BROCK PETERS DIDI PETERS

YULE CAISE DONNA MUNGEN

RONALD WAYNE BOONE MARLON RIGGS

BEN CALDWELL

ZEINABU IRENE DAVIS MICHEL

KHLEFI

OUSMANE SEMBENE

JAMES BOND III ELSIE HASS WILLIAM GREAVES •

AND MORE

Black Film Review

Blacl~

E.. . .-. . . -.

IiIOl!JDOrn

the vision.

the voice.

From L.A. to London and Martinique to Mali.

We bring you the world of Black film.

Black FIlm Review brings you news, reviews

and in-depth interviews from the most vibrant

movement in contemporary film. Published quarterly and recognized internationally, Black Film

Review is the foremost chronicle of the efforts of

filmmakers throughout the African diaspora. And

with Hollywood commentary as well as features on

other filmmakers working outside the mainstream

industry, there is always something for everyone.

Subscribe today, or send $3 for a trial issue.

You won't want to miss another one.

, , Black Film Review takes up where the

likes of Variety and Premiere leave off

because it gives me in-depth articles and

interviews about film that's happening in

the other three quarters of the worldthe majority of the world. And as a new

producer, it's heartening to see acelebration offilm that reflects my efforts andmy

perspectives. , ,

Gloria Naylor, Author and Independent

Producer of Mama Day.

~----------------I

DYES!

Please start my subscription

with your next issue enclosed is $12.

DYES! Please send me a trial copy

enclosed is $3.

Name - - - - - - - - - , - - - - Address - - - - - - - - - - City - - - State - - - Zip - - Clip and send this coupon with payment to

Black Film Review, PO Box 18665

Washington, DC 20036

L

~

7

Perhaps more than afilm director, Isaac

Julien can be viewed as avideo jockey of

contemporary Black British cinema.

Consistently and complexly, films such as

Territories (1985), Looking for Langston

(1989) and, now, Young Soul Rebels use

music to enact adynamic tension between

pleasure and identity.

By Stephen Best

n Territories, Julien

past and to show how

used the American

this relationship is infolk music of Joan

flected by questions of

Baez and reggae

identity and sexuality. In

music (the sound-sysYoung Soul Rebels, his

tem and dance-hall type)

latest film, Julien uses

American soul and funk

to thematize the hybridity

of the annual celebration

music as a means of

of the London Carnival.

arriving at an opposiMo Sesay and Valentine Nonyela in ascene from Young Soul Rebels.

He used the blues and

tional, political space in

house music in Looking

which to image the

for Langston to articulate an understanding of

contradictory, liberatory nature of Black gay

the role of the present in the construction of the

desire.

Opposite, director Isaac Julien.

8

Black Film Review

Ostensibly a murder mystery, Young

Soul Rebels begins with the killing ofTJ,

a Black gay man. As the narrative

unfolds, it reveals for us the effects of

this killing on TJ's friends-Chris, who

is straight, and Caz, who is gay. Around

the suspenseful drama are wound

numerous subplots of interracial desire.

Ultimately, the role ofsexuality in the

conflict between cultural forms and the

multiple dimensions of Black masculinity become as important as the killing.

Consider the other major

element of the film's beginning: the Parliament cut "PFunk Wants To Get Funked"

places the audience ,through

sound, to use the words of the

tune itsel£ in "the home of

the extraterrestrial brothers,"

an-other (alien) space beyond

punk's anarchic rejection of

Britishness and reggae's

nationalism. This new space

Julien creates is not constrained by antagonisms of

musical forms like punk,

whose followers were raceblind until they hooked up

with reggae-whose own

devotees were, for the most

part, blind to the issue of

different sexualities. In fact,

Julien frequently uses music

in this film to provide the

viewer not only with a kind of

historical perspective, but also

to highlight these musical

forms as elements in conflict.

like and, in fact, be collusive with state

strategies of policing.

Consider the context and nature of

the murder in Young Soul Rebels and the

acts of surveillance it triggers: In the

film's opening scene, we see TJ emerge

from a dark and dense thicket of trees. It

is late at night. TJ carries a boombox

and fiddles with it until he finds the

Soul Patrol pirate radio broadcast. The

camera tracks him as he walks in front of

a gathering ofwhite men who are in the

Several scenes later, following TJ's

murder, Caz passes this same site during

the day. The police, who have roped off

the tree where the murder occurred, spot

Caz and fIX upon him, for the moment,

as a potential suspect. In the next scene,

Chris passes this same spot and he, like

Caz, is spotted by the police and

cCpoliced" for the duration of the scene.

The murder scene and the subsequent park scenes establish a relationship

between Black desire and the terror of

whiteness. Julien works to

unravel the fIXity of that

terror in the Black imagination by creating a space for

Black male desire ofwhite

male bodies and, further, for

a more sexually and racially

ambivalent desire for Black

men's bodies. This is not to

deny the extent to which the

slippages between policing

and cruising are deeply

meaningful to Julien.

