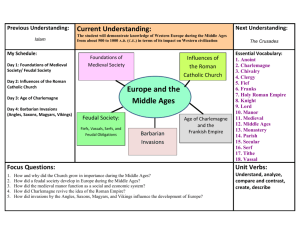

European Middle Ages,

advertisement

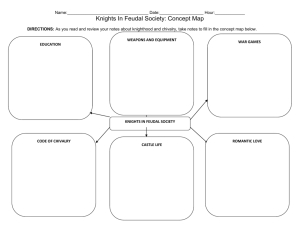

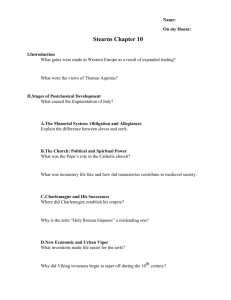

European Middle Ages, 500-1200 Previewing Main Ideas EMPIRE BUILDING In western Europe, the Roman Empire had broken into many small kingdoms. During the Middle Ages, Charlemagne and Otto the Great tried to revive the idea of empire. Both allied with the Church. Geography Study the maps. What were the six major kingdoms in western Europe about A.D. 500? POWER AND AUTHORITY Weak rulers and the decline of central authority led to a feudal system in which local lords with large estates assumed power. This led to struggles over power with the Church. Geography Study the time line and the map. The ruler of what kingdom was crowned emperor by Pope Leo III? RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS During the Middle Ages, the Church was a unifying force. It shaped people’s beliefs and guided their daily lives. Most Europeans at this time shared a common bond of faith. Geography Find Rome, the seat of the Roman Catholic Church, on the map. In what kingdom was it located after the fall of the Roman Empire in A.D. 476? INTERNET RESOURCES • Interactive Maps • Interactive Visuals • Interactive Primary Sources 350 Go to classzone.com for: • Research Links • Maps • Internet Activities • Test Practice • Primary Sources • Current Events • Chapter Quiz 351 What freedoms would you give up for protection? You are living in the countryside of western Europe during the 1100s. Like about 90 percent of the population, you are a peasant working the land. Your family’s hut is located in a small village on your lord’s estate. The lord provides all your basic needs, including housing, food, and protection. Especially important is his protection from invaders who repeatedly strike Europe. 1 For safety, peasants retreat behind the castle walls during attacks. 2 Peasants owe their lord two or three days’ labor every week farming his land. 3 This peasant feels that the right to stay on his lord’s land is more important than his freedom to leave. 4 Peasants cannot marry without their lord’s consent. EXAM I N I NG the ISSU ES • What is secure about your world? • How is your life limited? As a class, discuss these questions. In your discussion, think about other people who have limited power over their lives. As you read about the lot of European peasants in this chapter, see how their living arrangements determine their role in society and shape their beliefs. 352 Chapter 13 1 Charlemagne Unites Germanic Kingdoms MAIN IDEA EMPIRE BUILDING Many Germanic kingdoms that succeeded the Roman Empire were reunited under Charlemagne’s empire. WHY IT MATTERS NOW Charlemagne spread Christian civilization through Northern Europe, where it had a permanent impact. TERMS & NAMES • • • • Middle Ages Franks monastery secular • Carolingian Dynasty • Charlemagne SETTING THE STAGE The gradual decline of the Roman Empire ushered in an era of European history called the Middle Ages, or the medieval period. It spanned the years from about 500 to 1500. During these centuries, a new society slowly emerged. It had roots in: (1) the classical heritage of Rome, (2) the beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church, and (3) the customs of various Germanic tribes. Invasions of Western Europe TAKING NOTES In the fifth century, Germanic invaders overran the western half of the Roman Empire (see map on page 351). Repeated invasions and constant warfare caused a series of changes that altered the economy, government, and culture: • Disruption of Trade Merchants faced invasions from both land and sea. Their businesses collapsed. The breakdown of trade destroyed Europe’s cities as economic centers. Money became scarce. • Downfall of Cities With the fall of the Roman Empire, cities were abandoned as centers of administration. • Population Shifts As Roman centers of trade and government collapsed, nobles retreated to the rural areas. Roman cities were left without strong leadership. Other city dwellers also fled to the countryside, where they grew their own food. The population of western Europe became mostly rural. Following Chronological Order Note important events in the unification of the Germanic kingdoms. 500 1200 The Decline of Learning The Germanic invaders who stormed Rome could not read or write. Among Romans themselves, the level of learning sank sharply as more and more families left for rural areas. Few people except priests and other church officials were literate. Knowledge of Greek, long important in Roman culture, was almost lost. Few people could read Greek works of literature, science, and philosophy. The Germanic tribes, though, had a rich oral tradition of songs and legends. But they had no written language. Loss of a Common Language As German-speaking peoples mixed with the Roman population, Latin changed. While it was still an official language, it was no longer understood. Different dialects developed as new words and phrases became part of everyday speech. By the 800s, French, Spanish, and other Roman-based languages had evolved from Latin. The development of various languages mirrored the continued breakup of a once-unified empire. European Middle Ages 353 Germanic Kingdoms Emerge In the years of upheaval between 400 and 600, small Germanic kingdoms replaced Roman provinces. The borders of those kingdoms changed constantly with the fortunes of war. But the Church as an institution survived the fall of the Roman Empire. During this time of political chaos, the Church provided order and security. The Concept of Government Changes Along with shifting boundaries, the entire concept of government changed. Loyalty to public government and written law had unified Roman society. Family ties and personal loyalty, rather than citizenship in a public state, held Germanic society together. Unlike Romans, Germanic peoples lived in small communities that were governed by unwritten rules and traditions. Every Germanic chief led a band of warriors who had pledged their loyalty to him. In peacetime, these followers lived in their lord’s hall. He gave them food, weapons, and treasure. In battle, warriors fought to the death at their lord’s side. They considered it a disgrace to outlive him. But Germanic warriors felt no obligation to obey a king they did not even know. Nor would they obey an official sent to collect taxes or administer justice in the name of an emperor they had never met. The Germanic stress on personal ties made it impossible to establish orderly government for large territories. ▼ Illuminated manuscripts, such as the one below, were usually the work of monks. Clovis Rules the Franks In the Roman province of Gaul (mainly what is now France and Switzerland), a Germanic people called the Franks held power. Their leader was Clovis (KLOH•vihs). He would bring Christianity to the region. According to legend, his wife, Clothilde, had urged him to convert to her faith, Christianity. In 496, Clovis led his warriors against another Germanic army. Fearing defeat, he appealed to the Christian God. “For I have called on my gods,” he prayed, “but I find they are far from my aid. . . . Now I call on Thee. I long to believe in Thee. Only, please deliver me from my enemies.” The tide of the battle shifted and the Franks won. Afterward, Clovis and 3,000 of his warriors asked a bishop to baptize them. The Church in Rome welcomed Clovis’s conversion and supported his military campaigns against other Germanic peoples. By 511, Clovis had united the Franks into one kingdom. The strategic alliance between Clovis’s Frankish kingdom and the Church marked the start of a partnership between two powerful forces. Germans Adopt Christianity Politics played a key role in spreading Christianity. By 600, the Church, with the help of Frankish rulers, had converted many Germanic peoples. These new converts had settled in Rome’s former lands. Missionaries also spread Christianity. These religious travelers often risked their lives to bring religious beliefs to other lands. During the 300s and 400s, they worked among the Germanic and Celtic groups that bordered the Roman Empire. In southern Europe, the fear of coastal attacks by Muslims also spurred many people to become Christians in the 600s. Monasteries, Convents, and Manuscripts To adapt to rural conditions, the Church built religious communities called monasteries. There, Christian men called monks gave up their private possessions and devoted their lives to serving God. Women who followed this way of life were called nuns and lived in convents. 