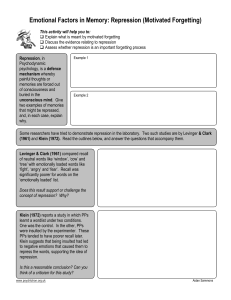

The unified theory of repression

advertisement