As with most of the other

recent films that deal with

Black gay subculture, Young

Soul Rebels cannot dissociate

surveillance from the question of desire. These elements

can be found in Julien's

Lookingfor Langston in its

representation ofccthe Club,"

a private and safe space for

pleasuring, free ofccthugs and

police." Marlon Riggs'

Tongues Untied suggests this

relationship, as well, in the

film's interrogation of the gay

The paradox is that, in Young Sophie Okonedo and Valentine Nonyela in ascene from Young Soul Rebels.

white male gaze as a structurSoul Rebels, "psychic" migraing element of particular

tion to this domain of conflict

park to get down to the business of

networks of desire in arenas such as The

is often accomplished through spatial

Castro. Less critical and self-reflective

cruising. When TJ stops to lean against

displacement.

a tree, he is approached by a white man,

Unfortunately, the "hustle and

analyses emerge in a film like Jennie

bustle" of displacement can serve as a

who we suspect has been watching TJ

Livingston's Paris Is Burning, which

strategy for social control. In colonial

for the duration of the scene; he asks,

steers clear of interrogating its own

and racial politics, this tactic is called

"Wot's your name?" TJ responds,

privileging of the ethnographic gaze.

"Name? You a policeman or what?" The

divide-and-conquer, though I refer, in

Young Soul Rebe/1 representation of a

elision between cruising and policing is

this case, to the way in which gay

white male project of surveillancepractices of cruising can be made to look revealed in all its nakedness.

cruising and policing-that occurs in

10

Black Film Review

the same space and works on the same

bodies is of a piece with a recent debate

on the desire for Black men's bodies and

the desire of Black gay men that centered around the photographer Robert

Mapplethorpe, particularly around his

works Black Males (1982) and Black

Book (1986). On a certain level, Julien's

and Mapplethorpe s arks suggest

similar things about the ays in which

Black men s bodies circulate in particular political, social cultural and erotic

spaces. Young Soul Rebels represents a

kind of third-stage deconstruction of a

currently popular analysis of the Black

male body in Mapplethorpe's oeuvre.

T a date, the debate has taken two forms.

In one, Mapplethorpe has been read

as the archetypical proponent of "the

look, ' the white male gaze of mastery

that locks the nude studies of Black men

in a racial hierarchy that is historically

collusive with the power and privilege of

hite masculinity. Under this optic, the

Black male nude serves as the necessarily

contradictory sign of a set ofwhite male

fears and fantasies-"the hypersexed

buck" and its orgiastic/fantasmatic

inverse reflection, "the Black daddy." In

other words, Black images satisfY white

pleasure.

In another, the tendency has been to

read the images as the sites of competing, envious desires. Images of Black

men, as they are consumed by Black

men, trigger feelings of ambivalence

precisely because of the presence of a

competing level of consumption by

white men for the same images. This

position, like the first, gets snagged on

the question of the objectification of the

Black male body and its attendant

anxieties.

In his films, Julien attempts to move

beyond objectification towards more

murky and difficult questions of love

and the intersecting passions that

circulate between Black men and white.

At the level of narrative, Julien places

continued on page 23

By Pat Aufderheide

Diary ofa Young Soul Rebel

By Isaac Julien and Colin MacCabe

London, England: British Film

Institute/Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana

University Press, 1991, paperback, 217

pp., $18.95 [$45 cloth].

Isaac Julien is aBriton with roots in the Caribbean whose film worksTerritories (1984), The Passion ofRemembrance (with Maureen Blackwood,

1986), This Is Not an AIDS Advertisement(1988), Looking for Langston

(1989)-have both captured and shaped aconsciousness. He works in the

internationally respected Sankofa FilmNideo Collective with other Britons of

color; the workshop was created by the and-riow-for-something-completelydifferent TV Channel 4.

Colin MacCabe is awell-known British film theorist-turned-administrator.

As producer of challenging work in the British Film Institute Production

Board-work showcased at Channel 4-he has found away for theory to meet

practice.

The two of them worked together, as director and producer, respectively, of

Young Soul Rebels, athriller that not only reincarnates amoment in recent

English racial history but also boldly addresses long-muffled, enduring

conflicts of gender, sexuality and desire.

continued on page 29

Black Film Review

11

FINDING

CHRISTA

By Valerie Smith

MythsaboutBlack mothersabound

inAmerican culture. Black mothers

often loom large tIS figures ofselfsacrifice and boundless love in stories by Black women. In popular

accounts offamily life authored by

men-Moynihan, Moyers, and

Singleton, for example-Black

mothers are often blamed for the

emasculation of Black men and,

consequently, the perceived decline

in the quality ofBlack community

life·

12

Black Film Review

inding Christa, which explores

family's life in the late '50s. Interviews

with friends and relatives, however,

confirm Billops' account of the limited

options available to single mothers at the

time. In one striking moment, Billops

reflects upon the fact that although those

close to her did not want her to give up

the child, no one offered to keep Christa

or was able to help her in significant

conventional documentary techniques:

one mother's decision to give up

archival footage, interviews and still

her four- ear-old daughter for

photographs.. But here, the film moves

adoption and the reunion

into what the scholar Barbara Lekatsas

ben een the n 0 omen twenty-one

calls a "surreal theatrical interlude" in

years ater restores a much needed sense

which playwright George C. Wolfe,

of balance to representations of maternal

Billops and Christa perform. Wolfe plays

love "and po, er

the role of the emcee of a motherFinding Christa, a bold and brilliant

daughter recital for which Billops is

documentary written,

auditioning. Billops,

produced and directed by

dressed in a frilly, white

Camille Billops and James

dress with a blue sash,

Hatch, is Billops' own story.