354 Chapter 13 Benedict 480?–543 Scholastica 480?–543 At 15, Benedict left school and hiked up to the Sabine Hills, where he lived in a cave as a hermit. After learning about Benedict’s deep religious conviction, a group of monks persuaded him to lead their monastery. Benedict declared: Scholastica is thought to be the twin sister of Benedict. She was born into a wealthy Italian family in the late Roman Empire. Little is known of her early life, except that she and Benedict were inseparable. Like her brother, Scholastica devoted her life to the Church. She is thought to have been the abbess of a convent near the monastery founded by Benedict and is considered the first nun of the Benedictine order. She was a strong influence on her brother as he developed rules that guide Benedictine monasteries to this day. They died in the same year and are buried in one grave. We must prepare our hearts and bodies for combat under holy obedience to the divine commandments. . . . We are therefore going to establish a school in which one may learn the service of the Lord. In his book describing the rules for monastic life, Benedict emphasized a balance between work and study. Such guidelines turned monasteries into centers of stability and learning. Making Inferences What role did monasteries play during this time of chaos? RESEARCH LINKS For more on Benedict and Scholastica, go to classzone.com Around 520, an Italian monk named Benedict began writing a book describing a strict yet practical set of rules for monasteries. Benedict’s sister, Scholastica (skuh•LAS•tik•uh), headed a convent and adapted the same rules for women. These guidelines became a model for many other religious communities in western Europe. Monks and nuns devoted their lives to prayer and good works. Monasteries also became Europe’s best-educated communities. Monks opened schools, maintained libraries, and copied books. In 731, the Venerable Bede, an English monk, wrote a history of England. Scholars still consider it the best historical work of the early Middle Ages. In the 600s and 700s, monks made beautiful copies of religious writings, decorated with ornate letters and brilliant pictures. These illuminated manuscripts preserved at least part of Rome’s intellectual heritage. Papal Power Expands Under Gregory I In 590, Gregory I, also called Gregory the Great, became pope. As head of the Church in Rome, Gregory broadened the authority of the papacy, or pope’s office, beyond its spiritual role. Under Gregory, the papacy also became a secular, or worldly, power involved in politics. The pope’s palace was the center of Roman government. Gregory used church revenues to raise armies, repair roads, and help the poor. He also negotiated peace treaties with invaders such as the Lombards. According to Gregory, the region from Italy to England and from Spain to Germany fell under his responsibility. Gregory strengthened the vision of Christendom. It was a spiritual kingdom fanning out from Rome to the most distant churches. This idea of a churchly kingdom, ruled by a pope, would be a central theme of the Middle Ages. Meanwhile, secular rulers expanded their political kingdoms. An Empire Evolves After the Roman Empire dissolved, small kingdoms sprang up all over Europe. For example, England splintered into seven tiny kingdoms. Some of them were no European Middle Ages 355 50°N 0° North Sea 16°E Frankish Kingdom before Charlemagne, 768 Areas conquered by Charlemagne, 814 Papal States Division by Treaty of Verdun, 843 8°E Charlemagne‘s Empire, 768–843 0 250 Miles 0 500 Kilometers Elb eR . ENGLAND larger than the state of Connecticut. The Franks controlled the largest and strongest of Europe’s kingdoms, the area that was formerly the Roman province of Gaul. When the Franks’ first Christian king, Clovis, died in 511, he had extended Frankish rule over most of what is now France. Rh i ne Charles Martel Emerges By 700, an official known as the major domo, or EAST Paris mayor of the palace, had become the FRANKISH KINGDOM Tours most powerful person in the Frankish (Louis Danube R. the German) kingdom. Officially, he had charge of WEST ATLANTIC FRANKISH the royal household and estates. OCEAN KINGDOM CENTRAL Unofficially, he led armies and made (Charles KINGDOM Pavia the Bald) policy. In effect, he ruled the kingdom. (Lothair ) The mayor of the palace in 719, 42°N Charles Martel (Charles the Hammer), PAPAL Corsica STATES held more power than the king. Charles SPAIN Rome Mediterranean Martel extended the Franks’ reign to the Sea north, south, and east. He also defeated Muslim raiders from Spain at the Battle GEOGRAPHY SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Maps of Tours in 732. This battle was highly 1. Region By 814, what was the extent of Charlemagne’s significant for Christian Europeans. If empire (north to south, east to west)? the Muslims had won, western Europe 2. Region Based on the map, why did the Treaty of Verdun might have become part of the Muslim signal the decline of Charlemagne’s empire? Empire. Charles Martel’s victory at Tours made him a Christian hero. At his death, Charles Martel passed on his power to his son, Pepin the Short. Pepin wanted to be king. He shrewdly cooperated with the pope. On behalf of the Church, Pepin agreed to fight the Lombards, who had invaded central Italy and threatened Rome. In exchange, the pope anointed Pepin “king by the grace of God.” Thus began the Carolingian (KAR•uh•LIHN•juhn) Dynasty, the family that would rule the Franks from 751 to 987. Aachen R. SLAVIC STATES ro Eb R. Charlemagne Becomes Emperor Pepin the Short died in 768. He left a greatly strengthened Frankish kingdom to his two sons, Carloman and Charles. After Carloman’s death in 771, Charles, who was known as Charlemagne (SHAHR•luh•MAYN), or Charles the Great, ruled the kingdom. An imposing figure, he stood six feet four inches tall. His admiring secretary, a monk named Einhard, described Charlemagne’s achievements: PRIMARY SOURCE [Charlemagne] was the most potent prince with the greatest skill and success in different countries during the forty-seven years of his reign. Great and powerful as was the realm of Franks, Karl [Charlemagne] received from his father Pippin, he nevertheless so splendidly enlarged it . . . that he almost doubled it. EINHARD, Life of Charlemagne Charlemagne Extends Frankish Rule Charlemagne built an empire greater than any known since ancient Rome. Each summer he led his armies against enemies that surrounded his kingdom. He fought Muslims in Spain and tribes from other 356 Chapter 13 Germanic kingdoms. He conquered new lands to both the south and the east. Through these conquests, Charlemagne spread Christianity. He reunited western Europe for the first time since the Roman Empire. By 800, Charlemagne’s empire was larger than the Byzantine Empire. He had become the most powerful king in western Europe. In 800, Charlemagne traveled to Rome to crush an unruly mob that had attacked the pope. In gratitude, Pope Leo III crowned him emperor. The coronation was historic. A pope had claimed the political right to confer the title “Roman Emperor” on a European king. This event signaled the joining of Germanic power, the Church, and the heritage of the Roman Empire. Charlemagne Leads a Revival Charlemagne strengthened his royal power by limiting the authority of the nobles. To govern his empire, he sent out royal agents. They made sure that the powerful landholders, called counts, governed their counties justly. Charlemagne regularly visited every part of his kingdom. He also kept a close watch on the management of his huge estates—the source of Carolingian wealth and power. One of his greatest accomplishments was the encouragement of learning. He surrounded himself with English, German, Italian, and Spanish scholars. For his many sons and daughters and other children at the court, Charlemagne opened a palace school. He also ordered monasteries to open schools to train future monks and priests. Drawing Conclusions What were Charlemagne’s most notable achievements? SECTION Charlemagne’s Heirs A year before Charlemagne died in 814, he crowned his only surviving son, Louis the Pious, as emperor. Louis was a devoutly religious man but an ineffective ruler. He left three sons: Lothair (loh•THAIR), Charles the Bald, and Louis the German. They fought one another for control of the Empire. In 843, the brothers signed the Treaty of Verdun, dividing the empire into three kingdoms. As a result, Carolingian kings lost power and central authority broke down. The lack of strong rulers led to a new system of governing and landholding—feudalism. 