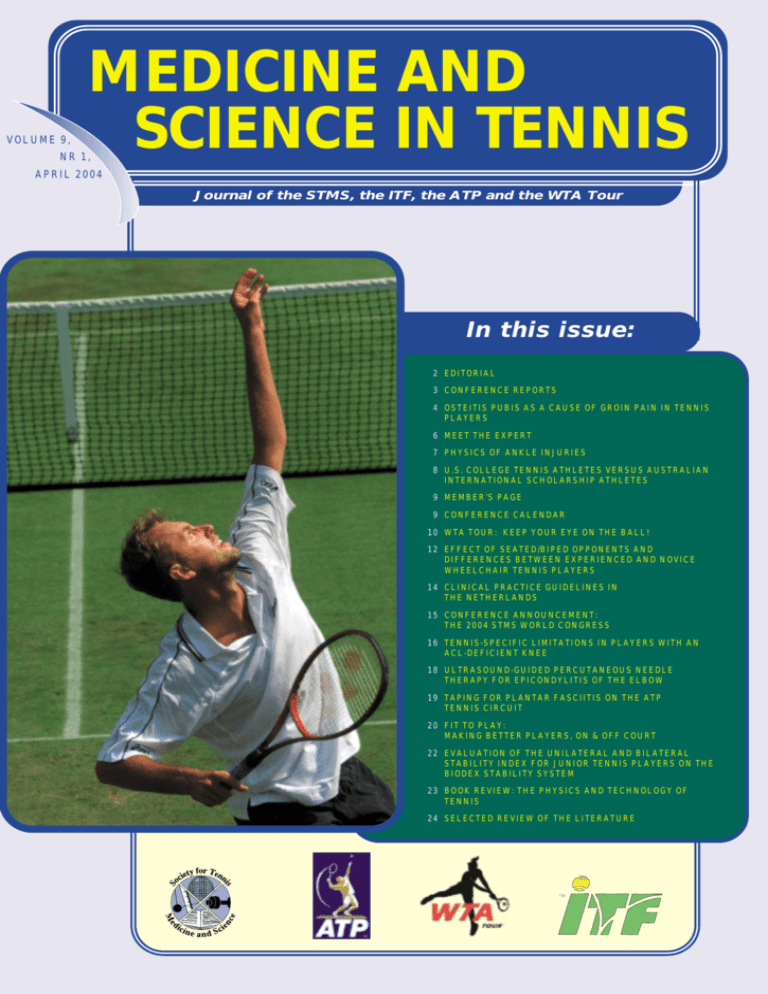

VOLUME 9,

MEDICINE AND

SCIENCE IN TENNIS

NR 1,

APRIL 2004

Journal of the STMS, the ITF, the ATP and the WTA Tour

In this issue:

2 EDITORIAL

3 CONFERENCE REPORTS

4 OSTEITIS PUBIS AS A CAUSE OF GROIN PAIN IN TENNIS

PLAYERS

6 MEET THE EXPERT

7 PHYSICS OF ANKLE INJURIES

8 U.S. COLLEGE TENNIS ATHLETES VERSUS AUSTRALIAN

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARSHIP ATHLETES

9 MEMBER’S PAGE

9 CONFERENCE CALENDAR

10 WTA TOUR: KEEP YOUR EYE ON THE BALL!

12 EFFECT OF SEATED/BIPED OPPONENTS AND

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN EXPERIENCED AND NOVICE

WHEELCHAIR TENNIS PLAYERS

14 CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES IN

THE NETHERLANDS

15 CONFERENCE ANNOUNCEMENT:

THE 2004 STMS WORLD CONGRESS

16 TENNIS-SPECIFIC LIMITATIONS IN PLAYERS WITH AN

ACL-DEFICIENT KNEE

18 ULTRASOUND-GUIDED PERCUTANEOUS NEEDLE

THERAPY FOR EPICONDYLITIS OF THE ELBOW

19 TAPING FOR PLANTAR FASCIITIS ON THE ATP

TENNIS CIRCUIT

20 FIT TO PLAY:

MAKING BETTER PLAYERS, ON & OFF COURT

22 EVALUATION OF THE UNILATERAL AND BILATERAL

STABILITY INDEX FOR JUNIOR TENNIS PLAYERS ON THE

BIODEX STABILITY SYSTEM

23 BOOK REVIEW: THE PHYSICS AND TECHNOLOGY OF

TENNIS

24 SELECTED REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

ISSN: 1567-2352

EDITORIAL

Medicine and Science in Tennis is a Journal produced by the Society

for Tennis Medicine (STMS) in co-operation with the ITF, the ATP, and

the WTA Tour, and is issued three times a year (April, August, and

December). The STMS is an international organization of sports

medicine and science experts aiming to serve as an international forum

for the generation and dissemination of knowledge of tennis medicine

and science.

Dear tennis friends,

I would like to welcome you all to the April issue of

Medicine and Science in Tennis. In this issue you will

find our first Members’ News page (page 9).

Members’ news is designed for members to let them

keep up-to-date on issues and events of interest to

STMS members. Members’ News is also the first step

towards increasing the benefits of being an STMS

member.

You can learn more about the medical ins and outs of the Wimbledon

Championships on page 6, where we introduce to you our medical

Wimbledon expert, Dr. Peter Tudor Miles. Peter has been the Medical

Director of the Wimbledon Championships for more than 25 years, and is

as familiar to Wimbledon Watchers as Strawberries and Cream. If reading

this interview has aroused your interest and you would like to visit

Wimbledon in person, do not hesitate! You can now sign up for our 2004

STMS World Congress, to be held in conjunction with the Wimbledon

Championships. You will be able to interact with world-renowned medical

experts in the field of tennis, and attend one of the first two days of the

Wimbledon Championships. Don’t miss it!

The spate of injuries at the Australian Open prompted two experts to look

into these matters more closely. Rod Cross focused his research on ankle

injuries in relation to the court surface and came up with both the cause

and the solution to these injuries (page 7). Dr. Tim Wood, Chief Medical

Officer of the Australian Open, discusses osteitis pubis as a cause of groin

pain in tennis players, and presents a very well-designed rehabilitation

programme (pages 4 and 5). More original research included in this issue

are: Dr. Marks’ study on physical performance profiling; the visual response

of wheelchair tennis players; limitations of tennis players with an

ACL-deficient knee and percutaneous needle therapy as a treatment modality for tennis elbow. The medical staff of the ATP and the WTA both contributed with very practical articles on eye protection and taping for plantar

fasciitis, respectively.

Currently, the WTA is conducting a 10-Year Review of the Age Eligibility

Rule. This 10-year Age Eligibility process is being spearheaded by the Age

Eligibility Advisory Panel, a panel of independent international experts in

the field of sports sciences and medicine. The panel has been advisory to

the WTA Tour regarding appropriateness of the current rule and the development of the programs with the ultimate goals being to promote career

longevity, fulfilment and the overall well being of players on the WTA

Tour. The four major components that comprise the 10-Year AER Review

include: a tennis wide survey, conducted by questionnaires and open forum;

data collection; medical literature review; and development of an evidencebased consensus statement that will be advisory to the WTA. The open

forum was held from 26th-28th March in Miami. In the next issue of

Medicine and Science in Tennis we hope to be able to present you the outcome of the Review.

THE INTERNATIONAL BOARD OF THE STMS

President:

Babette M. Pluim, Arnhem,The Netherlands.

Vice President:

Marc R. Safran, San Francisco,CA,USA;

Secretary:

Javier Maquirriain, Buenos Aires, Argentina;

E-mail: info@stms.nl

Membership Officer:

Alan Pearce, Melbourne, Australia;

E-mail: membership@stms.nl

Treasurer:

George C.Branche III, Arlington, VA, USA;

Past-president:

Per A.F.H. Renström, Stockholm, Sweden;

Other members:

Peter Jokl, New Haven, CT, USA;

W. Ben Kibler, Lexington, KY, USA.

Savio L-Y Woo, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Associates to the Board:

Miguel Crespo, Representative of the ITF;

Kathy Martin, Representative of the WTA Tour;

Gary Windler, Representative of the ATP.