waving a feather boa,

The Elm opens with a

attempts unsuccessfully to

photograph of the fourlip-synch to her own voice

year-old Christa as she

yodelling on the

soundtrack while a pianist,

appeared shortly before

seated behind her, accomBillops gave her up. The

panies her. Billops, clearly

adult Christa speaks in a

uncomfortable in this role,

plaintive voice that reveals

to associate meeting

seems

her sense of longing and

Christa with confronting

betrayal: "My last memory

her own failure.

of you is when you drove

off and left me at the

As Billops takes her bow

Children's Home Society. I

and turns to thank the

didn't understand why you

pianist, she discovers, to her

left me. I felt so alone. Why

horror, that the accompadid you leave me? It's been

nist is her daughter. The

so long since I felt comcamera then cuts back to

plete." The film struggles to

Billops. in her loft. It is in

this moment, in a voiceanswer Christa's question.

over, that Billops relates her

In the loft she shares

with Hatch in New York

decision to let Christa visit.

City, Billops plays a tape she

While the first section of

has received from Christa

the film focuses on Billops'

George ·C. Wolfe in ascene from Finding Christa.

after a separation of more

story, the second centers on

than twenty years. Billops

Christa-describing her life

ways.

after she was left at the Children's Home

explains her decision to a friend calmly

The reasons b.ehind Billops' choice are Society. Through interviews with

and directly: "I was trying to give her

Christa, her adoptive siblings and

as complex as the assortment ofvoices

something else, because I felt she needed

adoptive mother, Margaret Liebig, we

that contribute to the film. From the

a mother and a father. I'm· sorry about

that she found what appears to be a

learn

testimonies, we learn that Billops gave

the pain it caused Christa as a young.

Christa up because she did not think that· nurturing, loving family. Liebig, a singer,

child, but I'm not sorry about the act."

enco.uraged. Christa's love of music. This

she would be a good mother; she lacked

The film then takes viewers back to

sufficient family support; she wanted to

support and encouragement notwiththe community in Los Angeles, where

be free to develop her talents as a visual'

Billops and her family lived· and where

standing, Christa is· shown through

artist. One cousin, Bertha, believes that

she made her choice. Clips from home

pantomime and home video sequences

movies taken at Billops' baby shower and she gave up her child in order to be with

to be' unhappy with both her personal

still photographs of Christa being bathed Hatch,. who is white and 'whom she

and her professionall\fe. Liebig encourmarried years later. _ages.herto find her biological mother in

and playing under the Christmas.tree reUp to this point, the film relies upon

order to satisfy her longing.

create the apparent joys of this "perfect"

Black Fibn Review

13

year's Sundance Festival, is the third film

The film does not idealize the reby Billops and Hatch. Each of their films

union, which is played out in a number

focuses on the sort ofstory that middleofsettings. In a meditative moment,

class America commonly suppresses.

Christa describes Billops as a cactus who

doesn't want to be touched, while she

Suzanne Su:zanne (1982) investigated the

ees herself as an octopus who can't

history of drug abuse and domestic

violence in the family of Billops sister

ouch enough. And in another theatrical

interlude, in which mother and daughter Billie. Older Women and Love (1987),

inspired by the relationship between

share family photographs and accounts

as if they are playing cards,

viewers glimpse the rivalry

that exists between the two

women. Finding Christa

ends tentatively with

muted, dreamlike shots of

Billops and Hatch waving

sparklers and welcoming

Christa home.

The visual style of

Finding Christa complements its themes and

convictions. The intelWeaving of interviews and

archival footage presents

one set of facts, but viewers

suspect that truths too deep

for direct testimony reside

in the hallucinatory interludes. Moreover, the

striking contrast that the

film subtly draws between

Christa's two mothers

undercuts any monolithic

notion of Black motherhood. Indeed, the very

Vantile Whitfield in ascene from Finding Christa.

primacy ofbiological

motherhood is challenged.

The interactions between Christa and

Billops' octogenarian Aunt Phine and a

younger man, explored the erotic lives of

her two mothers remind us that the

older women. All three works challenge

mother-daughter relationship is at least

the myths about women's sexuality and

partly constructed and maintained

ideologies offamily upon which middlethrough continuous renegotiations. By

class life in the United States seems so

exploring the circumstances that surrounded Billops' choice, as well as the

fully to depend.