1 ▲ Emperor Charlemagne ASSESSMENT TERMS & NAMES 1. For each term or name, write a sentence explaining its significance. • Middle Ages • Franks • monastery • secular • Carolingian Dynasty • Charlemagne USING YOUR NOTES MAIN IDEAS CRITICAL THINKING & WRITING 2. What was the most important 3. What were three roots of 6. DRAWING CONCLUSIONS How was the relationship event in the unification of the Germanic kingdoms? Why? medieval culture in western Europe? 4. What are three ways that civilization in western Europe declined after the Roman Empire fell? 500 1200 5. What was the most important achievement of Pope Gregory I? between a Frankish king and the pope beneficial to both? 7. RECOGNIZING EFFECTS Why was Charles Martel’s victory at the Battle of Tours so important for Christianity? 8. EVALUATING What was Charlemagne’s greatest achievement? Give reasons for your answer. 9. WRITING ACTIVITY EMPIRE BUILDING How does Charlemagne’s empire in medieval Europe compare with the Roman Empire? Support your opinions in a threeparagraph expository essay. INTERNET ACTIVITY Use the Internet to locate a medieval monastery that remains today in western Europe. Write a two-paragraph history of the monastery and include an illustration. INTERNET KEYWORD Medieval monasteries European Middle Ages 357 2 Feudalism in Europe MAIN IDEA POWER AND AUTHORITY Feudalism, a political and economic system based on land-holding and protective alliances, emerges in Europe. WHY IT MATTERS NOW The rights and duties of feudal relationships helped shape today’s forms of representative government. TERMS & NAMES • • • • lord fief vassal knight • serf • manor • tithe SETTING THE STAGE After the Treaty of Verdun, Charlemagne’s three feud- ing grandsons broke up the kingdom even further. Part of this territory also became a battleground as new waves of invaders attacked Europe. The political turmoil and constant warfare led to the rise of European feudalism, which, as you read in Chapter 2, is a political and economic system based on land ownership and personal loyalty. TAKING NOTES Analyzing Causes and Recognizing Effects Use a web diagram to show the causes and effects of feudalism. Cause Cause Feudalism Effect Effect 358 Chapter 13 Invaders Attack Western Europe From about 800 to 1000, invasions destroyed the Carolingian Empire. Muslim invaders from the south seized Sicily and raided Italy. In 846, they sacked Rome. Magyar invaders struck from the east. Like the earlier Huns and Avars, they terrorized Germany and Italy. And from the north came the fearsome Vikings. The Vikings Invade from the North The Vikings set sail from Scandinavia (SKAN•duh•NAY•vee•uh), a wintry, wooded region in Northern Europe. (The region is now the countries of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.) The Vikings, also called Northmen or Norsemen, were a Germanic people. They worshiped warlike gods and took pride in nicknames like Eric Bloodaxe and Thorfinn Skullsplitter. The Vikings carried out their raids with terrifying speed. Clutching swords and heavy wooden shields, these helmeted seafarers beached their ships, struck quickly, and then moved out to sea again. They were gone before locals could mount a defense. Viking warships were awe-inspiring. The largest of these long ships held 300 warriors, who took turns rowing the ship’s 72 oars. The prow of each ship swept grandly upward, often ending with the carved head of a sea monster. A ship might weigh 20 tons when fully loaded. Yet, it could sail in a mere three feet of water. Rowing up shallow creeks, the Vikings looted inland villages and monasteries. ▼ A sketch of a Viking longboat Invasions in Europe, 700–1000 0 To Iceland 58° N 500 Miles 1,000 Kilometers 24° W 0 SCANDINAVIA V o l g a R. Se IRELAND 50° W. D v a North Sea N R. r R. iepe Dn Ba ENGLAND in a ltic Tours 42° N PA Genoa Corsica TH Ca IA N M Pisa Black Rome BYZANTINE EMPIRE 48°E 32°E 24°E Sicily 16°E N 8°E n Viking invasion routes Viking areas Muslim invasion routes Muslim areas Magyar invasion routes Magyar areas Constantinople 34° 0° ia Sea Sardinia 8°W sp a ES CAR Se NE R. . CALIPHATE OF CÓRDOVA RE a n ube TS PY R. ne ALPS FRANCE Vol ga R. Kiev B Rhône R urgu nd . y Rh ine Rh land i Paris Aachen e R. D ATLAN TIC O CEAN 16° ien S W London R US S IA GEOGRAPHY SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Maps 1. Location What lands did the Vikings raid? 2. Movement Why were the Viking, Magyar, and Muslim invasions so threatening to Europe? The Vikings were not only warriors but also traders, farmers, and explorers. They ventured far beyond western Europe. Vikings journeyed down rivers into the heart of Russia, to Constantinople, and even across the icy waters of the North Atlantic. A Viking explorer named Leif (leef) Ericson reached North America around 1000, almost 500 years before Columbus. About the same time, the Viking reign of terror in Europe faded away. As Vikings gradually accepted Christianity, they stopped raiding monasteries. Also, a warming trend in Europe’s climate made farming easier in Scandinavia. As a result, fewer Scandinavians adopted the seafaring life of Viking warriors. Magyars and Muslims Attack from the East and South As Viking invasions declined, Europe became the target of new assaults. The Magyars, a group of nomadic people, attacked from the east, from what is now Hungary. Superb horsemen, the Magyars swept across the plains of the Danube River and invaded western Europe in the late 800s. They attacked isolated villages and monasteries. They overran northern Italy and reached as far west as the Rhineland and Burgundy. The Magyars did not settle conquered land. Instead, they took captives to sell as slaves. The Muslims struck from the south. They began their encroachments from their strongholds in North Africa, invading through what are now Italy and Spain. In the 600s and 700s, the Muslim plan was to conquer and settle in Europe. By the 800s and 900s, their goal was also to plunder. Because the Muslims were expert seafarers, they were able to attack settlements on the Atlantic and Mediterranean coasts. They also struck as far inland as Switzerland. The invasions by Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims caused widespread disorder and suffering. Most western Europeans lived in constant danger. Kings could not European Middle Ages 359 effectively defend their lands from invasion. As a result, people no longer looked to a central ruler for security. Instead, many turned to local rulers who had their own armies. Any leader who could fight the invaders gained followers and political strength. A New Social Order: Feudalism In 911, two former enemies faced each other in a peace ceremony. Rollo was the head of a Viking army. Rollo and his men had been plundering the rich Seine (sayn) River valley for years. Charles the Simple was the king of France but held little power. Charles granted the Viking leader a huge piece of French territory. It became known as Northmen’s land, or Normandy. In return, Rollo swore a pledge of loyalty to the king. Recognizing Effects What was the impact of Viking, Magyar, and Muslim invasions on medieval Europe? Feudalism Structures Society The worst years of the invaders’ attacks spanned roughly 850 to 950. During this time, rulers and warriors like Charles and Rollo made similar agreements in many parts of Europe. The system of governing and landholding, called feudalism, had emerged in Europe. A similar feudal system existed in China under the Zhou Dynasty, which ruled from around the 11th century B.C. until 256 B.C. Feudalism in Japan began in A.D. 1192 and ended in the 19th century. The feudal system was based on rights and obligations. In exchange for military protection and other services, a lord, or landowner, granted land called a fief.The person receiving a fief was called a vassal. Charles the Simple, the lord, and Rollo, the vassal, showed how this two-sided bargain worked. Feudalism depended on the control of land. The Feudal Pyramid The structure of feudal society was much like a pyramid. At the peak reigned the king. Next came the most powerful vassals—wealthy landowners such as nobles and bishops. Serving beneath these