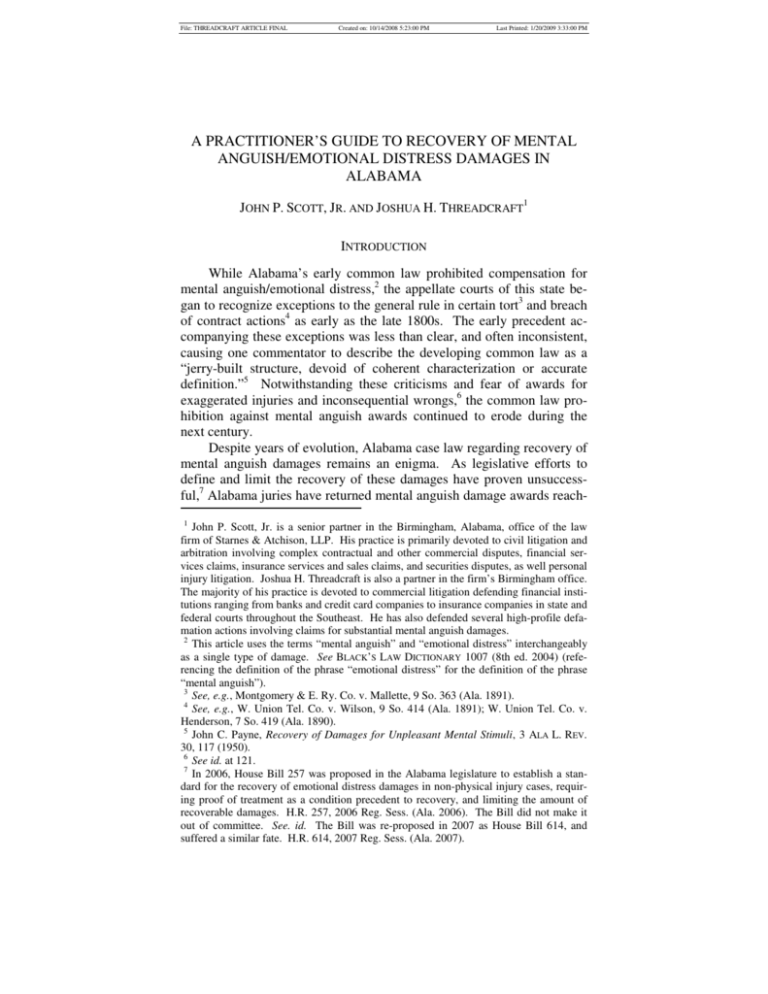

a practitioner's guide to recovery of mental anguish/emotional

advertisement