Finding Christa might be viewed as a

complex issues that emerged from the

reunion, the film dismantles idealized

companion film to Su:zanne Su:zanne.

conceptions of motherhood that often

Billops and Hatch intended their first

deny the complexity of Black women's

film to address Billops' niece Suzanne's

lives.

recovery from drug addiction. But

Finding Christa, which shared the top

during the course of their interviews,

Billie and Suzanne were forced to

prize in the documentary category at this

14

Black Film Review

confront the intensity of the violence each

had sustained at the hands of her husband

and her father, respectively. The film thus

situates the account of drug abuse within a

narrative of family violence, prompting

mother and daughter to recognize the

uneasy silence upon which their mutual

oppression had depended.

Suzanne Su:zanne not only attempted to

dismantle the idealized

notion of the perfect family.

By both undercutting the

authority of documentary

evidence-family photographs and home moviesand revealing the artificiality

inherent in the process of

documentary filmmaking, it

also challenged viewers to

question how they arrive at

the truth.

The account of Billops'

relationship with Christa

lurked on the periphery of

Su:zanne Suzanne. Christa

appears, in that film, as an

infant and toddler in photographs and clips from Bell

and Howell home movies;

Billops and Christa sang the

title song together. In

Finding Christa, the filmmakers bridge the gap between

the wistful image captured

on screen and the haunting

voice heard at the beginning

and end of Su:zanne Su:zanne.

By addressing the subject of domestic

violence, Su:zanne Su:zanne took on a topic

that has only recently become speakable in

representations of families, especially of

Mrican American families. Finding Christa

is even more daring, for, as Lekatsas has

written, "a mother who gives up her child

is considered even lower on the scale of

civilization than a brutal father."

Valerie Smith, associate professor ofEnglish at the

University ofCalifornia, Los Angeles, writes about race,

gender and culture.

Inding Christa's production Director James Hatch.

Black Film Review

15

E.CULTURE

CH U IHIS

PART II

By Kalamu ya Salaam

In the last issue tfBlack Film Review, Kalamu ya Salaam surveyedsome ofthe

recent Black Hollywoodfilms in his essay c,'Black Macho: The Myth -ofthe Positive

Imqge. "In that:article, the author detailed what he saw as the Jatalflaw" ofmany

oflastyearsfilms: ,cthestereotypingand denigration,ofBlack,wo.men and the

.projection ofeither capitalism or criminality t1S-accepta:ble, even laudatory, economic

pursuits."Here, wepresentpart two ofSalaams assessment tfour roles as African

American mediaproducers-and consumers.

he real deal is

that because

of our malesexual· insecurity and

an often unstated,

nonetheless allconsuming, desire to

expr~sourmanhood

through domination

of others, most of us men seldo'm, if

ever, address theissue of either'our own

personal sexualchauvin:ism or systemic

sexism, nor are· we, prepared to ~be :selfcritical about our indulgent efforts to

produce profitable; status~quoacceptable

"prot~t"art.

",Prot~t"

artists' invariably want their

work to be judged ~esameas "all other

woik"-andthat is the problem. Are

Black' movies' really the same -as _mainstream movies? Are we advocating the

same goals, are we using the same

language?

For some,'B-Iackness is :simply a .racial

16,

issue and has little to do with culture

and consciousness. For others, it.is

deeper than skin. Consider the ·same

question, but instead of focusing on

cinema, let's focus on music. Is our

music the same as mainstream music?

The jazz,gospel, blues, funk, rap

answers are obvious. The problem with

most commercial Black movies is that

they are hook~laden, top 40-oriented

hits that are contrived in the studios to

make a buck.

While some may perceive my criti.cism as exaggerated, even a cursory

review oflast year's-crop of Black movies

will show a general acceptance of the

economic system, often through"the

glorification of criminality or the simple

avoidance of any economic critique

'beyond "they:keep us·from getting

j·obs"-as if the goal was to get ajob

'rather than .to secure economic self,sufficiency. (A "job," after all, is all

'Clarence Thomas wanted, albeit a

Black Film Review

lifetime job.) And quiet as it's kept, most

ofthese new-Black movies are made by

men who are looking fo,r an -opportunity

to get their rums shownin the big

houses and-hoping also, one guesses, to

win the prestigious awards.

These movies eitherignore orcarnou:flagemoney.pressures, as:in Livin'Large,

where the "hero" keeps getting promoted while battling villainousprofessional white women and receiving

support and -partnership fromsympathetic white males. Clarence Thomas

notwithstanding, .that is -hardly -a realistic

.presentation of how the system gen,erally

works.

How is it that new Black movies

c()ntinue to avoid realistically dealing

with the main driving forces motivating

the actions and reactions of the vast

majority ofMrican American mal~?