vassals were knights. Knights were mounted horsemen who pledged to defend their lords’ lands in exchange for fiefs. At the base of the pyramid were landless peasants who toiled in the fields. (See Analyzing Key Concepts on next page.) Social Classes Are Well Defined In the feudal system, status determined a per- son’s prestige and power. Medieval writers classified people into three groups: those who fought (nobles and knights), those who prayed (men and women of the Church), and those who worked (the peasants). Social class was usually inherited. In Europe in the Middle Ages, the vast majority of people were peasants. Most peasants were serfs. Serfs were people who could not lawfully leave the place where they were born. Though bound to the land, serfs were not slaves. Their lords could not sell or buy them. But what their labor produced belonged to the lord. Manors: The Economic Side of Feudalism The manor was the lord’s estate. During the Middle Ages, the manor system was the basic economic arrangement. The manor system rested on a set of rights and obligations between a lord and his serfs. The lord provided the serfs with housing, farmland, and protection from bandits. In return, serfs tended the lord’s lands, cared for his animals, and performed other tasks to maintain the estate. Peasant women shared in the farm work with their husbands. All peasants, whether free or serf, owed the lord certain duties. These included at least a few days of labor each week and a certain portion of their grain. A Self-Contained World Peasants rarely traveled more than 25 miles from their own manor. By standing in the center of a plowed field, they could see their entire world at a glance. A manor usually covered only a few square miles of land. It 360 Chapter 13 Vocabulary Status is social ranking. Feudalism FEUDAL FACTS AND FIGURES Feudalism was a political system in which nobles were granted the use of land that legally belonged to the king. In return, the nobles agreed to give their loyalty and military services to the king. Feudalism developed not only in Europe but also in countries like Japan. European Feudalism • In the 14th century, before the bubonic plague struck, the population of France was probably between 10 and 21 million people. • In feudal times, the building of King a cathedral took between 50 to 150 years. • In feudal times, dukedoms Church Official were large estates ruled by a duke. In 1216, the Duke of Anjou had 34 knights, the Duke of Brittany had 36 knights, and the Count of Flanders had 47 knights. Noble Knights • In the 14th century, the nobility Knights in France made up about 1 percent of the population. • The word feudalism comes from the Latin word feudum, meaning fief. Peasants Peasants Emperor comes from the words dai, meaning “large,” and myo (shorten from myoden), meaning “name-land” or “private land.” * SOURCES: A Distant Mirror by Barbara Tuchman; Encyclopaedia Britannica Japanese Feudalism Daimyo • The Japanese word daimyo Daimyo Samurai Samurai Artisans Peasants 1. Comparing What are the similarities between feudalism in Europe and feudalism in Japan? See Skillbuilder Handbook, Page R7. Merchants RESEARCH LINKS For more on feudalism, go to classzone.com 2. Forming and Supporting Opinions Today, does the United States have a system of social classes? Support your answer with evidence. 361 The Medieval Manor The medieval manor varied in size. The illustration to the right is a plan of a typical English manor. 1 Manor House The dwelling place of the lord and his family and their servants 2 Village Church Site of both religious services and public meetings 3 Peasant Cottages Where the peasants lived 4 Lord’s Demesne Fields owned by the lord and worked by the peasants 5 Peasant Crofts Gardens that belonged to the peasants 6 Mill Water-powered mill for grinding grain 7 Common Pasture Common area for grazing animals 8 Woodland Forests provided wood for fuel. typically consisted of the lord’s manor house, a church, and workshops. Generally, 15 to 30 families lived in the village on a manor. Fields, pastures, and woodlands surrounded the village. Sometimes a stream wound through the manor. Streams and ponds provided fish, which served as an important source of food. The mill for grinding the grain was often located on the stream. The manor was largely a self-sufficient community. The serfs and peasants raised or produced nearly everything that they and their lord needed for daily life— crops, milk and cheese, fuel, cloth, leather goods, and lumber. The only outside purchases were salt, iron, and a few unusual objects such as millstones. These were huge stones used to grind flour. Crops grown on the manor usually included grains, such as wheat, rye, barley, and oats, and vegetables, such as peas, beans, onions, and beets. The Harshness of Manor Life For the privilege of living on the lord’s land, peasants paid a high price. They paid a tax on all grain ground in the lord’s mill. Any attempt to avoid taxes by baking bread elsewhere was treated as a crime. Peasants also paid a tax on marriage. Weddings could take place only with the lord’s 362 Chapter 13 Analyzing Causes How might the decline of trade during the early Middle Ages have contributed to the self-sufficiency of the manor system? consent. After all these payments to the lord, peasant families owed the village priest a tithe, or church tax. A tithe represented one-tenth of their income. Serfs lived in crowded cottages, close to their neighbors. The cottages had only one or two rooms. If there were two rooms, the main room was used for cooking, eating, and household activities. The second was the family bedroom. Peasants warmed their dirt-floor houses by bringing pigs inside. At night, the family huddled on a pile of straw that often crawled with insects. Peasants’ simple diet consisted mainly of vegetables, coarse brown bread, grain, cheese, and soup. Piers Plowman, written by William Langland in 1362, reveals the hard life of English peasants: Analyzing Primary Sources What problems did peasant families face? PRIMARY SOURCE What by spinning they save, they spend it in house-hire, Both in milk and in meal to make a mess of porridge, To cheer up their children who chafe for their food, And they themselves suffer surely much hunger And woe in the winter, with waking at nights And rising to rock an oft restless cradle. WILLIAM LANGLAND, Piers Plowman For most serfs, both men and women, life was work and more work. Their days revolved around raising crops and livestock and taking care of home and family. As soon as children were old enough, they were put to work in the fields or in the home. Many children did not survive to adulthood. Illness and malnutrition were constant afflictions for medieval peasants. Average life expectancy was about 35 years. And during that short lifetime, most peasants never traveled more than 25 miles from their homes. Yet, despite the hardships they endured, serfs accepted their lot in life as part of the Church’s teachings. They, like most Christians during medieval times, believed that God determined a person’s place in society. 2 SECTION This 14th century drawing shows two men flailing corn. ASSESSMENT TERMS & NAMES 1. For each term or name, write a sentence explaining its significance. • lord • fief • vassal • knight • serf • manor • tithe USING YOUR NOTES MAIN IDEAS CRITICAL THINKING & WRITING 2. What is the main reason 3. What groups invaded Europe in the 800s? 6. COMPARING How were the Vikings different from earlier 4. What obligations did a peasant 7. MAKING INFERENCES How was a manor largely self- feudalism developed? Explain. have to the lord of the manor? Cause Cause 5. What were the three social classes of the feudal system? Feudalism Germanic groups that invaded Europe? sufficient both militarily and economically during the early Middle Ages? 8. DRAWING CONCLUSIONS What benefits do you think a medieval manor provided to the serfs who lived there? 