North American Regional Committee:

Chairman: Marc R. Safran, San Francisco, CA, USA;

Peter Jokl, New Haven, CT, USA;

W. Ben Kibler, Lexington, KY, USA;

Michael F. Bergeron, Augusta, GA;

William Micheo, San Juan, Puerto Rico;

Carol L. Otis, Los Angeles, CA, USA;

E. Paul Roetert, Key Biscayne, FL, USA;

Savio L-Y. Woo, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

EUROPEAN REGIONAL COMMITTEE

Chairman: Giovanni di Giacomo, Rome, Italy, Chairman;

Gilles Daubinet, Paris, France;

Hartmut Krahl, München, Germany;

Hans-Gerd Pieper, Essen, Germany;

Babette Pluim, Arnhem, the Netherlands;

Angel Ruiz-Cotorro, Barcelona, Spain;

Michael Turner, London, United Kingdom;

Reinhard Weinstabl, Vienna, Austria.

SOUTH AMERICAN REGIONAL COMMITTEE

Chairman: Rogério Teixeira Silva, São Paulo,Brazil;

Javier Maquirriain, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE

Chairman: W. Ben Kibler, Lexington, KY, USA;

Michael F. Bergeron, Augusta, GA, USA;

Bruce Elliott, Perth, Australia;

Karl Weber, Cologne, Germany;

Savio L-Y. Woo, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

EDUCATIONAL COMMITTEE

Chairman: Marc. R. Safran, San Francisco, CA, Chairman;

George C.Branche III, Arlington, VA, USA;

Henrik Ekersund, Gothenburgh, Sweden;

Stacie Grossfeld, Louisville, KY,USA;

Peter Jokl, New Haven, CT, USA;

W. Ben Kibler, Lexington, KY, USA;

Kathy Martin, Melbourne, Australia;

Fernando Segal, Buenos Aires, Argentina;

Piotr Unierzyski, Poznan, Poland;

Gary Windler, Summerville, SC, USA.

Editorial Board:

Editor-in-Chief: Babette M. Pluim;

Todd Ellenbecker, Scottsdale, AZ, USA;

Javier Maquirriain, Buenos Aires, Argentina;

Rogério Teixeira Silva, São Paulo, Brazil

Alan Pearce, Melbourne, Australia;

Gary Windler, Summerville, SC, USA;

EDITORIAL OFFICE:

PO Box 302, 6800 AH Arnhem,

The Netherlands.

Phone +31-26-4834440

Fax +31-26-4834439

E-mail: editor@stms.nl

MEMBERSHIP OFFICE:

Alan Pearce, Ph.D.

C/o Tennis Australia

Private Bag 6060

Richmond South

Victoria 3121

Australia

T + 61 3 9286 1177

F + 61 3 9650 2743

E-mail: membership@stms.nl

Full membership: $100.00

Associate membership $ 50.00

Student membership $ 35.00

MEMBERSHIP PAYMENTS:

Commonwealth Bank of Australia

Richmond 242 Bridge Road

Richmond, Victoria, 3165

Australia

Routing # (BSB #) 063-165

Account # 10287882

PHOTOGRAPHERS:

Michael Kooren, Arjan Verbruggen

FRONT COVER:

LeAnn Silva, ATP, Ponte Vedra Beach, Fl, USA

CIRCULATION: 2,400

Babette Pluim, MD, PhD

President STMS

PUBLISHING OFFICE:

Modern BV, Bennekom, The Netherlands

WEBMASTER:

Ivo Wildeman, Hilversum, The Netherlands

E-mail: webmaster@stms.nl

Website: http://www.stms.nl

The newsletter ‘Medicine & Science in Tennis’ is supported by:

Disclaimer:

This journal is published by the Society of Tennis Medicine and

Science for general information only. Publication of information in the

journal does not constitute a representation or warranty that the

information has been approved or tested by the STMS or that it is

suitable for general or particular use. Readers should not relay on any

information in the journal and competent advice should be obtained

about its suitability for any particular application.

© 2003 Society of Tennis Medicine and Science. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without

prior written permission of the copyright holder. Opinions and research

expressed in this journal are not necessarily those of the STMS.

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 2

CONFERENCE REPORT:

12th Argentine Sports Medicine Conference

Tennis Science Symposium

T

Javier Maquirriain and Fernando Segal

he 12th Argentine Sports Medicine

Conference was held in Buenos Aires on

September15th. The scientific meeting was

organised by the Argentine Society of Sports

Medicine and the Gatorade Sports Science

Institute.

Dr. Juan Carlos Mazza, a renowned sports

scientist and chairman of the scientific

committee organised an interesting program including different sports-specific

sessions.

The Tennis Science Symposium was

co-ordinated by Javier Maquirriain (MD),

Argentine Tennis Association Medical

Director.

Professor Javier Capitaine opened with

“Physical conditioning for the elite tennis

player”. Capitaine is recognised for his

strength and co-ordination training

expertise. Professor Luis Erdociain then

presented an interesting lecture on

“Perception, attention and visual training

for tennis player” and psychologist

Fernando Vazquez lectured on

“Psychological profile of successful tennis

coaches”. The second part of the symposium began with the presentation

“Nutritional demands of the tennis player”

by Dr. Juan Carlos Mazza. Fernando Segal

(International tennis coach) presented the

final talk on “Developmental basis for

junior tennis players”.

High level of lecturers, interesting discussions and a one-hundred attendance

helped to constitute a successful scientific

meeting which also shows the growing

interest in Tennis medicine and science.

Sponsorship: Gatorade Sports Science

Institute, Temis Lostalo Laboratories,

Sevier Laboratories.

Australian Tennis Conference Report – 2004

he 9th Australian Tennis Conference

held just prior to the Australian Open

was a great success with about 300 coaches

and other industry professionals in attendance from around the globe. The theme of

this year’s conference was “Achieve More in

2004.” Several topics focussed on the competitive challenges our sport faces in the

21st Century. After a welcoming address

from the President of Tennis Australia,

Geoff Pollard, participants were treated to

an outstanding presentation from Jim

Stynes, one of Australia’s best Aussie Rules

players who focussed on the importance of a

coach’s role as a character mentor for young

people. Dan Santorum from the PTR then

followed and inspired us all with his talk

about The Coach - the key to tennis development. Another topic – The Coach – the

key to club success, was delivered by a panel

of selected successful coaches from around

Australia. A common theme that developed

from these sessions was the pivotal role

coaches play in developing grassroots tennis

and ensuring the future delivery of tennis to

all participants so it remains a major participation sport.

T

Canberra helped coaches themselves plan

recovery strategies to prevent burnout.

There were also a host of other tennis

coaching specialists.

During the traditional Conference Dinner

held at Royal South Yarra Tennis Club,

attendees heard from one of the legends of

Australian Tennis – Peter McNamara, who

kept everyone thoroughly entertained with

his recollections with life on the Tour

playing and coaching.

As in previous years, the calibre of presenters was world class. With a mixture of on

court sessions, workshops and indoor

forums, attendees saw presentations from

internationally renowned names such as

Professor Bruce Elliott who presented the

latest research in biomechanics, Miguel

Crespo from the ITF who provided an

entertaining session on court of psychological drills, Dr Ann Quinn helped us to

Prepare to Win, and Dr Paul Roetert from

the USTA taught us how to recognise and

develop potential and be dynamically flexible. Angie Calder from the University of

Feedback has been very positive and

thanks have been extended to the

Australian Tennis Conference Committee

who worked tirelessly to ensure another

success. Hope we can see you down under

in 2006 when our conference will be held

in conjunction with the Australian Open

and the STMS World Congress. Mark your

calendars now and come and enjoy some

great tennis and Aussie hospitality whilst

learning the latest research and coaching

methods from around the world.

Professor Bruce Elliott

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 3

ORIGI

RESE NAL

ARCH

Osteitis Pubis as a Cause of Groin Pain

in Tennis Players

DR TIMOTHY WOOD, CHIEF MEDICAL OFFICER OF THE AUSTRALIAN OPEN, E-MAIL GEORGEWOOD@BIGPOND.COM

uring this year’s Australian Open, two

tennis players (male) were diagnosed

with osteitis pubis. In both cases they had

had symptoms for more than six months

and one had had surgery to repair an

inguinal hernia, the presumed cause of his

pain. His symptoms had recurred as soon

as he resumed high intensity court work.

D

Groin pain is a relatively common complaint amongst tennis players and recently

the hip joint, and more specifically labral

tears, have been in the spotlight.3

Previously most groin pain has been attributed to pathology in the adductor tendons,

either acute or chronic or ‘occult’ inguinal

hernia.1 Whilst it is important to systemat-

ically check for all potential causes of groin

pain,2 it is important to include osteitis

pubis in that list. Whilst probably more

prevalent in sports which involve kicking,

e.g. soccer, where repetitive rotational

stresses are placed on the symphysis pubis,

tennis nevertheless does place significant

stress through this and surrounding structures.