Responding to my critique of a recent

movie, my teen-aged son replied, "Well,

.ifI wanted to see reality, I'd look out the

window. I go to the movies for entertainment." His view contains a common

assumption that, somehow, entertainment is value-free, or at least nonnegative. As we talked further, we agreed

more than we disagreed. One point of

convergence was on the absolute

necessity of box office support for these

efforts. Hollywood will offer no opportunity for serious, "critical" Black movies

unless there is a market for Black movies

in general. But the solution to our

problem lies not simply in bolstering the

existent commercial system.

What we really need is to expand and

strengthen the independent and alternative network that was sought and

worked toward in the early '70s by

independent Black filmmakers and is

continued now by the work of a handful

of sisters and a smaller number of

brothers.

The reality is that many, if not most,

young directors will choose to go the

Hollywood rather than the independent

fum route. The Hollywood system will

give one of two choices: either have the

fums ghettoized as low-budget movies

aimed exclusively at Black audiences, or

create films which have been designed,

some would say "bleached,"·to conform

to the aesthetics of the general market.

Nevertheless, these constraints and

considerations should not be used as a

rationale for the wholesale submission to

system stereotyping and adoption of

exploitative subject matter or modes of

presentations.

To make matters worse, there is no

Black-owned or even Black-controlled

infrastructure for distributing and

showing movies. Black directors face all

of this in their efforts to make fums.

Thus, while we tend to see the movie

itself as the sum total of the artistic

effort, we as viewers seldom confront or

take into consideration the plethora of

problems Black moviemakers facefrom raising capital and making contacts

to sell projects, to getting relevant

promotion and broad-based distribu-

tion.

New Black directors must also deal

with the fact that they are not in the

starting lineup and instead are pinch

hitters. Usually they make it to the plate

at best once a game, and when they do,

they had better get a hit if they hope for

another batting opportunity. All of these

issues impact the creative decisions that a

director must make. In many ways, the

pressures are unimaginable to the

average VIewer.

There can be no doubt that the

tempering of the Hollywood production

system, which includes the vicious

vicissitudes of the marketplace, functions as a form of censorship, even if no

more than to induce an internalized selfcensorship which manifests itselfby

directors second-guessing themselves

and meeting criteria that are completely

foreign to their films' subject matter.

This is essentially the problem that

confounded Michael Schultz, who is a

director with an admirable track record,

in his attempt to get Livin'Large

produced.

While I will not argue that only men

feel these pressures, I will argue that,

given the overwhelming prevalence of

men as the movers and shakers of the

industry, there is a male thing going on.

In other words, the prevalence of the

white male point ofview, in one way or

another, informs and colors the relatively few films which are made.

This set of conflicts is the seldom seen

underbelly of Black commercial fums.

So while, on the one hand, I am very

critical of most of the new Black films,

on the other hand, I understand that

these films represent at best a negotiated

detente between directors and a movie

industry which has its own mores and

methodologies, nearly all ofwhich are

diametrically opposed to the goals of our

directors-the one exception being the

insistence on macho.

This is where the collusion occurs.

Since raw racism is now outmoded, a

Black male can buy into the system

Black Film Review

based on acceptance of sexual chauvinism and reticence on economic issues.

This becomes the matrix out ofwhich

we get the "Clarence Thomases" of the

movie industry-men who deny their

complicity in a sexist system and refuse

to recognize any sexism in their own

behavior, and who, at the same time,

become apologists for-and sometimes

even advocates of-the dominant

economic system.

It is a romantic dream, at best, to

expect that individual directors, male or

female, can withstand the pressures of

this social system and, at the same time,

produce high-quality, relevant movies. It

is a tragic commentary on our predicament that those who in practice most

strongly espouse this idealistic illusion

are the same ones who are most vulner-·

able, those individual directors and

cinema artists.

The real solution to our problems

transcends aesthetic concerns and lies in

the creation and maintenance of

alternative and supportive social systems.

In this case, we need to construct

alternative distribution networks and

alternative film clubs, societies and

festivals. In the long run, what we're

really dealing with is not just a simple

critique of particular films, but rather a

critique of the function of fums within

the society at large, a critique of the

production of films, and a critique of

ourselves as both the producers and the

consumers of cultural productions.

In today's pop-culture marketplace,

entertainment means more than amusement. The fantasy-producing industry

of Hollywood is a reality that must be

dealt with. And whether they want to be

or not, new Black male directors, who

now represent the largest percentage of

people of color who get an opportunity

to make films, are on the front line of

this struggle. If they are to succeed, they

will need our critical support.

Kaldmu ya Salaam is a writer and music producer in

New Orleam.

17-

By Clyde Taylor

riticism of Black cinema has advanced in

quantity and quality in the last couple of

decades-promising in ~versity·to

.--'~.

/

lend form to a developing Black film culfure. But,

ironically; this slowly developing critical discourse faces

a setback with the coming ofthe latest wave ofBlack

/

movies from Hollywood. If critical intelligence takes a .

nosedive these days, it will follow a pattern set with

other Hollywood "booms" in Black cinema in the

early '70s and, before that, in the late '30s.

