cybersecurity cs-secondary version - K-12 Program

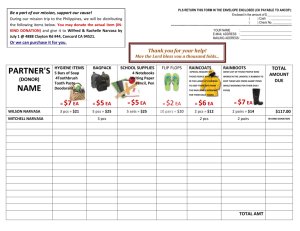

advertisement

THE NATION’S NEWSPAPER Secondary Case Study How to keep your personal information safe By Mary Beth Marklein ..........................................................................................4 Malicious-software predators get sneakier, more prevalent By Byron Acohido and Jon Swartz ..........................................................................................5-8 Cyber Security Awareness New communication technologies provide many great opportunities; however, there is always the potential that someone will misuse that technology to take illegal advantage of a user. It is important for students, educators and parents to have a basic awareness and knowledge about being responsible and safe when creating online profiles, blogging, using instant messaging services or socializing on the Web. As the number of registered members and online activity continues to increase on social networking sites, budding cyberthieves also increase. This case study provides examples of some potential online dangers and offers recommendations on how to protect your personal information while networking safely and wisely. Data miners dig a little deeper Companies may know a lot more about you than you think — or want Some ‘script kiddies’ get more attention than others By Jon Swartz and Byron Acohido ..........................................................................................9 Discussion questions, activity and additional resources By Michelle Kessler and Byron Acohido USA TODAY ..........................................................................................10 SAN FRANCISCO — When customers sign up for a free Hotmail e-mail account from Microsoft, they're required to submit their name, age, gender and ZIP code. USA TODAY Snapshots® What actions should the U.S. government take to better safeguard cyberspace? Establish better communication with and among the private sector 71% Educate people about cybersecurity roles and capabilities 71% Make cybersecurity a greater priority 70% Educate critical infrastructures on cybersecurity risks and how to respond to cyberemergencies 68% By Alejandro Gonzalez, USA TODAY Note: Multiple responses allowed 1 – Oil & gas, nuclear, energy, water or other critical industries Source: CSO magazine survey of 389 chief security officers and security executives. Margin of error ±5 percentage points. By Jae Yang and Sam Ward, USA TODAY But that's not all the software giant knows about them. Microsoft takes notice of what time of day they access their inboxes. And it goes to the trouble of finding out how much money folks in their neighborhood earn. Why? It knows a florist will pay a premium to have a coupon for roses reach males 30-40, earning good wages, who check their e-mail during lunch hour on Valentine's Day. © Copyright 2006 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. All rights reser ved. AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, JULY 12, 2006 Stores’ loyalty cards offer a wealth of information about shoppers Microsoft is one of many companies collecting and aggregating data in new ways so sophisticated that many customers may not even realize they're being watched. These businesses are using new software tools that can record every move a person makes online and combine that information with other data. Brick-and-mortar stores, afraid of being left behind, are ramping up data collection and processing efforts, too, says JupiterResearch analyst Patti Freeman Evans. The result: Corporate America is creating increasingly detailed portraits of each consumer, whether they're aware of it or not. Companies say they can be trusted to do so responsibly. Yahoo, for instance, has a strict ban on selling data from its customer registration lists. And Microsoft says it won't purchase an individual's income histor y — just the average income from his or her ZIP code. "We're making sure there's a very bright line in the sand," says spokesman Joe Doran. Some consumers aren't reassured. Salt Lake City lighting designer Jody Good, 54, goes to great lengths to control his personal information, including signing up for some services with false names and keeping unusually tight security settings on his PC. "I'm trying to preserve my privacy," he says. Privacy advocates are worried, too. "Think about it: A handful of powerful entities know a tremendous amount of information about you," says Jeff Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy. "Today they manipulate you into what kind of soap to buy, tomorrow it might be who you should pray for or who you should vote for." Data mining grows Worldwide advanced analytics software market: (in billions) $2.0 $1.6 $0.9 $1.2 $0.8 $0.4 0 ’00 ’01 ’02 ’03 Online advertising revenue (in billions) $1.8 ’04 ’05 $12.54 $12 $8.09 $8 $4 