The primary pathology in osteitis pubis

appears to be in the bone (GVerrall –

personal communication) which progresses

to involve the joint, including the cartilaginous disc, and may involve the multitude of

entheses in the region. These changes are

initially best appreciated on MRI, although

later CT scanning gives a better picture of

Figure 1 The squeeze test

the specific bony pathology.

Clinically the ‘squeeze’ test seems to give

the best reliability in diagnosing the condition. A clenched fist is held between the

knees at varying degrees of hip flexion and

the patient is asked to perform an isometric contraction of their adductors

(Figure 1). Two observations should be

noted. Firstly, the patient should state that

the manoeuvre reproduces their pain.

Secondly the examiner should note the

strength of the contraction. Many patients

will have very weak adductors if they have

had osteitis pubis for a significant period

of time. Alternatively a blood pressure cuff

inflated to 20 mmHg can replace the fist

and the maximal pressure reached by the

patient is measured. Normal pressures

achieved by asymptomatic individuals

would be expected to be above 120-140

mmHg. Chronic osteitis pubis sufferers

often can only achieve 60-80 mmHg

(DYoung – personal communication).

Local tenderness over the pubic bones is

thought to be too unreliable to use as a

test of osteitis pubis and is not recommended as a valid diagnostic finding.

Restricted hip internal rotation is thought

to be a risk factor for osteitis pubis in susceptible athletes (Figure 2).4

Once a diagnosis of osteitis pubis has been

made then a comprehensive rehabilitation

programme needs to be carried out. Such

a programme has arisen in Australia due to

the common prevalence of osteitis pubis in

Australian rules footballers (Table 1).

Strict adherence to it has yielded encouraging results but there are still players who

will struggle and some come to surgery to

debride the symphysis pubis. Newer treatments including intravenous bisphosphonates are currently being trialed.

In summary, in assessing a player with

groin pain, it is important not to forget

ostatis polio in the list of differential diagnoses. Early diagnosis allows the institution of an appropriate programme and

hopefully minimise time away from competition.

References

1. Gilmore J. Clin Sports Med 1998;17:

787-93

2. Lovell G. Aust J Sci Med Sport 1995;

27(3):76-9

3. Narvani A et al. Br J Sports Med 2003;

37:207-211

4. Williams J. Br J Sports Med 1978;12:

129-133.

Figure 2 Internal rotation of the hip

SPORTS MEDICINE

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Tim Wood is Chief medical officer of the

Australian Open since October 2001 and a

medical consultant to Tennis Australia since

2002. He is a member of Tennis Australia

anti-doping review board and member of

the ITF Sports Science and Medical

Commission. Dr. Wood is a sports physician

in fulltime private practice in Melbourne.

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 4

SPORTS MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 5

Isolation Trans

Abd & Pelvic Floor

Local Tissue

therapy

Core Stability

Knees apart in

(all planes)

Standing in

bilateral stance

Upper body

(sit, lying)

Not indicated

Sport specific

Challenge via

‘sliding’

Swiss Ball, Pilates

‘challenging’

The same, if

required

consider nsaids

Run alternate days

Stage 5

Controlled

Change of

Direction

Off Court - Gym

Single leg stance

Ease back as start

running drills

Glut max-squat

Adductors-pulley

On Court - Hit up

Short duration

Fitness testing

Set new goals

Increase effort

strengthendurance

Off Court - Gym

Start hitting up

Single leg squat

Lateral lunge

Self Massage

Sustained stretch

Practice warm up

Challenge via

balance

Fatigue resistance

Conditioning ++

Standard Recovery

(cold water etc)

Non-weight

bearing rest after

Session

Stage 6

Uncontrolled

Change of

Direction

Split lunge

Adductor Magnus

Massage adductor Massage adductors

before+/- after run

+/- TFL/Hip F/QL

Stretch the same

Stretch the same

Sideways shuttles

Walk, 1/2 squat

+ lateral movt.

Swiss Ball ‘easy’

Ice massage

adductor after run

100 m run thru

10 m accel/decel

Stage 4

Straight-line

Running

QL = quadratus lumborum

PNF = proprioceptive neuromuscular fascilitation

Cross train

Cycle/Versa etc

Swim

(pool buoy)

Not indicated

‘pain’

Cardio-vascular

fitness

TFL = tensor fascia lata

Hip F = hip flexors

Theraband

Adductors

Isometric

Adductors

Pain inhibited!

Muscle strength

PS = pubic symphysis

MVC = minimal voluntary contraction

Cont Massage

Stretch Hip F,

hams,quads, calf

Add Massage of

TFL, Gluts

Single leg stance

Inner unit + single

leg stance

Ice, PNF

Massage

Adductors

Squeeze the ball

Inner unit

(sit, stand, lie)

Muscle length

(don’t stretch

adductors)

Low MVC

Co-contraction

Nsaids,

ice massage

electrotherapy

Unload

Abd-Add

Synergy

Keep knees

together

Pelvic sacro iliac

belt

Reduce adductor

tone

Modules

Stage 3

Exercise out

of PS neutral

If delayed,

If settle slowly,

consider prolotherconsider infiltration

apy

Stage 2

Exercise in

PS Neutral

Stage 1

Unload & Local

Tissue Therapy

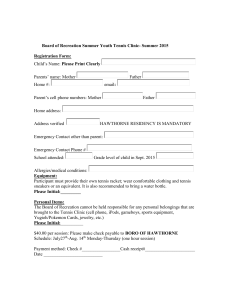

Table 1 Example of Conservative Rehabilitation for Osteitis Pubis for Tennis – Adapted from Hogan (personal communication)

Be aware of

fatigue/pain

Limit running to on

court ie don’t run

to get fit

Taper off

Massage before

and after training

Include in

warm-up

Maintain inner

unit awareness

No nsaid masking

Plan recovery days

Stage 7

Resume

Training

MEET THE EXPERT

Dr Peter Tudor Miles

MEDICAL DIRECTOR, THE CHAMPIONSHIPS, WIMBLEDON

CHIEF MEDICAL ADVISOR, THE ALL ENGLAND LAWN TENNIS CLUB (AELTC)

and ultrasound scans. They bring a

color enhanced, state of the art ultrasound scanner on site and take the

images and interpret them in front of

the players and doctors. The MRIs,

radiographs, and isotope scans are done

off site.

My role is to provide general medical

services ( non-injury) care to players,

and for key tournament staff. There are

around 6000 temporary staff. I also run

the whole medical team administration.

There are two nurses who act as nurse/

receptionists. There are also two remedial gymnasts. They supervise the gym

and provide some educational input to

players/coaches and managers (who

often need some guidance on best

practice in using the gym/equipment) .

Dr. Peter Tudor Miles

last of a series of four interviews

doctors who work for the grand

Islamnwiththetournaments,

Medicine and

Science in Tennis talks to Peter Tudor

Miles. Dr. Tudor Miles has recently

announced his retirement from General

Practice and from his role as the

Medical Director for the Wimbledon

Championships. He has co-ordinated

and managed the medical cover for

Wimbledon for over 25 years and is as

familiar to regular Wimbledon

Watchers as Strawberries and Cream.

1. What is your specialty?

Family medicine. I have been a

Principal in a family medicine practice

since 1972 in Wimbledon Village and

Senior partner since 1986. This is a

group practice with five partners. It is

also a training practice and I was the

accredited trainer.

I was first Secretary and then Chairman

of the South London Faculty of the

Royal College of General Practitioners (

350 members).

2. For how long have you worked as a

tournament doctor?

Twenty eight years. I was the only doctor at the Grand Slam Wimbledon for

players from 1975 -1999 inclusive. In

1999-2000 I had the opportunity with

the Tournament Diector to build a

team as the All England built the players and Members a new £ 20,000,000

pound facility with a new medical

centre.

We appointed two full time Sports

Medicine specialists (Mark Batt and

Philip Bell) and two radiologists who

report all the plain radiographs, MRIs

3. What is your regular job?

I retired as a Family Physician in March

2003.

4. Which tournaments do you cover?

The All England Championships only.

In the 1970s and early 1980s I did provide medical cover for the English

Davis cup team when playing at home

on a number of occasions and the

Wightman Cup

(USA versus UK, ladies ) for home

events but not in the USA. I covered

no other tennis events.

5. How did you first become involved

in providing medical cover for

tennis tournaments?

I stood in for a sick colleague at

Wimbledon and I suppose the All

England decided they could put up

with me!

6. Are you responsible for the general

public as well?

No, I am not responsible for the public.

