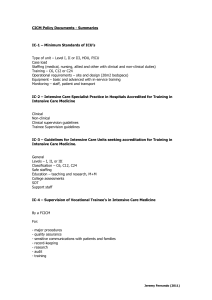

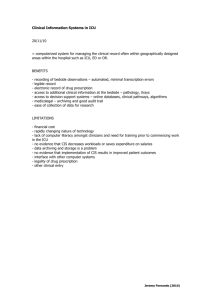

Review of Adult Critical Care Services in the Republic of Ireland

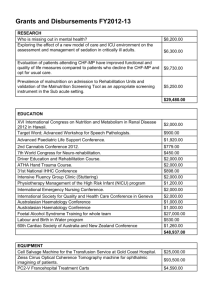

advertisement