0 ’00 ’01 ’02 ’03 ’04 ’05 Sources: IDC and Interactive Advertising Bureau/Price Waterhouse Coopers By Adrienne Lewis, USA TODAY Targeting behavior Internet firms are at the vanguard of the trend through a technique called behavioral targeting. It works like this: Anyone who has registered to use any of Yahoo's free online services can be sure the tech company is paying close attention to everything they do within its network. It will notice, for instance, who uses Yahoo search to find information on SUVs. Why? It wants to sell targeted ads to SUV makers and auto loan brokers that will appear, say, on Yahoo Finance the next time that person checks his or her stocks. Online retailers target, too, usually by placing a small data file called a cookie on a customer's computer. The cookie keeps track of where you go each time you are on the site. Hewlett-Packard's online store uses cookies to remind customers of items viewed in previous visits — no matter how much time has elapsed between them. Targeting isn't new. In 2000, online advertiser DoubleClick ignited a public uproar when it announced plans to cross-reference anonymous Web-surfing data with personal data collected by offline data broker Abacus Direct. Congress held hearings, and DoubleClick backed off. But, as online advertising soars, "We're hitting the tipping point," says Bill Gossman, CEO of Revenue Science. Merrill Lynch estimates the online ad market will grow 29% this year topping $16 billion. Researcher eMarketer estimates advertisers will spend about $1.2 billion on targeted online advertising this year and more than $2 billion by 2008. A phalanx of online marketing Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 2 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, JULY 12, 2006 specialists, including Tacoda, Revenue Science, AlmondNet, advertising.com, DrivePM and Did-it, are pushing it. They're hustling to form overlapping alliances with major media website publishers. "Targeting has certainly become a large part of what advertisers are interested in," says Yahoo spokeswoman Nissa Anklesaria. Targeting advocates herald the win-win-win. Publishers can charge more for relevant ads that spur sales and decrease annoyances. Microsoft says it can help a Dinners-To-Go franchisee zero in on working moms, age 30 to 40, in a given neighborhood, with ads designed to reach them before 10a.m., when they are likely to be planning the evening meal. "Instead of carpet bombing, it's more of a shotgun approach where you're hoping to hit the targeted customer," say Doran. But there's one big holdout: search giant Google. Although the company scans customers' Google e-mail accounts in order to send them text ads, it hasn't yet embraced more proactive targeting. "We're treading very carefully in this space because we put user trust foremost," says Google product manager Richard Holden. Rewarding loyalty Brick-and-mortar companies are working hard to create similarly rich data sources. Although they can't track a customer's every move, they can create basic profiles of them using loyalty cards. Loyalty cards are typically given to customers in exchange for personal information. In return, customers get coupon-like discounts when they present their card. Safeway helped kick off the loyalty-card era in 1998, and was soon followed by rivals such as Albertsons and Kroger. Many programs are run behind the scenes by a little-known Florida firm called Catalina Marketing. Catalina collects loyalty and bulk sales data from more than 20,000 stores, then uses it to create pictures of shoppers over time, says CEO L. Dick Buell. The picture gets clearer the more data stores collect. For example, Catalina can help retailers determine that someone lives in an upscale area, buys diapers, and may be interested in high-end baby food. The data Catalina receives do not contain personal information. Records are identified by an ID number only. But retailers hang on to personal information and can reattach it to records once getting them back from Catalina. That worries privacy advocates, because loyalty cards — fairly rare a few years ago — are spreading fast. Most large grocery chains except Wal-Mart have them. And they're moving beyond grocery stores, to outlets such as Barnes & Noble bookstores, CVS drugstores, and Exxon and Mobil gas stations. Mining for data The flood of new information is helping spawn a sister industry: data-mining software. These powerful programs sort through massive databases, looking for patterns that would take a human years to spot. Sales of data-crunching software have jumped more than 30% since 2000 and are expected to keep growing, says tech analyst Dan Vesset with researcher IDC. "Most large companies are doing it in one area or another," says tech analyst Gareth Herschel with researcher Gartner. In its most basic form, data mining is simple. A grocery store might put the