The public are cared for by a separate

team of volunteers from St John’s

Ambulance organisation. Each day,

there are two doctors and around 15

nurses.

7. What changes have you made over

the years that have had the greatest

positive impact on care for players at

tournaments?

The appointment of a comprehensive

team in 2000, in new premises. Now

we have two full time sports physicians,

two radiologists, two nurse/receptionists, and a chiropodist/podiatrist, two

remedial gymnasts, in addition to the

pre-existing complement of physiotherapists.

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 6

8. Do you foresee any significant

changes in the future in terms of

care for professional tennis players

at tournaments?

Yes, If possible for faster rehabilitation

through the agency of enhanced physical therapy. The possibility to provide

individual players with some educational input on injury prevention in collaboration with coaches/managers. Time

would be a problem!

9. Is there a difference in the medical

care of male and female athletes?

Difficult question. The factor that

mainly springs to mind is the relative

immaturity of some very young female

athletes who need great sensitivity in

approaching their problems and often

acting as an advocate for them.

Coaches, managers and families may

load unreal expectations and pressures

onto the athlete.

10. What is the most interesting

medical problem you have

encountered?

The one that caused the most tension

pre-event was gender assignation. A

male karyotype who put in an entry for

the ladies singles. It was decided on the

karyotype that this applicant was male

and could not compete as a female

despite his/her gender re-assignation/

surgery etc.

On court, a suspected re-entrant tachycardia re-occurence was in a men’s

semi-final on court when the players

felt faint and had to come off court for

evaluation. He had had a cardiac ablation procedure for a previous event and

we and the ATP medical teams were

quite unaware of this! The ATP medical

data protocols at the time allowed for

no prior notification of any pre-existing,

potentially serious/fatal illnesses to be

communicated to tournament physicians. This was felt then to be a possible

breach of confidential medical information if provided.

I argued with the ATP medical committee that this information should be

made known to the doctors responsible

for player medical care (in confidence)

for safe medical care .

Only information on serious illness

which might require emergency medical action, so called “ Red Flag events “

The ATP have actioned this. Players are

now sent an annual questionnaire

specifically asking them to give the ATP

medical teams any new/changing information re: “ Red Flag events”.

ORIGI

N

RESE AL

ARCH

Physics of Ankle Injuries

ROD CROSS, PHYSICS DEPARTMENT, SYDNEY UNIVERSITY, SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rod Cross is an Associate Professor in

physics at Sydney University and co-author

of the book The Physics and Technology of

Tennis with Howard Brody and Crawford

Lindsey (see photo). His main research

interest is the physics of tennis equipment.

A more recent interest is the physics of

falling off cliffs and high buildings.

shows that a vehicle is more likely to roll

over as it rounds a bend if it has a high

centre of gravity and a narrow wheel base.

Similarly, a tennis player (or a soccer player or a basketball player) is more likely to

roll the ankle if the shoe is narrow or has a

thick sole (raising the centre of gravity) or

if there is a high COF between the shoe

and the court surface. The vertical reaction force from the court acts up through

the middle of the shoe when a player is

standing upright, but it shifts towards the

outside edge of the shoe if the player

pushes down and sideways. If the player

pushes hard enough the reaction force

shifts to the extreme outside edge. Any

harder and the foot will roll.

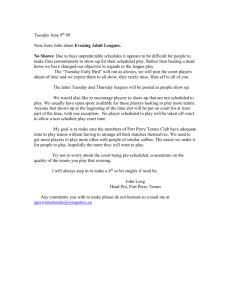

Rod Cross, Crawford Lindsey and Howard Brody

he spate of ankle injuries leading up to

the Australian Open this year prompted a lot of comment concerning the fact

that Rebound Ace becomes sticky in hot

weather. The physics of this is quite interesting and is illustrated in Figure 1. If a

player pushes down and sideways on a

shoe then there are several possible outcomes, including the fact that the foot can

roll or tip over as illustrated. The vertical

component of the force is opposed by a

vertical reaction force from the court, and

the horizontal component is opposed by

the friction force acting between the shoe

and the court. If these forces are in balance

then the shoe can’t move vertically and it

can’t move horizontally. The shoe might

still be able to rotate, but under normal

conditions the total torque (due to the

various forces on the shoe) will also add

up to zero. However, if the force on the

shoe is big enough then the shoe will

either slide along the court or it will roll

over, depending on the coefficient of

friction (COF) between the shoe and the

court.

T

over depending on where you push it. The

packet will slide if you push it near the

bottom but it will probably tip over if you

push it near the top (as in Figure 2). It will

certainly tip over if there is a large COF

between the packet and the table. The

mathematics and the physics of this shows

that the packet tips over more easily if the

COF is large, or if the packet has a high

centre of gravity, or if the packet is relatively narrow. The same mathematics

Figure 1

On a clay court the COF is small since

small particles under the shoe act a bit like

ball bearings, and the shoe will slide. The

COF between a tennis ball and a clay

court is actually very large, which is why

clay courts are so slow, but the COF is

small between the court and a shoe. On a

rough-textured hard court the COF is

large and there is a much greater chance

that the shoe will rotate about the outside

edge, with unpleasant consequences.

The difference between sliding and rolling

is easily demonstrated with a packet of

cornflakes on a table. If you push sideways

on the packet, it will either slide or tip

Figure 2

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 7

Conclusion

Inventing better shoes based on these principles is unlikely to be very profitable.

Such shoes would suit mainly top players

competing on hard courts. Average players

and many professionals make the mistake

of wearing the same type of shoe on all

surfaces. Top players don’t ask how much

shoes cost. They ask how

much they will be paid to wear them.

ABST

Physical Performance Profiling:

RACT

U.S. College Tennis Athletes versus Australian

International Scholarship Athletes

BONITA L. MARKS, PH.D., FACSM, ELIZABETH W. GALLEHER, B.S., MIKIKO SENGA, B.S, LAURENCE M. KATZ, M.D., FACEP

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA AT CHAPEL HILL, DEPTS. OF EXERCISE AND SPORT SCIENCE AND EMERGENCY MEDICINE,

CHAPEL HILL, NC 27599-8700, E-MAIL MARKS@EMAIL.UNC.EDU

he physiological demands of competitive tennis necessitate the training of both the anaerobic and aerobic energy systems for optimal

tennis performance. Despite this knowledge, there is a surprising paucity of published information about the physical fitness and skill

attributes of competitive tennis players at the U.S. college level. Therefore the purpose of this study was to determine how U.S. college

tennis athletes compared to an international group of competitors. Twenty U.S. college tennis players (11 M, 9 F, 18-23 years old,

average age = 19.5) were invited to participate in a series of evaluations. The U.S. athletes completed university-approved research

participation consent forms. Published performance results from the AIS Tennis Program were used as the comparison group (n = 19;

7 males, 12 females; age: 16-19 years old). Two-tailed Student T-Tests were used to determine significant differences between the

published AIS Tennis Program scores vs. the U.S. scores:

T

Variable

Height (cm)

Body Mass (kg)

Body Fat (%)

Hamstring Flex.(cm)

VO2max (ml•kg-1•min-1)

Vertical Jump (cm)

5 m Sprint (s)

10 m Sprint (s)

Spider Test (s)

Overhead Throw (m)

Lf. Sidearm Throw (m)

Rt. Sidearm Throw (m)

Flat Serve (mph)

U.S. Men

AI.S. Men

180.6 ± 4.6

76.9 ± 7.6

8.2 ± 3.5

45.2 ± 7.3

61.0 ± 4.5*

53.0 ± 9.9**

1.3 ± 0.2**

1.9 ± 0.1

17.1 ± 0.9

12.2 ± 1.3

13.2 ± 0.7**

14.7 ± 1.4*

107.1 ± 3.4**

184.6 ± 6.8

79.2 ± 6.9

7.8 ± 3.0

n/a

56.9 ± 4.8

66.4 ± 9.2

1.1 ± 0.1

1.8 ± 0.1

16.8 ± 1.1

11.9 ± 1.2

16.3 ± 1.7

16.7 ± 1.4

96.7 ± 3.7

U.S. Women

166.1 ± 5.2 [n=3]

58.0 ± 6.4 [n=3]

19.1 ± 5.1 [n=3]

49.8 ± 4.9

n/a

41.8 ± 5.9**

1.3 ± 0.2

2.1 ± 0.2

19.5 ± 1.1**

6.7 ± 0.8**

8.0 ± 0.7**

8.6 ± 0.8**

91.7 ± 5.1*

A.I.S. Women

170.0 ± 5.5

64.9 ± 6.1

18.9 ± 3.5

n/a

55.8 ± 3.3

50.1 ± 5.2

1.2 ± 0.1

2.0 ± 0.1

17.4 ± 0.5

9.5 ± 1.4

12.1 ± 1.3

12.3 ± 1.2

85.7 ± 3.8

* Statistically significant difference, p < 0.05; ** Statistically significant difference, p < 0.001

In conclusion, even though the teams of these particular U.S. college tennis players were ranked among the top 25 NCAA Division I

Tennis Teams, with the exception of the flat serve, this data suggests that the U.S. players could benefit from more specific anaerobic

training. Conversely, the U.S. males were more aerobically trained. A larger, more diverse collegiate sample would be needed to determine how widespread these performance outcomes were nationwide.