18

Black Film Review

A rush of Black-oriented movies from

Hollywood typically creates the specter

of a crisis of imagery. Great expectations

are raised in the blizzard of media

attention. And soon the Black population becomes fired up about the possibility that the Black screen image has

become a focal point for the discu~sion

of the issues and dilemmas facing Black

society. This is exactly the response one

would desire from a Black film culture,

were it not infested with commercialism,

celebrity glitz and media hype. With

these mendacious energies involved,

criticism sinks to its lowest levels. Large

stakes generate paranoia, and pop-think

becomes dominant. Rumors spread.

Conspiracies are suspected.

The pied piper of this retarded media

mentality is the doctrine of "positive

images." Where most of the directors of

the most recent Black independent fdm

movement-Haile Gerima, Julie Dash,

Spike Lee and pre-House Party

Warrington Hudlin--eonsistently tried

to educate their audiences about the

limitations ofpositive images, the n~est

directors in Hollywood-John Single-

ton, out of his youth, perhaps, and

Mario Van Peebles, out of his cynical

-ambition, perhaps-have raised the cry

of positive image to burnish the reputation of their films.

Rising to the bait and to the lure of

media fascination, a breed of "new jack

criticism" has appeared, spreading

confusion as if we had learned nothing

since the outcry over Superfly. Reviews

and essays bubble up and then sink back

into a massive pool offrustration,

resentment, envy and impatience-the

quandary where disempowerment

reproduces itself

There's nothing positive about

positive image critique in its new jack

phase. New jack critics may mention a

Scene from Boyz Nthe Hood.

Black Film Review

director or movie that meets their

approval, but only to get ammunition

against those-they hate. New jack critics

never spend time appreciating or

supporting what's right with movies

they like. They never phrase their

critiques in a way that would help the

ftlmmaker learn something. That would

betray the schoolyard mentality of

"positive" critique: Say

something appreciative,

and you might get

jumped for the shakiness ofyour negative

gaze. It reminds me of

the crows' song in The

~z: You can't win;

you can't get even; and

you can't even get out

of the game.

The feverish atmosphere of crisis that

nurtures new jack

positivism is too itchy

for clarifications,

distinctions, considerations of circumstance.

Principles of criticism

are dismissed as wimpy

distractions. It is

precondemned to

binary oppositions

useful only for totalitarian extractions of

confessions. It revels in

the kind of Manichean,

either/or, good/bad,

black/white zero-sum

thinking that resurgent

Black intellectuals have

targeted as one of the

most serious liabilities of

Occidental thought.

You find this "born

yesterday" refusal to see

that films are .made

from different predications: some to make

money and garner fame,

some to express an

artist's sensibility, and

19

Waymon Tinsdale III (Joseph C. Phillips, right), Natalie (Halle Berry) and Bobby Johnson (Tommy Davidson) in Strictly Business.

some to speak to social issues in a

reflective way. You find this heavy

armature leveled at cliches in moneyhustling movies coming from an

industry defined by its successful

marketing of cliches.

One disingenuous pose competes

with another. To pretend not to understand that the cultural imaginary of

almost every known society lies captive

of masculinism-and that it takes an

astonishingly brilliant effort to powerfully reconfigure those values, as do

Toni Morrison, Alice Walker and Julie

Dash-rivals the innocence of not

knowing that a gangster movie filled

20

with lots ofsex and violence is predicated on Hollywood codes rooted in an

ancient capitalist culture industry.

Wearing this new-born innocence on its

sleeve, new jack criticism conjures up a

rage as convincing as the oath of

directors like Mario Van Peebles to offer

positive social critiques, a media rage as

compelling as the liberation philosophy

of Michael Jackson's videos.

The snap-fingered judgment"Hated it!"-of the critics on the

television show "In Living Color" are as

reasonable as some of these critiques,

and more economical. The posture of

political correctness (PC) is so intense

Black Film Review

that you are not expected to ask which

positive image, according to whose

ideology, and building on what social

consensus ofwhat is right for everybody.

Positive images are confused with the

man in the mirror.

This clan of critics makes the same

gesture toward the makers of the new

movies as the white woman clutching

her purse when a Black man enters the

elevator. There is the same assumption

of guilty intentions, drawn with fine,

imagined precision. Black fums that fit

the text of the oncoming sermon are

lumped indiscriminately together and

essentialized as a conspiracy.

sucked back into this level of criticism

by the need to rebuke the positivity

claims of some of the new directors. His

essay, "Black Macho: The Myth of the

Positive Message" (Black Film Review,

Vol. 7, No.1), proclaims, "The psychosexual bottom line of most films by

Black male directors today is the desire

to replace the white man with a Negro

male who, while operating under the

guise of being a liberator, actually

internalizes the trappings and temperament of oppressor."

Gates, on the other hand, asks "Must

Buppiehood Cost Homeboy His Soul?"

