Modes of Gap Filling: Good Faith and Fiduciary Duties Reconsidered

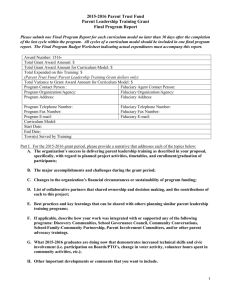

advertisement