Figure 1 Subject performs the sit

and reach test to determine lower

back/hamstring flexibility

Figure 2 Subject demonstrates

a side-arm throw with a 2-kg

medicine ball

Figure 3 Subject prepares for one

of 12 service attempts

Figure 4 Subject having his

quadriceps fatfold measured for

body fat estimation

FROM

LITER THE

ATUR

E

Effect of Type 3 (Oversize) Tennis Ball

on Serve Performance and Upper Extremity Muscle Activity

BLACKWELL J, KNUDSON D

UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA, USA

Sports Biomech 2002;1(2):187-92

his study investigated the effect of the

larger diameter (Type 3) tennis ball on

performance and muscle activation in the

serve.

T

Sixteen male advanced tennis players performed serves using regular size and Type

3 tennis balls. Ball speed, surface elec-

tromyography, and serve accuracy were

measured. There were no significant differences in mean initial serve speeds

between balls, but accuracy was significantly greater (19.3%) with the Type 3

ball than with the regular ball. A consistent temporal sequence of muscle activation and significant differences in mean

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 8

activation of different muscles were

observed. However, ball type had no effect

on mean arm muscle activation. These

data, combined with a previous study, suggest that play with the larger ball is not

likely to increase the risk of overuse injury,

but serving accuracy may increase compared to play with the regular ball.

MEMBER’S NEWS

Society for Tennis

Medicine and Science

From the Membership Office

I would like to welcome you all to

the first Member’s News page.

Member’s News is designed for

members to keep communicated on

issues and events of interest to

STMS members. Member’s News is

also the first step in creating

greater benefits of being an STMS

member.

We are aiming to have Member’s

News included in each issue of the

Journal of Medicine and Science in

Tennis. However, if demand for

more updates increase, we will

certainly look at having Member’s

News as an email service for

members

Member’s News will be light and

informal in content, however, it will

not be limited to one page.

We encourage members to send

contributions of related events they

wish to publicise, and the more

news and information we have to

distribute, the better I say!

Welcome

New

Members

Mr Richard Bricknell

Mr David Lovejoy

Dr Sharat Kumar Paripati

Please send your contribution of

news and/or information to the

Membership Officer on

membership@stms.nl

I look forward to you contributions!

Mr Carl Petersen

Ms Kristel Schuffelers

Dr Timothy Wood

Dr Atushi Akaike

Dr Shuzo Okudaira

Alan Pearce, PhD

Dr Bonita Marks

Dr Iwasaki Takaaki

THE BENEFITS OF BEING AN STMS MEMBER

STMS was founded as an international

organisation of sports medicine and

science experts aiming to serve as a

forum for the generation and dissemination of knowledge of tennis

medicine and science.

• Opportunity to acquire fellowship

status for services to the STMS

Full Membership benefits include:

• Subscription to three issues per year

of the Journal Medicine and Science

in Tennis

• Subscription to three issues per year

of the Journal Medicine and Science

in Tennis

• Dedicated member area

CONFERENCE CALENDAR

Please feel free to let other members know of

conferences, seminars, workshops in your

country

19-20 J UNE 2004

6th International Conference on Medicine

and Science in Tennis. Held in conjunction

with LTA Sports Science and Sports

Medicine Conference, London, UK

Information: Dr Michael Turner

Michael.Turner@LTA.org.uk

14-16 A PRIL 2004

Australian Association of Exercise and

Sports Science 2004: From research to practice inaugural conference will be held at

Queensland University Technology,

Australia

Information: www.aaess2004.qut.edu.au

13-16 S EPTEMBER 2004

5th International Conference on the

Engineering of Sport. University of

California, Davis, USA

Information: isea2004@cislunar.com

Associate and Student benefits

include:

• Discounts to STMS meetings

JSMS Tennis Edition

After contact with Sports Medicine

Australia, STMS have some good news

regarding the Journal of Science and

Medicine in Sport (Tennis Edition).

A number of members have enquired

receiving a copy. However with

Dr Alan Pearce changing employment,

records of those who enquired

purchasing a copy were lost in the

move. This is regrettable and STMS

apologises for any inconvenience

caused. If you still wish to have a copy

we are continuing the offer of US$10

per copy (plus postage). Stocks are

limited and this will be the last of the

stock.

Enquires to Dr Alan Pearce on

alpearce@bigpond.net.au

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

Mr Fernando Segal

Ms Nell Mead

Congratulations . . .

• STMS voting rights

• Discounts to STMS meetings

• Entitlement to use the STMS nomenclature (MSTMS)

Dr Masahiro Horiuchi

TENNIS 9

Congratulations on STMS member

Prof Bruce Elliott who along with Dr

Miguel Crespo and Macher Reid

recently published the ITF Advanced

Biomechanics of Tennis. From all

accounts the text has been well

received internationally.

WTA

WTA Tour: Keep your Eye on the Ball!

KATHY MARTIN, SPORTS PT, AND LAURA EBY, PT, ATC, WTA TOUR, ONE PROGRESS PLAZA, SUITE 1500,

ST. PETERSBURG, FL 33701, USA

eeing the ball clear and sharp is a necessity for top tennis performance.

Educating players about the benefits of,

and encouraging players to adopt the practice of wearing protective eyewear is part

of the preventative, performance enhancing health care process in which the

Primary Health Care Providers of the

WTA Tour engage.

S

The first step in any education process

with tennis players is to provide the facts

in an easy to understand format. With that

aim in mind, the WTA Tour produces a

monthly education topic, ‘Physically

Speaking’ that targets key issues for young

women professional tennis players. The

topics are available at every WTA Tour

event, are posted on the WTA Tour player

extranet, as well as being emailed to players and other key members in the players’

support group, e.g. coaches. The topic of

eyewear for tennis was covered in 2003.

The challenge in this instance is presenting

the material in a way that will influence

and impact upon the prevailing culture.

Within that culture, it is a firmly

entrenched idea that sunglasses are fashion

items only. Tennis players are notorious

for wearing UV protective eyewear everywhere except on the court during matches

and practice!

There is an enormous amount written

about the dangers of exposure to UV

radiation. Most tennis players are aware of

the need for sun protection for the skin in

terms of wearing a hat and application of

sun block. Information collected during

the annual WTA Tour physicals would

indicate that players are increasingly wearing a hat to play and applying sun block to

their face routinely. Less frequently, they

apply sun block to other areas of exposed

skin on the body. It is rare, however that

players are aware of the potential eye

damage related to UV radiation and of the

protective effects of wearing sunglasses;

even rarer is a player who plays tennis in

protective sunglasses.

The sun gives off different types of radiation, including: visible light/sunlight and

invisible radiation known as ultraviolet

radiation, or ‘UV’. It is well documented

that UVA and UVB rays are harmful to

the skin but UV can also have disastrous

effect on the eyes. Eye damage from UV

exposure can include: cataracts, a gradual

clouding of the lens of the eye that leads

to loss of vision; various cancers of the

eyelid and skin around the eye; macular

degeneration, an eye disease that causes

damage to the central retina and is the

leading cause of blindness; and photokeratitis, a painful sunburn of the cornea or

surface of the eye. Reflected sunlight is a

common causative factor in development

of photokeratitis. Reflection from concrete

(e.g. tennis stadiums) is particularly dangerous. Staring directly at the sun can also

permanently scar the retina, and lead to

vision loss. Players must be cautioned

about these risks.

Eye disorders in tennis players are caused

by UV exposure and chronic eye irritation

from dry, dusty conditions. Two of the

most frequently seen are:

1. Pinguecula, which is a yellowish patch

on the white of the eye, usually on the

side nearest the nose, that generally

does not affect vision.

2. Pterygium, which is a fleshy tissue

growth that grows over the cornea of

the eye that can decrease vision.