(New York Times, March 1, 1992) and

insists that "[t]hese films argue that to be

upper middle class is to be alienated

from the 'real' Black community of the

gh etto. "

Are these guys talking about the same

movies? Salaam focuses on Boyz N the

Hood, Jungle Fever, Livin' Large and New

Organizational consultant D.T.

Saunders breaks it down clinically.

Members of a group reluctant to take

leadership watch a leader-like figure

emerge. They make a rigid separation

between the things they like and don't

like about this person. Out of fear that

these negative traits echo some of their

own, they magnify and denounce them,

in a ritual orgy of exorcism. Instead of

finding a composite gain in this

personality's pluses and minuses, they

jump to categorical put-downs, debilitating what might have led to a progressive

group effort. Saunders calls it an artjfact

of disempowerment. So the new jack

critics.

What better proof of the contagion of

new jack delirium than its temporary

(let's hope) outbreak in Kalamu ya

Salaam and Henry Louis Gates, Jr., two

experienced, very different cultural

commentators. Salaam apparently gets

Jack City. Gates' examples come from

Boyz N the Hood, Juice, Livin' Large,

Strictly Business and Ricochet. They both

speak as though they are talking about

"the new Black cinema." When they

talk about the same films, but see

diametrically different things, they seem

to be seeing what they want--or, more

importantly, what they don't want-to

see.

Veteran activist Salaam is furious at

Furious, Tre's dad in Boyz N the Hood.

He is not a positive image. Why?

Because he is "never shown working

with, not to mention organizing, his

community." Boyz N the Hood is about!

the notion that Black men have to take

the responsibility for making men of

their·sons. And Furious is drawn in very

direct, positive imagery as an example of

that. Salaam is talking about a different

movie and is measuring Furious against

a model he brought to the movie. So, he

finds Furious sadly lacking.

Gates finds an offensive portrait of

buppiedom in a scene in Juice where

Yolanda, the girlfriend of Quincy, the

protagonist, chooses him over a jacketand-tie dude. An assault on the Black

SPECIALIZING IN BLACK VIDEDS-middle class? Maybe the point of

Quincy's hook-up with Yolanda, who is

older than he and more socially mobile,

is to suggest his reach for possibilities

beyond his street partners' scams, a bit

like the Manhattan dancing partner of

John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever.

Both Salaam and Gates are dragging

issues into these films out of their own

frustrations,

asking them to measure up

I

to nonexistent scripts that would

@i

I

dramatize

their own social ideals favorRon Carter &-Art Farmer

Live at Sweet Basil's

Scintillating live jazz featuring 4 of the

ably. They score perceptive points, and

world's most respected musicians

even

their heavy, unbalanced dictums

CHILDREN'S Cooley High $7995 r - - - - - - - yR::F;-M_- - - - - - Who

I

---.!:~ANKYOU~FO~RO~RDERING~

are marshalled with intelligence and wit.

VIDEOS 95 Spook

Sat By The

$3995 I

People Could Fly $29

Door

I

==--=--==-~~_~~~~ ~----I But they lapse into criticism as personal

African Journey $79 95 Liberation Of $5995'

therapy.

$2995 L. B. Jones

, - - ----- --Words By

He

rt o

The pain and disorientation in the

'