peanut butter next to the jelly one week, and move it to a different aisle the following week. The store can then run data-mining software on the two weeks' sales receipts to learn which setup sold more peanut butter. Technology always improving But far more sophisticated and complex types of mining are emerging. Silicon Valley firm Sigma Dynamics has launched software that can analyze data on the fly, even if it's not stored in neat columns and rows. For example, it can read the typed notes of a customer service agent, compare them with a database of stored records, and see if any phrases match. Then it can instantly pop up a window offering a solution to the customer's problem. Entrepreneur Jeff Jonas has created software that starts by examining the record of a known entity — usually a person. It then compares that record to thousands of others, looking for patterns that might signify a relationship. Jonas designed the software for Las Vegas casinos, which wanted to better know who their customers were — in part to keep out cheats. The software could identify relationships that might otherwise go unnoticed, such as the fact that a cheater and a casino employee were roommates. The Central Intelligence Agency realized that the software could have other applications. Its venture capital arm, In-Q-Tel, funded Jonas' small company in 2001. IBM bought it in 2005 and now sells the program to businesses, including retailers and financial institutions. Other companies are working to make data mining — traditionally a high-tech discipline of statisticians and programmers — accessible to average workers. One such firm, Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 3 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, JULY 12, 2006 San Francisco data-mining software maker KXEN, says there's a huge demand. Data-mining technology "has been used for a long time, but only by a very small number of people," says President Ken Bendix. Although companies have long had useful data, the information was rarely used to its full potential, he says. Now that's starting to change. But the growth in data mining creates a problem, says Stanford University professor Hector Garcia-Molina. "How can you provide that kind of useful information without violating the privacy of individuals?" he asks. Garcia-Molina is working on computer science tools that will keep databases from extracting too much personal information while slicing and dicing. The work, still in its experimental phase, "is not easy," he admits. IBM's Jonas proposes a lower-tech solution — better disclosure. Most companies do have privacy policies today, but they're generally vague, he says. "I would like to do business with companies who are using my data the way I expect them to," he says. "I want to avoid surprise." Jeff Barnum, a 45-year-old real estate consultant from Cincinnati, agrees. He avoids filling out many forms and frequently deletes cookies from his PC, yet is willing to share his information with companies he trusts. Barnum says his clients do the same. When visiting an open house, many people give him false names and other information. But once they get to know him, "They'll tell me anything," he says, laughing. AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S LIFE SECTION, AUGUST 2, 2006 How to keep your personal information safe By Mary Beth Marklein USA TODAY locked box so even your roommate can't get it. No one knows for sure how many college students have been victims of identity theft, but they are popular targets. Federal Trade Commission data show that 18- to 24-year-olds are the second-highest-risk group, after ages 25 to 34. u Add a shredder to your list of backto-school needs. u Don't use your Social Security number for any reason other than tax and employment, to get a line of credit or for student loan applications. If your school uses your Social Security number as an identifier — whether it's on your student ID or a professor posting grades by Social Security number — lobby to change the policy. Students are attractive candidates in part because they are typically transient and have less credit history than more established adults. That makes it more difficult to distinguish between a legitimate credit application and a fraudulent one, says Mike Cook of ID Analytics, a San Diego identity risk management company. "If you're going to steal an identity, a student identity is a very good one to steal," he says. Also, college students create risks for themselves. The popularity of social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace has led to concerns that students disclose too much information about themselves without taking stock By Web Bryant, USA TODAY of the potential dangers of such activity. A number of organizations, from the Federal Trade Commission to individual colleges, are developing campaigns aimed at helping consumers protect themselves. Linda Foley of the San Diego-based Identity Theft Resource Center offers these tips for students: u Keep personal information in a u Don't be tempted by free T-shirts or other incentives to apply for credit cards at a table set up on campus. u Know what the scams are, and don't respond to them. (One popular online scam called "phishing" involves a thief posing as a legitimate business asking you to provide sensitive data so they can "update their files" or "protect your data.") This month, Foley's group will unveil a teen information program on its website. It will be available at www.idtheftcenter.org. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 4 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, APRIL 24, 2006 Malicious-software spreaders get sneakier, more prevalent So-called bot herders team with organized crime to steal identities, account info In separate cases, federal authorities last August also assisted in the arrest of Farid Essebar, 18, of Morocco, and last month indicted Christopher Maxwell, 19, of Vacaville, Calif., on suspicion of similar activities. The arrests underscore an ominous shift in the struggle to keep the Internet secure: Cybercrime undergirded by networks of bots — PCs infected with malicious software that allows them to be controlled by an attacker — is soaring. Without you realizing it, attackers are secretly trying to penetrate your PC to tap small bits of computing power to do evil things. They've already compromised some 47 million PC's sitting in living rooms, in your kids' bedrooms, even on the desk in your office. By Byron Acohido and Jon Swartz USA TODAY SEAT TLE — At the height of his powers, Jeanson James Ancheta felt unstoppable. From his home in Downey, Calif., the then-19-year-old high school dropout controlled thousands of compromised PCs, or "bots," that helped him earn enough cash in 2004 and 2005 to drive a souped-up 1993 BMW and spend $600 a week on new clothes and car parts. He once bragged to a protege that hacking Internetconnected PCs was "easy, like slicing cheese," court records show. But Ancheta got caught. In the first case of its kind, he pleaded guilty in January to federal charges of hijacking hundreds of thousands of computers and selling access to others to spread spam and launch Web attacks. Bot networks have become so ubiquitous that they've also given rise to a new breed of low-level bot masters, typified by Ancheta, Essebar and Maxwell. Tim Cranton, director of Microsoft's Internet Safety Enforcement Team, calls bot networks "the tool of choice for those intent on using the Internet to carry out crimes." Budding cyberthieves use basic programs and generally stick to quick-cash schemes. Brazen and inexperienced, they can inadvertently cause chaos: Essebar is facing prosecution in Morocco on charges of releasing the Zotob worm that crippled systems in banks and media companies around the world; Maxwell awaits a May 15 trial for allegedly spreading bots that disrupted operations at Seattle's Northwest Hospital. More elite bot herders, who partner with crime groups to supply computer power for data theft and other cyberfraud, have proved to be highly elusive. But the neophytes tend to be sloppy about hiding their tracks. The investigations leading to the arrests of Ancheta, Essebar and Maxwell have given authorities their most detailed look yet at how bots enable cybercrime. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 5 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, APRIL 24, 2006 Low-level cybercrooks much more likely than elite ones to get caught Estimating the number of bots is difficult, but top researchers who participate in meetings of high-tech's Messaging Anti-Abuse Working Group often use a 7% infection rate as a discussion point. That means as many as 47 million of the 681 million PCs connected to the Internet worldwide may be under the control of a bot network. Security giant McAfee detected 28,000 distinct bot networks active last year, more than triple the amount in 2004. And a Februar y sur vey of 123 tech executives, conducted by security firm nCircle, pegged annual losses to U.S. businesses because of computer-related crimes at $197 billion. Law enforcement officials say the ground floor is populated by perhaps hundreds of bot herders, most of them young men. Mostly, they assemble networks of compromised PCs to make quick cash by spreading adware -- those pop-up advertisements for banking, dating, porn and gambling websites that clutter the Internet. They get paid for installing adware on each PC they infect. "The low-level guys … can inflict a lot of collateral damage," says Steve Martinez, deputy assistant director of the FBI's Cyber Division. Ancheta and his attorney declined to be interviewed, and efforts to reach Essebar with help from the FBI were unsuccessful. Steven Bauer, Maxwell's attorney, said his client was a "fairly small player" who began spreading bots "almost as a youthful prank." The stories of these three young men, pieced together from court records and interviews with regulators, security experts and independent investigators, illustrate the mind-set of the growing fraternity of hackers and cyberthieves born after 1985. They also provide a glimpse of Cybercrime Inc.'s most versatile and profitable tool. Ancheta: Trading candy School records show that Ancheta transferred out of Downey High School, in a suburb near Los Angeles, in December 2001 and later attended an alternative program for students with academic or behavioral problems. Eventually, he earned a high school equivalency certificate. Ancheta worked at an Internet cafe and expressed an interest in joining the military reserves, his aunt, Sharon Gregorio, told the Associated Press. Where the bots are Bot-infected PCs, by country rank: Jan.-June 2005 July-Dec. 2005 United Kingdom China France Instead, in June 2004, court records show, he discovered rxbot, a potent — but quite common — computer worm, malicious computer code designed to spread widely across the Internet. Ancheta likely gravitated to it because it is easy to customize, says Nicholas Albright, founder of Shadowserver.org, a watchdog group. Novices often start by tweaking worms and trading bots. "I see high school kids doing it all the time," says Albright. "They trade bot nets like candy." Ancheta proved more enterprising than most. He infected thousands of PCs and started a business — #botz4sale — on a private Internet chat area. From June to September 2004, he made about $3,000 on more than 30 sales of up to 10,000 bots at a time, according to court records. By late 2004, he started a new venture, court records show. He signed up with two Internet marketing companies, LoudCash of Bellevue, Wash., and GammaCash Entertainment of Montreal, to distribute ads on commission. But instead of setting up a website and asking visitors for permission to install ads — a common, legal practice — he used his bots to install adware on vulnerable Internet-connected PCs, court records show. Typically, payment for each piece of adware installed ranges from 20 19% 26% 32% 22% USA South Korea Canada Taiwan Spain Germany Japan 7% 9% 3.7% 4.4% 3.6% 3.8% 5% 3.8% 2.4% 2.7% 2.7% 2.6% 3.6% 2.6% 3% 2% Source: Symantec By Alejandro Gonzalez, USA TODAY cents to 70 cents. Working at home, Ancheta nurtured his growing bot empire during a workday that usually began shortly after 1 p.m. and stretched non-stop until 5 a.m., a source with direct knowledge of the case says. He hired an assistant, an admiring juvenile from Boca Raton, Fla., nicknamed SoBe, court records show. Chatting via AOL's free instant-messaging service, Ancheta taught him how to spread PC infections and manage adware installations. Checks ranging as high as $7,996 began rolling in from the two marketing firms. In six months, Ancheta and his helper Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 6 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, APRIL 24, 2006 pulled in nearly $60,000, court records show. What bots do victim must help, by clicking on an email attachment to start the infection. During one online chat with SoBe about installing adware, Ancheta, who awaits sentencing May 1, advised his helper: "It's immoral, but the money makes it right." Infected PCs that await commands, bots are being used for: Diabl0 created a ver y distinctive version of Mytob designed to lower the security settings on infected PCs, install adware and report back to Diabl0 for more instructions. Last June, David Taylor, an information security specialist at the University of Pennsylvania, spotted Diabl0 on the Internet as he was about to issue such instructions. Taylor engaged the hacker in a text chat. Sean Sundwall, a spokesman for Bellevue, Wash.-based 180solutions, LoudCash's parent company, said Ancheta distributed its adware in only a small number of incidents listed in the indictment. GammaCash had no comment. Maxwell: Infecting a hospital At about the same time — in early 2005 — Christopher Maxwell and two coconspirators were allegedly hitting their stride running a similar operation. From his parents' home in Vacaville, Calif., Maxwell, then an 18-year-old community college student, conspired with two minors in other states to spread bots and install adware, earning $100,000 from July 2004 to July 2005, according to a federal indictment. They ran into a problem in January 2005 when a copy of the bot they were using inadvertently found its way onto a vulnerable PC at Seattle's Northwest Hospital. Once inside the hospital's network, it swiftly infected 150 of the hospital's 1,100 PCs and would have compromised many more. But the simultaneous scanning of 150 PCs looking for other machines to infect overwhelmed the local network, according to an account in court records. Computers