Pterygia are common in tennis and can

progress from being merely unattractive to occluding vision. The only way

to correct the problem once it is in situ

is to have the tissue surgically removed.

The chances of a pterygium returning

with increased damage are high. Players

post surgery need at least two months

rest; no sun exposure and they must

wear sunglasses for the surgery to have

any chance of success. The only way for

pterygia not to get worse (with or without surgery) is to wear 100% UVA and

UVB protective sunglasses. There is

definitely a case for player education

and to encourage players to wear UV

protective sunglasses.

Eye damage caused by the sun is cumulative and there is evidence to suggest that

children are particularly at risk, due to the

clarity of their lens structure that permits

greater UV and low wavelength (violetblue) visible light penetration than an

adult lens. It is estimated that up to 80%

of the lifetime cumulative UV exposure

occurs before a person reaches 20 years of

age.5 For this reason it is critical that

player education begins early, ideally at

the junior and ITF circuit level.

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 10

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Kathy Martin was the Australian Olympic

Team Physiotherapist in 2000, the

Australian Fed Cup Team Physiotherapist

from 1994 to 2000, and Sports Medicine

Consultant to Tennis Australia from 1998 to

2003. She joined the Tour as a Primary

Health Care Provider in 1991. Her current

positions with the WTA Tour include the

Professional Development Department,

Coordinator of the Athlete Assistance

Program, the ‘Partners for Success’ Mentor

Program, the Career Development Program,

and the Player Education Program.

Laura Eby graduated from the University of

Connecticut and became a licensed and certified Physical Therapist / Athletic Trainer in

1989. She has worked for the WTA since

January 1998 as a Primary Health Care

Provider, including two years as Manager of

the Sport Sciences and Medicine Department (2000-2002). Laura’s continuing education in physical therapy has included the

areas of manual therapy, muscle energy,

myofascial release, craniosacral and osteopathic techniques.

To minimise solar radiation exposure of

the eye, ophthalmologists recommend that

sports participants wear an appropriate

sunscreen of Sun Protection Factor 15 or

higher; a hat with a brim to shade the face

and eyes; and appropriate sunglasses. To

protect the eyes and reduce damage

caused by dry atmospheric conditions,

eye-wetting solutions may also help.

The two components of sunglasses, the

frames and lenses, come in an array of

choices.

Frames:

Advise players to select frames that incorporate high performance technology, are

lightweight, and impact resistant. For the

best fit, frames should cover the entire eye

socket, fit close to the face, and come with

padding and non-slip components at the

temple/bridge of the nose. Elasticised

bands work best to hold the frames in

place. The frames should allow the player

to have clear peripheral vision. Wraparound frames offer almost complete UV

protection, whereas regular frames still

allow 5% UV to reach the eyes. Nylon and

plastic are lightweight and are the most

common sport frames. Metal can also

work well. For prescription sunglasses, a

player may be more limited on frame

selection, as some wrap-around frames do

not work well with prescription lenses.

Lenses:

If a player requires prescription glasses,

make sure that they are also wearing prescription sunglasses. Many players’ eye

exams during the annual WTA Tour physicals indicate that they have less than

20/20 vision. Although all these players

are recommended to consult with a qualified optometrist, sports vision optometrist

or ophthalmologist for further testing and

prescription of corrective lenses, many do

not. There is still a culture within professional tennis that discourages the wearing

of any types of lasses. The reasons given by

players relate to: perceived discomfort,

especially in relation to movement of the

glasses with sweating; unfamiliar with

wearing glasses; and the potential for

decreased peripheral vision. This remains

one of the challenges the Primary Health

Care Providers try to overcome when educating the players. Players are reminded

that optimal visual ability directly relates

to on court performance.

All sunglass lenses should be ‘optically

ground lenses’ to provide the clearest

vision. Polycarbonate lenses are super

strong and the only true impact resistant

material for sport; important factors that

will assist in protecting the eye from traumatic injury if direct impact were to

occur. A tennis ball may impact the eye at

immense speeds, up to 200 km/h

(120 m/h) on a serve. That ball is like a

missile if it hits the eye and can cause

debilitating damage that may end a promising career.

There are many varieties of lens available

on the market, some of which are considered below. It is critical that a knowledgeable practitioner directs players to an

appropriate product for tennis.

Ultraviolet Ray (UV) Protection: This is a

must for all tennis players. The American

Academy of Ophthalmology recommends

that sunglasses should block out 99-100%

of UVA and UVB rays for proper eye

protection. Players must be instructed to

check the UV protection information on

the label before buying sunglasses. Players

who wear contact lenses with inherent UV

protection are still recommended to wear

UV protective sunglasses.4 The American

Academy of Ophthalmology advises that

the protective benefits of UV absorbing

contact lenses against UV exposure has

not been established. More research needs

to be done.

Polarisation:

This reduces or eliminates the reflective

glare of surfaces such as a tennis court and

the stands. Polarisation changes the colour

of the lens but it does not protect the

wearer from UV radiation. Players need to

be aware to check the lens is polarised and

provides sufficient UV protection.

Tint:

Tinting is frequently applied to lenses for

the purpose of filtering certain wavelengths of light through the lens, to

improve visual acuity and enhance the

clarity of other colours in the spectrum.

Manufacturers of sunglasses market a blue

tinted lens for tennis, claiming this provides an increase in colour contrast

between the yellow of the tennis ball and

the background of the court. However,

players must be educated that there will

be no benefit when playing on any court

with a greenish or blue green surface, e.g.

most of the hard courts, most of the

indoor courts, the green clay of the USA

and grass courts, where the colour contrast

is questionable how beneficial they are for

tennis players, and most practitioners view

them as a cosmetic option.1

Photo chromatic lenses:

These will lighten or darken depending on

the amount of light present. They may

provide sufficient UV absorption, but as it

takes time for them to adjust to changing

light conditions, they are unlikely to be

effective for tennis players outdoors where

the light conditions can change dramatically in a matter of moments.

may actually be reduced with this kind of

lens. At best, these lenses will provide

improved colour contrast on a red clay surface.3

Additionally, there are concerns about

what effect a blue lens tint has on UV

exposure. Recommendations form the

American Academy of Ophthalmology

indicate that additional retinal protection

is provided by lenses that reduce the transmission of violet-blue visible light. There is

concern that both near-UV and visible

blue light may contribute to macular ageing and degeneration. Blue lenses do exactly the opposite: they admit the violet-blue

end of the light spectrum, and potentially

may be creating more eye damage. With a

blue lens, much of the bright long wavelengths (yellow) end of the light spectrum

is blocked, and the player perceives the

world to be darker. This can result in a relatively dilated pupil, which will increase

the exposure to short (blue) wavelength

light than without any sunglasses. There

may be added risks of blue lenses with

children, due to the higher transmission of

short wavelength light permitted in to the

lens of a young eye.3 It is recommended

that advise about lens tinting for tennis

only be given by a qualified optometrist,

sports vision optometrist or ophthalmologist who is fully conversant with the

impact of tint.

Anti-Reflective Coatings:

These can be another useful choice for

tennis players. In prescription eyewear,

these are used for cosmetic purposes; the

coating makes the lens look thinner, and

reduces the reflection caused by a thick

lens. In sports sunglasses, an anti-reflective

coating helps to reduce glare by decreasing

the reflected light that enters from behind

the sunglasses wearer and bounces off the

lens into the eyes. It is best applied to the

surface of the sunglasses that is nearest the

eye.1

Mirror Coating:

These can provide some additional reduction in intense glare and may be useful in

bright sun situations, like snow skiing.2 It

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 11

Educating players on the potential risks of

eye damage from exposure to UV radiation and of the potential protective benefits of sunglasses is critical to the players’

eye care, visual acuity and ultimately

impacts upon their on-court performance.

The inclusion of advice and guidance by

qualified optometrists, sports vision

optometrists or ophthalmologists who are

fully conversant with the needs of professional players is part of the education

process. A significant paradigm shift needs

to occur among professional players before

routine wearing of protective eyewear during training and competition is adopted.

The Primary Health Care Providers of the

WTA Tour have begun the process to help

the professional women players make this

change and to adopt better preventative

eye care habits.

References

1. DeFranco L. Do you need lens

coatings? In

www.allaboutvision.com/lenses/

coatings.htm, 2003.

2. Dunleavy BP. Lens choices. Sport

Specs 2003;20:88-89.

3. Marmor MF. Double Fault! Ocular

hazards of tennis sunglasses. Arch

Ophthalmol 2001;119(7):1064-1066.