$1995

----- r95

Monkey People $12

~~~:;r~~:~

$19

:

~J

-.=...

..

l,~21--~p_Oo,

community hits the writing

Black

95

Anansi The Spider $12 95 Come

I

lslt~.S1.00peroddtlO'1dt~ro<sHp/hO'1dlng. I I

community like a socio-political vertigo,

~~Z;~~~i~50

{

I

I

I Texosresldentsodd825~lox

I

I,

\;,o~~~:ro;~eA~~~~to5weeksfarde"very

Sen d $2 .00 for camp ete cata og

I0

iT~~:L_I'

a nightmarish confusion of nausea and

o

0

0

0

r - -, - _.-._. j

Alternative Videos

Da::.E;~~t~~~27

rage, a mood in which the venting of

-ALTERNATIVEVlDEOS..

QUANT

TITLE

-UNIT

TOTAL

PRICE

PRICE

N

ome

City

'..

#TAPES

AddUpsSJ.OO

SHIP/

Isttope&SIOOfo<eoch

Zip

- - - - - 1

Evening

I HAN"DL!

O'derswillbe filled and shipped UPS a'

SUB-

Check or money order enclosed

Amer Express

,

MasterCard

Cord#

Slgnotue

__..

VISA

Discover

Exp.Dote___

_

Black Film Review

_

LTOTALI

[214)823-6030

21

frustration is passed off as principled

pos trollS.. The critical response is to

focus one's target more sharply. More

often than not, that target is the

troubled knot of problematic identity

called Black manhood.

"My manhood?" asks 'Clay in Amiri

Baraka's play Dutchman. "1 didn't know

we were talking about my manhood."

And Lula, the white American know-itall replies, "What else do you think

we've been talking about all this time?"

Overselling his thesis that the new

movies locate authentic Black culture

only in the ghetto, Gates tries to make

an example out of Boyz N the Hood.

This should give him trouble, since

Furious, the father, is button-down

middle class, insisting on instilling

middle-class values into his son, who is

so afraid of being trapped in the ghetto

that he is afraid to lose his virginity, who

has the avenue of college education

drummed into him as the passage out of

the community-a remedial message

Salaam sensibly challenges.

How does Gates overcome this

obstacle? By reaching for the PC

feminist argument that the film attacks

"upper middle class women" in the

portrayal ofTre's mother, Reva. The

parental expertise of all Black women,

according to Gates, is threatened when

she turns T re over to his father because

she"can't teach him what he needs to

know." Whatever the merits of the

heated issues here, Singleton's pitch for

male-male parenting is not as debatable

as the counterargument that women can

always do it better.

Gates' defense ofbuppiedom against

ridicule in Livin'Large and Strictly

Business ignores the populist Hollywood

convention of satirizing the stuffed

shirts, who end up patting their feet at

the close of the movie. Nor does he

concede the tradition in Black expression, evidenced in Boyz N the Hood and

Juice, of directing attention to the most

oppressed sectors of the community, as

Frederick Douglass did when he at22

tacked slavery.

Salaam's critique of the sexism of the

new movies is adept, but overcommitted

to an either/or reading. There is a need

to examine Boyz N the Hood and Juice

differently from formula movies like

NewJack City and Livin'Large. Boyz N

the Hood and Juice aim to speak with

some honesty to the abject mental

vacuum that leads young Black men to

slaughter one another, arguably one of

the most difficult problems for any

Black speakers or leaders, let alone

filmmakers.

A movie that breaks with too many

existing movie codes will lose its audience. The parameters in which movies

like Boyz N the Hood and Juice get made

to reach young Black moviegoers with a

popular spectacle means making compromises that a critic ought to consider.

Boyz N the Hood does, as Salaam says,

depreciate the roles ofwomen. But

considering its intentions, that flaw need

not be "fatal."

New jack critics can be more formulaic than the movies they attack. Salaam

argues that Jungle Fever makes white

men "paragons of manhood" because

Paulie, a minor character, is portrayed

with some decency and sensitivity, while

Flipper, the central character in the

story, does not master his moral issues.

By this measure, John Singleton similarly sinned in Boyz N the Hood by

showing a Black cop acting more

brutally than his white partner. The

implied critical straightjacket would rob

directors of any chance to risk complexity, any right to probe the shaded,

human dilemmas of Black behavior, and

would rob Boyz N the Hood, Juice and

Jungle Fever of the weighty questions

they raise by going beyond positive

tmagery.

When a healthy Black fum culture is

achieved, let us hope it will raise politics

and the politics of representation as

crucial issues. But the bankruptcy of

positive-image criticism is its willful

blindness to the most basic practices in

Black Film Review

examining fictive, cultural works.

New jack critics lump serious and

huckstering movies together, without

regard for genre or predication. They

thrust all character and incidents

forward to a surface plane, flattening

them for easier PC scrutiny. Narrative

strategy is dismissed. Context disappears.

Positive image critics don't give a

damn about images, only characters, the

sociological look of them, and how they

might make "us" look, mainly to

"them." The meaning of a film is

avoided as a hindrance. Theme, intention, framing are frozen out, while the

new jack critics squint for texts to

sermonize their personal resentments.

Blaming the messenger for the message

is just a slight cut above holding actors

responsible for the fecklessness of the

characters they depict.

Rather than advance our understanding of how films work or how they

might contribute to a counterpolitic of

representation, new jack critics play to

the lowest critical perceptions in the

gallery. They follow the primitive

assumption that isolated images are

injected directly into the mainstream of

the viewer's consciousness, with no

meditations from story, multiple and

contrary significances-in short,

imagination.

New jack critics crawl out of the

woodwork as soon as a Black director

begins to achieve notoriety and fame.

Already, we can see this crabs-in-thebarrel criticism mounting against Julie

Dash and her success with Daughters of

the Dust. A friend of mine, a '60s radical,

said on the phone about that film, "1

was disappointed. 1 so wanted it to be

perfect." The fault, new jackers, lies not

in your stars but in yourselves.

Clyde Taylor is a professor ofliterature andfilm

studies at Tufts University and the author of

numerous articles on Blackfilm.

male body. When we see Chris in Young

continuedfrom page 11

Soul Rebels, we see a character who is

vulnerable on a number of levels.

these conflicting desires for identificaSimply, on the level of the plot, Chris is

tion-with Black men, with Blackness,

vulnerable to his lover Tracy. He needs

in general-at the center of Young Soul

her to satisfy his emotional and sexual

Rebels. The white character Ken's envy

needs as well as to help him make

of Black masculinity manifests itself in

inroads into the mainstream radio

the killing act. If the murder does not

industry. At the level of the image, Chris

make this explicit, the scene in which

is also vulnerable. He is framed throughKen fIXates on the mechanic Carlton's

out the fdm as the desired body-we see

body, as he takes a shower, certainly