in the intensive care unit shut down. Lab tests and administrative tasks were interrupted, forcing the hospital into manual procedures. Over the next few months, special agent David Farquhar, a member of the FBI's Northwest Cyber Crime Task Force, traced the infection to a NetZero Internet account using a phone number at Maxwell's parents' home, leading to u Spamming. Bots deliver 70% of nuisance e-mail ads. u Phishing. Bots push out e-mail scams that lure victims into divulging log-ons and passwords. u Denial-of-service attacks. Bots flood targeted websites with nuisance requests, shutting them down. To stop such attacks, website operators are coerced into making extortion payments. Diabl0 boasted about using Mytob to get paid for installing adware. "I really thought that he was immature," Taylor recalls. "He was asking me what did I think about his new bot, with all these smiley faces. Maybe he didn't realize what he was doing was so bad." u Self-propagation. Bots scour the Internet for other PCs to infect; they implant password breakers and packet sniffers that continually probe for routes to drill deeper into corporate systems. In early August, Diabl0 capitalized on a golden opportunity when Microsoft issued its monthly set of patches for newly discovered security holes in Windows. As usual, independent researchers immediately began to analyze the patches as part of a process to develop better security tools. Cybercrooks closely monitor the public websites where results of this kind of research get posted. u Direct theft. Bots implant keystroke loggers and man-in-the-middle programs that record when the PC user types in account log-on information, then transmit the data back to the bot master. Maxwell's indictment on Feb. 9. He pleaded not guilty. Essebar: Birth of a worm As authorities closed in on Ancheta and Maxwell last summer, 18-year-old Farid Essebar was allegedly just getting started in the bots marketplace. The FBI says the skinny, Russian-born resident of Morocco operated under the nickname Diabl0 (pronounced Diablo but spelled with a zero). Diabl0 began attracting notice as one of many copycat hackers tweaking the ubiquitous Mytob e-mail worm. E-mail worms compromise a PC in much the same way as a bot, but the Diabl0 latched onto one of the test tools and turned it into a self-propagating worm, dubbed Zotob, says Charles Renert, director of research at security firm Determina. Much like Mytob, Zotob prepared the infected PC to receive adware. But Zotob did one better: It could sweep across the Internet, infecting PCs with no user action required. Diabl0 designed Zotob to quietly seek out certain Windows computer servers equipped with the latest compilation of upgrades, called a service pack. But he failed to account for thousands of Windows servers still running outdated service packs, says Peter Allor, director of intelligence at Internet Security Systems. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. By the start of the next workweek, Page 7 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, APRIL 24, 2006 Zotob variants began snaking into older servers at the Canadian bank CIBC, and at ABC News, The New York Times and CNN. The servers began rebooting repeatedly, disrupting business and drawing serious attention to the new worm. "Zotob had a quality-assurance problem," says Allor. Diabl0 had neglected to ensure Zotob would run smoothly on servers running the earlier service packs, he says. Within two weeks, Microsoft's Internet Safety Enforcement Team, a group of 65 investigators, paralegals and lawyers, identified Essebar as Diabl0 and pinpointed his base of operations. Microsoft's team also flushed out a suspected accomplice, Atilla Ekici, 21, nicknamed Coder. Microsoft alerted the FBI, which led to the Aug. 25 arrests by local authorities of Essebar in Morocco and Ekici in Turkey. The FBI holds evidence that Ekici paid Essebar with stolen credit card numbers to create the Mytob variants and Zotob, Louis Reigel, assistant director of the FBI's Cyber Division told reporters. While Ancheta operated as a sole proprietor, and Maxwell was part of a three-man shop, Essebar and Ekici functioned more like freelancers, says Allor. They appeared to be part of a loose "confederation of folks who have unique abilities," says Allor. "They come together with others who have unique abilities, and from time to time they switch off who they work with." Despite their notoriety, Essebar, Ancheta and Maxwell represent mere flickers in the Internet underworld. More elite hackers collaborating with organized crime groups take pains to cover their tracks — and rarely get caught. "Those toward the lower levels of this strata are the ones that tend to get noticed and arrested pretty quickly," says Martin Overton, a security specialist at IBM. Acohido reported from Seattle, Swartz from San Francisco. For more educational