4. Vinger PF. A practical guide for sports

eyewear protection. Phys Sports Med

2000;28(6).

5. Young S and Sands J. Sun and the eye:

Prevention and detection of lightinduced disease. Clin Dermatol

1998;16:477-485.

Effect of Seated/Biped Opponents and Differences between

Experienced and Novice Wheelchair Tennis Players

RAÚL REINA VAÍLLO,1 FRANCISCO JAVIER MORENO HERNÁNDEZ,1

DAVID SANZ RIVAS2 AND VICENTE LUIS DEL CAMPO1

1 University

of Extremadura, Faculty of Sport Sciences. Laboratory of Motor Control and Learning, Spain

Tennis Federation, Avenida Diagonal 618 2º 2ª, Barcelona 08021, Spain

2 Spanish

O

ne of the objects in studying the visual

behaviour in sport situations is to find

and to establish relationships between the

level of the athlete’s visual skills and his sport

performance.4 Nevertheless, this research

topic has not been extensively explored in the

area of players with disabilities.12 Some studies suggest that a successful performance

requires as much ability in perception as it

does in precise execution of the movement.1,16,20,21 The ability to perceive events

quickly in complex sports situations is an

essential requirement for a skilled performance.

In sports like wheelchair tennis, the player’s

motor response is determined by a temporally

limited situation.13 For instance, we consider

it as effective perceptive behaviour when the

sources of information are reduced to more

important ones. The player needs to perceive

the space-temporary information structure

from the environment to improve his actions.19

Therefore, it is not the quantity of information that will determine the success of the

action, but rather the quality and the speed

with which it is obtained.

An important aim of visual behaviour studies

in sport environments is to increase the spatial validity of these studies, while avoiding

the loss of experimental control. Also, the

perception and the action processes should be

understood as interdependent,7,8 since the

actions are determined by the previous perception process. The separated study of these

processes could create an artificial situation

which does not constitute a reliable measure

of the players´ experience in their sport environment.5 Therefore, the experiments of this

study were carried out in situations that

duplicate the real game environment, where

the players had not only to code and recover

information accurately, but also had to

respond under a pressured game situation.

In order to evaluate the visual search process,

the location of the visual fixations is assumed

to reflect the important cues used in decision-

making, whereas the number and duration of

the fixations are presumed to reflect the

information-processing demands placed on

the performer.19 That is, fixation characteristics are taken as representing the approach

used by the observer to extract specific information from the opponent.

The aims of our study were: a) to study the

visual and motor responses of tennis and

wheelchair tennis players in the return to

serve against biped and wheeler opponents;

b) to study the differences between experienced and novice wheelchair tennis players

Methods

An automated system is applied to study the

perceptive and motor behaviours of tennis

and wheelchair tennis players in a simulation

of return to serve situation, in real situation of

game (three-dimensional) as well as in videobased situation (two-dimensional), through

several technological subsystems.11

a) Visual behaviour. The ASL Eye Tracking

System SE5000 (Applied Sciences

LaboratoriesTM) allows us to obtain an

image with the point of gaze as seen by

the player.

b) Motor response and its precision. This system has been developed from a simulation

system for the training of open sport abilities, also applied in tennis.12 The players

must hit two surfaces located to their right

(forehand stroke) and to their left (backhand stroke) (Figure 1). We obtain values

for reaction time (RT), movement time

(MT) and reaction response (RR).

c) To measure and control the temporal

(speed) and spatial (precision) variability

of the serves.

d) To simulate the return to serve action by

means of video-based apparatus (twodimensional).

Three groups were studied: a) novices wheelchair tennis players (n=7 and less than 2 years

of experience); b) expert wheelchair tennis

players (n=5, included in top 10 Spanish

ranking and with international experience);

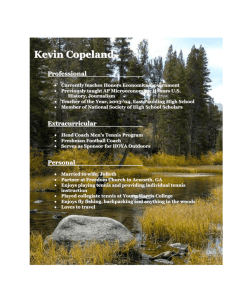

Figure 1 Parameters of the reaction response

(RT = reaction time, TM = movement time, RR = reaction response)

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 12

and c) young tennis players (n=6).

All participants were shown two series of 24

top-spin serves (one series in real game situation and the other one by video-projection),

performed by four right-handed players, two

in biped position and two seated in wheelchairs. The serves were performed to the

“cross” and to the “corner” of the serve square

in a pre-established random order.

Results

We analysed the number of visual fixations

(NF) and the duration of the fixations (TF)

on different body areas of the opponent, racket and ball for the following phases of the

serve: Phase A, as the player separates the

arms until the ball toss; Phase B, until the

head of the racket reaches the lowest point

before the hit; Phase C, until the hit of the

ball; and Phase D, until the ball hits the net

or it bounces on the court.

A repeated measures analysis of variance was

carried out (within-groups). Table 1 shows

the mean scores and the variables with significant differences among biped and wheeler

opponents, both in video-based and in court

situation. In the video-based situation, the

groups perform higher NF and TF on freearm, with higher values among the biped

opponents. On this location there were also

differences in phases A (NFA and TFA) and

B (NFB). In the court situation, only differences in NF and NFB are noted. About the

upper body, there are differences in the number of fixations and in the fixation time on

the racket-arm in the phase C. Finally, there

are many differences in fixation on the ball,

with higher mean values when the serve is

performed by a seated opponent, except in

the values of the phase A (when the hand of

the free-arm holds the ball). There are also

significant differences in the area where the

racket hits the ball (phase D), where the

players point their visual fixation before following the ball’s trajectory. The differences in

this area were obtained both in video-based

(F1,14 = 17.7; p<0.01) and in court situation

(F1,11 = 8.03; p<0.05).

With regard to motor response, another

repeated measures ANOVA analysis revealed

that players in both situations show better

reaction times and reaction responses with

serves directed toward a “forehand” movement (Table 2). For the serves directed

toward a “backhand” movement, there are

only significant differences in the reaction

time in the video-based situation (F1,15 = 5.97;

p<0.05). Another analysis of variance was

carried out between the experienced and

novice wheelchair tennis players. In the

video-based situation, against biped opponents, the experienced group showed higher

fixation time (5.89%) on the racket in phase

C (F1,9 = 5.8; p<0.05) than the novice ones

(1.22%). There are also differences in the fixation time on the upper body in phase A,

both in video-based (F1,9 = 14.31; p<0.01)

and in court situation (F1,9 = 6.6; p<0.05).

Finally, a Pearson correlation analysis between

visual behaviour and motor response data

Table 1 Repeated measures analysis of variance among seated and biped opponents in video-based and court situations for the visual behaviour (NF=number of visual fixation -n-; TF = time of visual fixation -%-)

Location

Measure

Phase

F

Sig.

M Seated

M Biped

Video-Based Situation (2D)

Free Arm

Racket Arm

Upper Body

Ball

NF

TF

NF

TF

NF

NF

TF

TF

NF

TF

NF

TF

NF

TF

NF

TF

–

–

A

A

B

C

C

–

B

B

C

–

A

C

D

D

14.81 (1,14)

8.66 (1,14)

15.18 (1,14)

5.92 (1,14)

8.9 (1,14)

6.88 (1,14)

4.67 (1,14)

5.21 (1,14)

14.02 (1,14)

6.68 (1,14)

7.04 (1,14)

7.12 (1,14)

5.69 (1,14)

6.6 (1,14)

13.63 (1,14)

15.21 (1,14)

0.002

0.011

0.002

0.029

0.010

0.020

0.048

0.039

0.002

0.022

0.019

0.018

0.032

0.022

0.002

0.002

1.27

15.99

1.22

39.27

0.27

0.38

22.48

27.02

0.57

17.55

0.12

44.51

0.11

75.71

3.38

58.36

1.89

23.37

1.80

51.03

0.47

0.57

33.7

32.03

0.88

27.56

0.26

39.99

0.22

63.08

2.66

50.24

–

B

–

–

A

A

D

4.903 (2,11)

10.229 (2,11)

8.895 (2,11)

5.004 (2,11)

27.110 (2,11)

5.359 (2,11)

8.963 (2,11)

0.049

0.008

0.012

0.047

0.000

0.041

0.012

1.41

0.18

22.25

52.34

0.12

1.58

67.61

1.86

0.39

26.02

48.28

0.25

2.83

55.25

Court Situation (3D)

Free Arm

Upper Body

Ball

NF

NF

TF

TF

NF

TF

TF

revealed a significant correlation between the

visual fixation on racket in phase C and the

movement time (cor.=-.971*) against seated

opponents. On the other hand, playing

against biped opponents, another correlation

was obtained between the fixation time on

the arm-racket and the reaction response

(cor.=-.977*).