9. WRITING ACTIVITY POWER AND AUTHORITY Draw up a Effect Effect contract between a lord and a vassal, such as a knight, or between the lord of a manor and a serf. Include the responsibilities, obligations, and rights of each party. CONNECT TO TODAY WRITING A NEWS ARTICLE Research modern marauders, who, like the Vikings of history, are involved in piracy on the seas. Write a brief news article describing their activities. European Middle Ages 363 3 The Age of Chivalry MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS The code of chivalry has shaped modern ideas of romance in Western cultures. The code of chivalry for knights glorified both combat and romantic love. TERMS & NAMES • chivalry • tournament • troubadour SETTING THE STAGE During the Middle Ages, nobles constantly fought one another. Their feuding kept Europe in a fragmented state for centuries. Through warfare, feudal lords defended their estates, seized new territories, and increased their wealth. Lords and their armies lived in a violent society that prized combat skills. By the 1100s, though, a code of behavior began to arise. High ideals guided warriors’ actions and glorified their roles. TAKING NOTES Summarizing Identify the ideas associated with chivalry. Knights: Warriors on Horseback Soldiers mounted on horseback became valuable in combat during the reign of Charlemagne’s grandfather, Charles Martel, in the 700s. Charles Martel had observed that the Muslim cavalry often turned the tide of battles. As a result, he organized Frankish troops of armored horsemen, or knights. The Technology of Warfare Changes Leather saddles and stirrups changed the Chivalry way warfare was conducted in Europe during the 700s. Both had been developed in Asia around 200 B.C. The saddle kept a warrior firmly seated on a moving horse. Stirrups enabled him to ride and handle heavier weapons. Without stirrups to brace him, a charging warrior was likely to topple off his own horse. Frankish knights, galloping full tilt, could knock over enemy foot soldiers and riders on horseback. Gradually, mounted knights became the most important part of an army. Their warhorses played a key military role. The Warrior’s Role in Feudal Society By the 11th century, western Europe was a battleground of warring nobles vying for power. To defend their territories, feudal lords raised private armies of knights. In exchange for military service, 2 inches ▲ These twoinch iron spikes, called caltrops, were strewn on a battlefield to maim warhorses or enemy foot soldiers. 0 364 Chapter 13 feudal lords used their most abundant resource—land. They rewarded knights, their most skilled warriors, with fiefs from their sprawling estates. Wealth from these fiefs allowed knights to devote their lives to war. Knights could afford to pay for costly weapons, armor, and warhorses. As the lord’s vassal, a knight’s main obligation was to serve in battle. From his knights, a lord typically demanded about 40 days of combat a year. Knights’ pastimes also often revolved around training for war. Wrestling and hunting helped them gain strength and practice the skills they would need on the battlefield. Knighthood and the Code of Chivalry Knights were expected to display courage in battle and loyalty to their lord. By the 1100s, the code of chivalry (SHIHV•uhl•ree), a complex set of ideals, demanded that a knight fight bravely in defense of three masters. He devoted himself to his earthly feudal lord, his heavenly Lord, and his chosen lady. The chivalrous knight also protected the weak and the poor. The ideal knight was loyal, brave, and courteous. Most knights, though, failed to meet all of these high standards. For example, they treated the lower classes brutally. A Knight’s Training Sons of nobles began training for knighthood at an early age and learned the code of chivalry. At age 7, a boy would be sent off to the castle of another lord. As a page, he waited on his hosts and began to practice fighting skills. At around age 14, the page reached the rank of squire. A squire acted as a servant to a knight. At around age 21, a squire became a full-fledged knight. Chivalry The Italian painter Paolo Uccello captures the spirit of the age of chivalry in this painting, St. George and the Dragon (c. 1455–1460). According to myth, St. George rescues a captive princess by killing her captor, a dragon. • The Knight St. George, mounted on a horse and dressed in armor, uses his lance to attack the dragon. • The Dragon The fiercelooking dragon represents evil. • The Princess The princess remains out of the action as her knight fights the dragon on her behalf. SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Visual Sources In what way does this painting show the knight’s code of chivalry? European Middle Ages 365 Castles and Siege Weapons Attacking armies carefully planned how to capture a castle. Engineers would inspect the castle walls for weak points in the stone. Then, enemy soldiers would try to ram the walls, causing them to collapse. At the battle site, attackers often constructed the heavy and clumsy weapons shown here. Siege Tower Battering Ram Trebuchet • had a platform on top that lowered like a drawbridge • made of heavy timber with a sharp metal tip • worked like a giant slingshot • could support weapons and soldiers • swung like a pendulum to crack castle walls or to knock down drawbridge • propelled objects up to a distance of 980 feet Mantlet • shielded soldiers Tortoise • moved slowly on wheels • sheltered soldiers from falling arrows An Array of High-Flying Missiles Using the trebuchet, enemy soldiers launched a wide variety of missiles over the castle walls: • pots of burning lime • captured soldiers • boulders • diseased cows • severed human heads • dead horses 1. Making Inferences How do these Mangonel • flung huge rocks that crashed into castle walls RESEARCH LINKS For more on medieval weapons go to classzone.com 366 • propelled objects up to a distance of 1,300 feet siege weapons show that their designers knew the architecture of a castle well? See Skillbuilder Handbook, Page R16. 2. Drawing Conclusions What are some examples of modern weapons of war? What do they indicate about the way war is conducted today? Comparing How are tournaments like modern sports competitions? Vocabulary A siege is a military blockade staged by enemy armies trying to capture a fortress. After being dubbed a knight, most young men traveled for a year or two. The young knights gained experience fighting in local wars. Some took part in mock battles called tournaments. Tournaments combined recreation with combat training. Two armies of knights charged each other. Trumpets blared, and lords and ladies cheered. Like real battles, tournaments were fierce and bloody competitions. Winners could usually demand large ransoms from defeated knights. Brutal Reality of Warfare The small-scale violence of tournaments did not match the bloodshed of actual battles, especially those fought at castles. By the 1100s, massive walls and guard towers encircled stone castles. These castles dominated much of the countryside in western Europe. Lord and lady, their family, knights and other men-at-arms, and servants made their home in the castle. The castle also was a fortress, designed for defense. A castle under siege was a gory sight. Attacking armies used a wide range of strategies and weapons to force castle residents to surrender. Defenders of a castle poured boiling water, hot oil, or molten lead on enemy soldiers. Expert archers were stationed on the roof of the castle. Armed with crossbows, they fired deadly bolts that could pierce full armor. The Literature of Chivalry In the 1100s, the themes of medieval literature downplayed the brutality of knighthood and feudal warfare. Many stories idealized castle life. They glorified knighthood and chivalry, tournaments and real battles. Songs and poems about a knight’s undying love for a lady were also very popular. Epic Poetry Feudal lords and their ladies enjoyed listening to epic poems. These poems recounted a hero’s deeds and adventures. Many epics retold stories about legendary heroes such as King Arthur and Charlemagne. The Song of Roland is one of the earliest and most famous medieval epic poems. It praises a band of French soldiers who perished in battle during Charlemagne’s reign. The poem transforms the event into a struggle. A few brave French knights led by Roland battle an overwhelming army of Muslims from Spain. Roland’s friend, Turpin the Archbishop, stands as a shining example of medieval ideals. Turpin represents courage, faith, and chivalry: PRIMARY SOURCE And now there comes the Archbishop. He spurs his horse, goes up into a mountain, summons the French; and he preached them a sermon: “Barons, my lords, [Charlemagne] left us in this place. We know our duty: to die like good men for our King. Fight to defend the holy Christian faith.” from The Song of Roland Love Poems and Songs Under the code of chivalry, a knight’s duty to