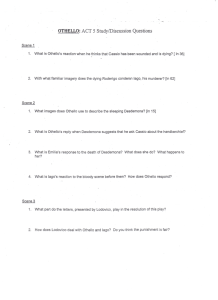

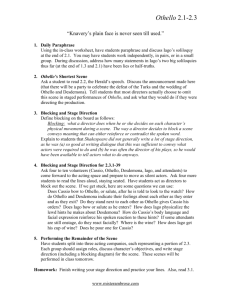

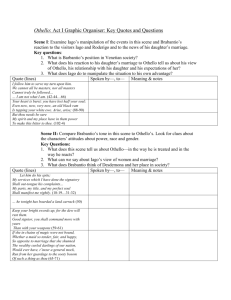

Othello background pack

advertisement