Discussion and Conclusions

The study has been undertaken from a perception-action perspective, where action is

continuously being coupled to the perceptual

information presented.14,15

The higher visual fixation scores on the ball in

the serves performed by seated opponents

could be due to the fact that the player grabs

the rim of the wheelchair with the free arm,

in order to obtain stability during the serve.

The results obtained for the free-arm and the

ball in the phase A, with higher mean values

among biped servers, could support this

explanation. Nevertheless, it could also be

due to the lesser mobility experienced by the

players seated in the wheelchair, and the

need to acquire information from different

locations of the biped server. Therefore,

against seated opponents, the players perform

a longer pursuit of the ball’s trajectory and

they show lower fixations on the area where

the racket hits the ball. Furthermore, they

employ less time in starting the pursuit of the

ball’s trajectory because the serves of those

opponents was slower than those of biped

servers. This explanation is supported by

higher fixations on advanced areas of the

Table 2 Repeated measures analysis of variance

among seated and biped opponents in videobased and court situations for the motor

response (RT= reaction time; MT= movement

time; RR= reaction response -ms-)

Measure F

Sig.

M

Seated

M

Biped

0.005

0.721

0.077

261.52

156.49

408.93

210.48

151.95

366.51

0.019

0.125

0.008

316.75

147.91

464.41

276.61

139.15

412.93

Video-Based Situation (2D)

RT

MT

RR

10.70 (1,15)

0.13 (1,15)

3.60 (1,15)

Court Situation (3D)

RT

MT

RR

7.32 (1,12)

2.71 (1,12)

9.97 (1,12)

flight ball’s position for the serves performed

by seated players. On the other hand, higher

fixations were obtained in the posterior area

of the flight ball’s position for the serves performed by biped opponents. The higher values in the reaction response against biped

opponents could be due to a greater movement´ width, and it would offer important

cues to help in predicting trajectory before

the serve than it would be the case with

seated servers.13 Therefore, we should avoid

coaching situations where wheelchair tennis

players play against biped coaches/instructors,

since the information that they offer differs

from that which the player would obtain in

real game situation. Regarding the analysis of

the experience of the wheelchair tennis players, the higher fixations on the upper body

performed by the experienced players could

be due to their superior experience in the

sport, and that they are able to collect the

information they need to predict the ball’s

trajectory straightaway. Some authors consider that the motion of the racket before the

contact with the ball is one of the most reliable cues to predict the ball’s trajectory.6,12

The negative correlation between values of

the motor response and the fixation on the

arm-racket indicates that the experienced

players extract information that allows them

to obtain better values of motor response.

It seems that experienced players make better

use of the arm-racket information in order to

respond more quickly during play.17,18 The

implications of these results for learning

processes are important, since we they indicate that we should not only teach players to

guide the point of gaze to those important

cues, but also how they should interpret that

information.1,2 (90 minutes)

References

1. Abernethy B. The effects of age and

expertise upon perceptual skill development in a racquet sport. Res Q Exerc

Sport 1988;59(3):210-221.

2. Abernethy B. Visual search strategies and

decision–making in sport. Int J Sport

Psychol 1991;22:189-216.

3. Abernethy B, Wollstein J. Improving

anticipation in racquet sports. Sports

Coach 1989;12:15-18.

4. Arteaga M. Influencia del esfuerzo físico

MEDICINE

& SCIENCE

IN

TENNIS 13

anaeróbico en la percepción visual. Tesis

Doctoral. Universidad de Granada, 1999.

5. Chamberlain CJ, Coelho AJ. The perceptual side of action: Decision-making in

sport. In: JL Starkes and F.Allard (Eds.).

Cognitive issues in motor expertise.

Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 1993.

6. Farrow D, Abernethy B. Can anticipatory

skills be learned through implicit videobased perceptual training? J Sport Sci

2002;20:471-485.

7. McMorris T, Beazeley A. Performance of

experienced and inexperienced soccer

players on soccer specific tests of recall,

visual search and decision-making. J

Human Mov Stud 1997;33:1-13.

8. Mestre DR, Pailhous J. (1991). Expertise

in sports as a perceptivo-motor skills. Int J

Sport Psychol 1991;22:211-216.

9. Moreno FJ, Oña A. Analysis of a professional tennis player to determine anticipatory pre-cues in service. J Human Mov

Stud 1998;35:219-231.

10. Moreno FJ, Oña A, Martínez M.

Computerized simulation as a means of

improving anticipation strategies and

training in the use of the return in tennis.

J Human Mov Stud 2002;42:31-41.

11. Moreno FJ, Reina R, Luis V, Damas JS,

Sabido R. Desarrollo de un sistema tecnológico para el registro del comportamiento de jugadores de tenis y tenis en

silla de ruedas en situaciones de respuesta

de reacción. Motricidad. Eur J Human

Mov 2003;10:165-190.

12. Moreno FJ, Reina R, Sanz D, Ávila F. Las

estrategias de búsqueda visual de

jugadores expertos de tenis en silla de

ruedas. Revista de Psicología del

Deporte, 2002;11(2):197-208.

13. Reina R. Estudio de la influencia de la

lateralidad y la posición del oponente en

el servicio de tenis sobre el proceso perceptivo de tenistas en silla de ruedas.

Tesis de Máster (European Master

Degree in Adapted Physical Activity).

Katholieke Universiteit Leuven e Institut

Nacional d´Educació Física Lleida, 2002.

14. Savelsbergh GJP, Van der Kamp J.

(2000). Information in learning to coordinate and control movements: Is there a

need for specificity of practice? Int J

Sport Psychol 2000;31:476-484.

15. Savelsbergh GJP, Williams AM, Van der

Kamp J, Ward P. Visual search, anticipation and expertise in soccer goalkeepers.

J Sport Sci 2002;20:279-287.

16. Singer RN, Williams AM, Frehlich SG,

Janelle CM, Radlo SJ, Barba DA,

Bouchard LJ. New frontiers in visual

search: An exploratory study in live

tennis situations. Res Q Exerc Sport

1998;69(3):290-296.

17. Starkes JL, Allard F. Cognitive issues in

motor control. Amsterdam: North

Holland, 1993.

18. Tenenbaum G. The development of

expertise in sport: Nature and nurture.

Int J Sport Psychol 1999;30:113-304.

19. Williams AM, Davids K, Williams JG.

Visual perception and action in sport.

London: E & FN Spon, 1999.

20. Williams AM, Davids K, Burwitz L,

Williams JG. Perception and action in

sport. J Human Mov Stud 1992;22:

147-205.

21. Williams AM, Davids K, Burwitz L,

Williams JG. Visual search strategies in

experienced and inexperienced soccer

players. Res Q Exerc Sport 1994;65(2):

127-135.

Clinical Practice Guidelines in The Netherlands

THE ROYAL DUTCH SOCIETY FOR PHYSICAL THERAPY (KNGF)

A prospect for continuous quality improvement in physical therapy

ROELOF BOEKEMA PT, HANZEHOGESCHOOL GRONINGEN, DEPT. OF PHYSIOTHERAPY,

VAN SWIETENLAAN 1, 9728 NX GRONINGEN, THE NETHERLANDS. TEL +31 50 595 3763. E-MAIL: R.D.BOEKEMA@PL.HANZE.NL

s a result of international collaboration

in guideline development, The Royal

Dutch Society for Physical Therapy has

translated nine evidence-based clinical

practice guidelines into English to make

the guidelines accessible at an international level. The clinical practice guidelines in

Physical Therapy make it possible for

Physical Therapists to use the guidelines as

a reference for treating their patients.

A

In evidence based clinical practise guidelines, best practise in Physical Therapy

diagnosis and treatment is described, based

on available scientific evidence and experience from clinical practice. Clinical practice guidelines are ‘systematically developed statements to assist both practitioner

and patient when making decisions about

appropriate health care for specific clinical

circumstances’1.

Their purpose is ‘to make explicit recommendations with a definite intent to influence what clinicians do’2. There is some

proof that evidence based guidelines are

instruments to provide insight, both in

quantity as in quality, in the health care

provided. It has been suggested that guidelines are adequate management instru-

ments for continuous quality improvement, quality assurance and continuing

education3.

Currently nine evidence-based guidelines

have been developed and can be downloaded

from our website at:

www.fysionet.nl/index.hmtl?menuIO=62

• Acute ankle sprain

• Chronic ankle sprain