his lady became as important as his duty to his lord. In many medieval poems, the hero’s difficulties resulted from a conflict between those two obligations. Troubadours were traveling poet-musicians at the castles and courts of Europe. They composed short verses and Epic Films The long, narrative epic poem has given way in modern times to the epic film. Epic films feature largerthan-life characters in powerful stories that deal with mythic and timeless themes. These films take their stories from history, legend, and fantasy. The first epic film was Birth of a Nation, released in 1915. Some modern epic films are Braveheart (1995), pictured above; Gladiator (2000); and the Star Wars saga (six films, 1977–2005). INTERNET ACTIVITY Research five epic films. Write a one-sentence description of the historical content for each. Go to classzone.com for your research. European Middle Ages 367 songs about the joys and sorrows of romantic love. Sometimes troubadours sang their own verses in the castles of their lady. They also sent roving minstrels to carry their songs to courts. A troubadour might sing about love’s disappointments: “My loving heart, my faithfulness, myself, my world she deigns to take. Then leave me bare and comfortless to longing thoughts that ever wake.” Other songs told of lovesick knights who adored ladies they would probably never win: “Love of a far-off land/For you my heart is aching/And I can find no relief.” The code of chivalry promoted a false image of knights, making them seem more romantic than brutal. In turn, these love songs created an artificial image of women. In the troubadour’s eyes, noblewomen were always beautiful and pure. The most celebrated woman of the age was Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122–1204). Troubadours flocked to her court in the French duchy of Aquitaine. Later, as queen of England, Eleanor was the mother of two kings, Richard the Lion-Hearted and John. Richard himself composed romantic songs and poems. Women’s Role in Feudal Society Most women in feudal society were powerless, just as most men were. But women had the added burden of being thought inferior to men. This was the view of the Church and was generally accepted in feudal society. Nonetheless, women Daily Life of a Noblewoman Daily Life of a Peasant Woman This excerpt describes the daily life of an English noblewoman of the Middle Ages, Cicely Neville, Duchess of York. A typical noblewoman is pictured below. This excerpt describes the daily life of a typical medieval peasant woman as pictured below. PRIMARY SOURCE She gets up at 7a.m., and her chaplain is waiting to say morning prayers . . . and when she has washed and dressed . . . she has breakfast, then she goes to the chapel, for another service, then has dinner. . . . After dinner, she discusses business . . . then has a short sleep, then drinks ale or wine. Then . . . she goes to the chapel for evening service, and has supper. After supper, she relaxes with her women attendants. . . . After that, she goes to her private room, and says nighttime prayers. By 8 p.m. she is in bed. DAILY ROUTINE OF CICELY, DUCHESS OF YORK, quoted in Women in Medieval Times by Fiona Macdonald PRIMARY SOURCE I get up early . . . milk our cows and turn them into the field. . . . Then I make butter. . . . Afterward I make cheese. . . . Then the children need looking after. . . . I give the chickens food . . . and look after the young geese. . . . I bake, I brew. . . . I twist rope. . . . I tease out wool, and card it, and spin it on a wheel. . . . I organize food for the cattle, and for ourselves. . . . I look after all the household. FROM A BALLAD FIRST WRITTEN DOWN IN ABOUT 1500, quoted in Women in Medieval Times by Fiona Macdonald DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTIONS 1. Drawing Conclusions What seem to be the major concerns in the noblewoman’s life? How do they compare with those of the peasant woman? 2. Making Inferences What qualities would you associate with the peasant woman and the life she lived? 368 Chapter 13 played important roles in the lives of both noble and peasant families. Noblewomen Under the feudal system, a noble- woman could inherit an estate from her husband. Upon her lord’s request, she could also send his knights to war. When her husband was off fighting, the lady of a medieval castle might act as military commander and a warrior. At times, noblewomen played a key role in defending castles. They hurled rocks and fired arrows at attackers. (See the illustration to the right.) In reality, however, the lives of most noblewomen were limited. Whether young or old, females in noble families generally were confined to activities in the home or the convent. Also, noblewomen held little property because lords passed down their fiefs to sons and not to daughters. Summarizing What privileges did a noblewoman have in medieval society? SECTION Peasant Women For the vast majority of women of the lower classes, life had remained unchanged for centuries. Peasant women performed endless labor around the home and often in the fields, bore children, and took care of their families. Young peasant girls learned practical household skills from their mother at an early age, unlike daughters in rich households who were educated by tutors. Females in peasant families were poor and powerless. Yet, the economic contribution they made was essential to the survival of the peasant household. As you have read in this section, the Church significantly influenced the status of medieval women. In Section 4, you will read just how far-reaching was the influence of the Church in the Middle Ages. 3 ▲ The noblewomen depicted in this manuscript show their courage and combat skills in defending a castle against enemies. ASSESSMENT TERMS & NAMES 1. For each term or name, write a sentence explaining its significance. • chivalry • tournament • troubadour USING YOUR NOTES MAIN IDEAS CRITICAL THINKING & WRITING 2. Which ideas associated with 3. What were two inventions 6. DEVELOPING HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE How important a chivalry have remnants in today’s society? Explain. from Asia that changed the technology of warfare in western Europe? 7. MAKING INFERENCES How was the code of chivalry like 4. Who were the occupants of a 8. COMPARING AND CONTRASTING In what ways were the castle? Chivalry 5. What were some of the themes of medieval literature? role did knights play in the feudal system? the idea of romantic love? lives of a noblewoman and a peasant woman the same? different? 9. WRITING ACTIVITY RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS Write a persuasive essay in support of the adoption of a code of chivalry, listing the positive effects it might have on feudal society. CONNECT TO TODAY WRITING AN ADVERTISEMENT Conduct research to learn more about tournaments. Then, write a 50-word advertisement promoting a tournament to be held at a modern re-creation of a medieval fair. European Middle Ages 369 4 The Power of the Church MAIN IDEA POWER AND AUTHORITY Church leaders and political leaders competed for power and authority. WHY IT MATTERS NOW Today, many religious leaders still voice their opinions on political issues. TERMS & NAMES • clergy • sacrament • canon law • Holy Roman Empire • lay investiture SETTING THE STAGE Amid the weak central governments in feudal Europe, the Church emerged as a powerful institution. It shaped the lives of people from all social classes. As the Church expanded its political role, strong rulers began to question the pope’s authority. Dramatic power struggles unfolded in the Holy Roman Empire, the scene of mounting tensions between popes and emperors. TAKING NOTES Following Chronological Order List the significant dates and events for the Holy Roman Empire. Date/Event The Far-Reaching Authority of the Church In crowning Charlemagne as the Roman Emperor in 800, the Church sought to influence both spiritual and political matters. Three hundred years earlier, Pope Gelasius I recognized the conflicts that could arise between the two great forces— the Church and the state. He wrote, “There are two powers by which this world is chiefly ruled: the sacred authority of the priesthood and the authority of kings.” Gelasius suggested an analogy to solve such conflicts. God had created two symbolic swords. One sword was religious. The other was political. The pope held a spiritual sword. The emperor wielded a political one. Gelasius thought that the pope should bow to the emperor in political matters. In turn, the emperor should bow to the pope in religious matters. If each ruler kept the authority in his own realm, Gelasius suggested, the two leaders could share power in harmony. In reality, though, they disagreed on the boundaries of either realm. Throughout the Middle Ages, the Church and various European rulers competed for power. The Structure of the Church Like the system of feudalism, the Church had its own organization. Power was based on status. Church structure consisted of different ranks of clergy, or religious officials. The pope in Rome headed the Church. All clergy, including bishops and priests, fell under his authority. Bishops supervised priests, the lowest ranking members of the clergy. Bishops also settled disputes over Church teachings and practices. For most people, local priests served as the main contact with the Church. Religion as a Unifying Force Feudalism and the manor system cre- ated divisions among people. But the shared beliefs in the teachings of the Church bonded people together. The church was a stable force during an era of constant warfare and political turmoil. It provided Christians with a sense of security and of belonging to a religious community. In the Middle Ages, religion occupied center stage. 370 Chapter 13 ▼ A pope’s tiara symbolized his power. Analyzing Motives Why did medieval peasants support the Church? Medieval Christians’ everyday lives were harsh. Still, they could all follow the same path to salvation—everlasting life in heaven. Priests and other clergy administered the sacraments, or important religious ceremonies. These rites paved the way for achieving salvation. For example, through the sacrament of baptism, people became part of the Christian community. At the local level, the village church was a unifying force in the lives of most people. It served as a religious and social center. People worshiped together at the church. They also met with other villagers. Religious holidays, especially Christmas and Easter, were occasions for festive celebrations. The Law of the Church The Church’s authority was both An Age of Superstition religious and political. It provided a unifying set of spiritual beliefs and rituals. The Church also created a system of justice to guide people’s conduct. All medieval Christians, kings and peasants alike, were subject to canon law, or Church law, in matters such as marriage and religious practices. The Church also established courts to try people accused of violating canon law. Two of the harshest punishments that offenders faced were excommunication and interdict. Popes used the threat of excommunication, or banishment from the Church, to wield power over political rulers. For example, a disobedient king’s quarrel with a pope might result in excommunication. This meant the king would be denied salvation. Excommunication also freed all the king’s vassals from their duties to him. If an excommunicated king continued to disobey the pope, the pope, in turn, could use an even more frightening weapon, the interdict. Under an interdict, many sacraments and religious services could not be performed in the king’s lands. As Christians, the king’s subjects believed that without such sacraments they might be doomed to hell. In the 11th century, excommunication and the possible threat of an interdict would force a German emperor to submit to the pope’s commands. Lacking knowledge of the laws of nature, many people during the Middle Ages were led to irrational beliefs. They expected the dead to reappear as ghosts. A friendly goblin might do a person a good deed, but an evil witch might cause great harm. Medieval people thought an evil witch had the power to exchange a healthy child for a sickly one. The medieval Church frowned upon superstitions such as these: • preparing a table with three knives to please good fairies • making a vow by a tree, a pond, or any place but a church • believing that a person could change into the shape of a wolf • believing that the croak of a raven or meeting a priest would bring a person good or bad luck The Church and the Holy Roman Empire When Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne emperor in 800, he unknowingly set the stage for future conflicts between popes and emperors. These clashes would go on for centuries. Otto I Allies with the Church The most effective ruler of medieval Germany was Otto I, known as Otto the Great. Otto, crowned king in 936, followed the policies of his hero, Charlemagne. Otto formed a close alliance with the Church. To limit the nobles’ strength, he sought help from the clergy. He built up his power base by gaining the support of the bishops and abbots, the heads of monasteries. He dominated the Church in Germany. He also used his power to defeat German princes. Following in Charlemagne’s footsteps, Otto also invaded Italy on the pope’s behalf. In 962, the pope rewarded Otto by crowning him emperor. Signs of Future Conflicts The German-Italian empire Otto created was first called the Roman Empire of the German Nation. It later became the Holy Roman Empire. It remained the strongest state in Europe until about 1100. However, European Middle Ages 371 Otto’s attempt to revive Charlemagne’s empire caused trouble for future German leaders. Popes and Italian nobles, too, resented German power over Italy. The Emperor Clashes with the Pope The Church was not happy that kings, such as Otto, had control over clergy and their offices. It especially resented the practice of lay investiture, a ceremony in which kings and nobles appointed church officials. Whoever controlled lay investiture held the real power in naming bishops, who were very influential clergy that kings sought to control. Church reformers felt that kings should not have that power. In 1075, Pope Gregory VII banned lay investiture. The furious young German emperor, Henry IV, immediately called a meeting of the German bishops he had appointed. With their approval, the emperor ordered Gregory to step down from the papacy. Gregory then excommunicated Henry. Afterward, German bishops and princes sided with the pope. To save his throne, Henry tried to win the pope’s forgiveness. Showdown at Canossa In January 1077, Henry crossed the snowy Alps to the Italian town of Canossa (kuh•NAHS•uh). He approached the castle where Gregory was a guest. Gregory later described the scene: PRIMARY SOURCE There, having laid aside all the belongings of royalty, wretchedly, with bare feet and clad in wool, he [Henry IV] continued for three days to stand before the gate of the castle. Nor did he desist from imploring with many tears the aid and consolation of the apostolic mercy until he had moved all of those who were present there. POPE GREGORY, in Basic Documents in Medieval History The Holy Roman Empire, 1100 16°E 8°E 0° 24°E 0 Friesland . Franconia Worms FRANCE 400 Kilometers POLAND eR Lorraine 0 Saxony E lb ne R. Rhi Aachen 50°N 200 Miles Swabia KINGDOM OF HUNGARY Bavaria Rhône R. Burgundy Carinthia Lombardy Po R. Tuscany Spoleto c ti Rome ria Mediterranean Sea The Holy Roman Empire Papal States Ad Papal States 42°N Concordat of Worms The succes- Bohemia Danube R . Se a GEOGRAPHY SKILLBUILDER: Interpreting Maps 1. Region How many states made up the Holy Roman Empire? What does this suggest about ruling it as an empire? 2. Location How did the location of the Papal States make them an easy target for frequent invasions by Germanic rulers? 372 The Pope was obligated to forgive any sinner who begged so humbly. Still, Gregory kept Henry waiting in the snow for three days before ending his excommunication. Their meeting actually solved nothing. The pope had humiliated Henry, the proudest ruler in Europe. Yet, Henry felt triumphant and rushed home to punish rebellious nobles. sors of Gregory and Henry continued to fight over lay investiture until 1122. That year, representatives of the Church and the emperor met in the German city of Worms (wurms). They reached a compromise known as the Concordat of Worms. By its terms, the Church alone could appoint a bishop, but the emperor could veto the appointment. During Henry’s struggle, German princes regained power lost under Otto. But a later king, Frederick I, would resume the battle to build royal authority. Making Inferences Why was Henry’s journey to Canossa a political act? Disorder in the Empire By 1152, the seven princes who elected the German king realized that Germany needed a strong ruler to keep the peace. They chose Frederick I, nicknamed “Barbarossa” for his red beard. Vocabulary Barbarossa means “red beard” in Italian. The Reign of Frederick I Frederick I was the first ruler to call his lands the Holy Roman Empire. However, this region was actually a patchwork of feudal territories. His forceful personality and military skills enabled him to dominate the German princes. Yet, whenever he left the country, disorder returned. Following Otto’s example, Frederick repeatedly invaded the rich cities of Italy. His brutal tactics spurred Italian merchants to unite against him. He also angered the pope, who joined the merchants in an alliance called the Lombard League. In 1176, the foot soldiers of the Lombard League faced Frederick’s army of mounted knights at the Battle of Legnano (lay•NYAHN•oh). In an astonishing victory, the Italian foot soldiers used crossbows to defeat feudal knights for the first time in history. In 1177, Frederick made peace with the pope and returned to Germany. His defeat, though, had undermined his authority with the German princes. After he drowned in 1190, his empire fell to pieces. German States Remain Separate German kings after Frederick, including his grandson Frederick II, continued their attempts to revive Charlemagne’s empire and his alliance with the Church. This policy led to wars with Italian cities and to further clashes with the pope. These conflicts were one reason why the feudal states of Germany did not unify during the Middle Ages. Another reason was that the system of German princes electing the king weakened royal authority. German rulers controlled fewer royal lands to use as a base of power than French and English kings of the same period, who, as you will learn in Chapter 14, were establishing strong central authority. Analyzing Causes What political trend kept German states separate during the Middle Ages? SECTION 4 ▲ This manuscript shows Frederick I at the height of his imperial power. ASSESSMENT TERMS & NAMES 1. For each term or name, write a sentence explaining its significance. • clergy • sacrament • canon law • Holy Roman Empire • lay investiture USING YOUR NOTES MAIN IDEAS CRITICAL THINKING & WRITING 2. Which of the events were 3. What were some of the matters 6. COMPARING How was the structure of the Church like power struggles between the Church and rulers? Explain. Date/Event covered by canon law? 4. How did Otto the Great make the crown stronger than the German nobles? 5. Why did lay investiture cause a struggle between kings and popes? that of the feudal system? 7. EVALUATING DECISIONS Was the Concordat of Worms a fair compromise for both the emperor and the Church? Why or why not? 8. DRAWING CONCLUSIONS Why did German kings fail to unite their lands? 9. WRITING ACTIVITY POWER AND AUTHORITY Why did Henry IV go to Canossa to confront Pope Gregory VII? Write a brief dialogue that might have taken place between them at their first meeting. CONNECT TO TODAY CREATING A CHART Research the ruling structure of the modern Roman Catholic Church and then create a chart showing the structure, or hierarchy. European Middle Ages 373 Chapter 13 Assessment TERMS & NAMES The Power of the Church Section 4 (pages 370–373) 18. What was Gelasius’s two-swords theory? For each term or name below, briefly explain its connection to the Middle Ages from 500 to 1200. 1. monastery 5. manor 2. Charlemagne 6. chivalry 3. vassal 7. clergy 4. serf 8. Holy Roman Empire 19. Why was Otto I the most effective ruler of Medieval Germany? 20. How was the conflict between Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV resolved? CRITICAL THINKING MAIN IDEAS Charlemagne Unites Germanic Kingdoms Section 1 (pages 353–357) 9. How did Gregory I increase the political power of the pope? 10. What was the outcome of the Battle of Tours? 11. What was the significance of the pope’s declaring Charlemagne emperor? 12. Which invading peoples caused turmoil in Europe during the 800s? 14. What duties did the lord of a manor and his serfs owe one another? The Age of Chivalry Section 3 (pages 364–369) 15. What were the stages of becoming a knight? 16. What were common subjects of troubadours’ songs? 17. What role did women play under feudalism? Medieval Europe government religion social roles 2. COMPARING AND CONTRASTING EMPIRE BUILDING How did Otto I and Frederick I try to imitate Charlemagne’s approach to empire building? Feudalism in Europe Section 2 (pages 358–363) 13. What exchange took place between lords and vassals under feudalism? 1. USING YOUR NOTES In a chart, compare medieval Europe to an earlier civilization, such as Rome or Greece. Consider government, religion, and social roles. 3. DRAWING CONCLUSIONS POWER AND AUTHORITY Why do you think the ownership of land became an increasing source of power for feudal lords? 4. ANALYZING ISSUES Why did the appointment of bishops become the issue in a struggle between kings and popes? 5. SYNTHESIZING RELIGIOUS AND ETHICAL SYSTEMS What generalizations could you make about the relationship between politics and religion in the Middle Ages? European Middle Ages Economic System Code of Behavior Manors • • Lord’s estate Set of rights and obligations between serfs and lords • Chivalry Belief System • • The Church Power over people’s • Involvement in everyday lives political affairs Unifying force of Christian faith 374 Chapter 13 • Displays of courage • Devotion to a Self-sufficient community producing a variety of goods and valor in combat feudal lord and heavenly lord • Respect toward women MEDIEVAL SOCIETY Political System • • DEE D Feudalism Form of govern• Oaths of loyalty in ment based on exchange for land landholding and military service Alliances between lords and vassals • Ranking of power and authority Use the quotation and your knowledge of world history to answer questions 1 and 2. Additional Test Practice, pp. S1-S33 Use the bar graph and your knowledge of world history to answer question 3. Population of Three Roman Cities 1. Which of these phrases does not characterize the knight Chaucer describes? A. a skilled fighter 350 Population (in thousands) There was a knight, a most distinguished man, Who from the day on which he first began To ride abroad had followed chivalry, Truth, honor, generous, and courtesy. He had done nobly in sovereign’s war And ridden in battle, no man more, As well as Christian in heathen places And ever honored for his noble graces. GEOFFREY CHAUCER, The Canterbury Tales 300 250 200 150 100 50 0 B. a devoted Christian D. a well-traveled warrior A. that a knight was of noble birth B. that a knight was a skilled warrior C. that a knight adored his chosen lady D. that a knight devoted himself to his heavenly Lord Lyon Trier (in France) (in Germany) City Populations around A.D. 100 City Populations around A.D. 900 C. a young man 2. What qualities of knighthood do you think are missing from Chaucer’s description? Rome Sources: Man and History; 3,000 Years of Urban Growth 3. What is the most important point this chart is making? A. Trier and Lyon were not as large as Rome. B. Rome was the most populous city in the Roman Empire. C. All three cities lost significant population after the fall of the Roman Empire. D. Rome lost about 300,000 people from A.D. 100 to A.D. 200. TEST PRACTICE Go to classzone.com • Diagnostic tests • Strategies • Tutorials • Additional practice ALTERNATIVE ASSESSMENT 1. Interact with History On page 352, you considered the issue of what freedoms you would give up for protection. Now that you have read the chapter, reconsider your answer. How important was security? Was it worth not having certain basic freedoms? Discuss your ideas in a small group. 2. WRITING ABOUT HISTORY Refer to the text, and then write a three-paragraph character sketch of a religious or political figure described in this chapter. Consider the following: Designing a Video Game Use the Internet, books, and other reference materials to find out more about medieval tournaments. Then create a video game that imitates a medieval tournament between knights. Describe your ideas in a proposal that you might send to a video game company. Think about video games that are based on contests. You might adapt some of the rules to your game. Consider the following: • the rules of the game • why the figure was important • the system of keeping score of wins and losses • how the figure performed his or her role • weapons that should be used European Middle Ages 375