resources, visit http://education.usatoday.com Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page Page 7 8 AS SEEN IN USA TODAY’S MONEY SECTION, APRIL 24, 2006 Cybercrime, Inc. Some ‘script kiddies’ get more attention than others By Jon Swartz and Byron Acohido USA TODAY based PCs to crash and reboot, was sentenced to 21 months of probation. SAN FRANCISCO — It used to be that kids collected comic books and baseball cards. In the digital age, some youngsters amuse themselves by seeing how many Internet-connected computers they can infect for fun or profit. He received only 30 hours of community service and was later hired as a consultant at a computer-security company, Securepoint, in Germany. Known as "script kiddies," these young people typically have no formal training. But they are comfortable at a keyboard and adept at self-learning. Noodling at their computers while munching on junk food, they search out and tweak malicious computer code, called scripts, created by others, according to computer-security experts and law enforcement officials involved in the prosecution of teenage hackers. Instead of riding bikes or playing ball, script kiddies immerse themselves in a digital world steeped in an ethic that holds all things in cyberspace to be fair game for clever manipulation. Most seek kudos from peers who admire those who can infect the most PCs. But from there it's a small step to rationalize using hacking skills to make a quick buck. "We talk about safe sex, avoiding drugs and alcohol. But we don't talk about computer ethics," says Paul Luehr, a former federal computer-crimes prosecutor. Script kiddies who rose above their peers to earn wider infamy include: u Kim Vanvaeck, 19 when arrested in 2004. The Belgian female, author of a computer virus that scrambled MP3 files and caused quotes from TV's Buffy the Vampire Slayer to pop up on PC screens, was arrested outside Brussels and charged with computer data sabotage. The case was dropped. Vanvaeck began tweaking viruses at 14 but maintained she never actually released any of her creations on the Web. "When people make guns, can you blame them when somebody else kills with them?" she told TechTV.com in a 2002 interview. "I only write them. I don't release them." u Sven Jaschan, 17 when arrested in 2004. The German author of the Sasser worm, which caused millions of Windows- Jaschan started writing computer viruses in early 2004 after he learned about the MyDoom e-mail virus and how it had infected millions of Windows-based PCs. Working in the basement with his stepfather, a PC repairman, the precocious Jaschan wrote the Netsky e-mail virus, which cleaned up MyDoom infections but was itself invasive, according to a 2004 interview Jaschan did with Germany's Stern magazine. Jaschan progressed to creating the destructive Sasser worm, which spread much faster than Netsky because it required no action by the PC user. u Jeffrey Lee "Teekid" Parson, 18 when arrested in 2003. A high school senior from Hopkins, Minn., Parson was one of many copycat hackers who tweaked the invasive MSBlaster worm in 2003. His version infected 48,000 PCs and caused $1.2 million in damage, prosecutors said. But Parson failed to cover his tracks well. A link in his coding pointed to a website where he stored other viruses alongside lyrics to his favorite songs by Judas Priest and Megadeth. U.S. District Judge Marsha Pechman, who sentenced Parson in January 2005, said Parson was a lonely teenager who holed up in his room and created his "own reality." Parson is currently serving an 18-month sentence in Duluth (Minn.) Federal Prison Camp. His projected release is Aug. 14. His attorney, Nancy Tenney, describes him as shy and said he declined an interview. Parson was the only hacker arrested in connection with MSBlaster, which infected more than 20 million PCs. Swartz reported from San Francisco, Acohido from Seattle. Reprinted with permission. All rights reser ved. Page 9 Discussion u Why does Microsoft collect and aggregate data about its customers? How do Internet companies use this information to target consumers? Why do these data collection techniques have some privacy advocates worried? How do you feel about the practice? u What is data mining? How do companies use it to learn more about consumers, increase profits and improve their businesses? Describe an example of a sophisticated data mining model. What problems has the growth in data mining created? u Why are college students popular victims of identity theft? How do college students put themselves at risk? Why is it unwise to post too much personal information on open, social-networking websites, such as MySpace or Facebook? u What is a computer “bot”? What are they capable of doing? How do bot herders partner with organized crime groups? What is their goal? u Why is it imperative for adolescents and their parents to communicate openly about the potential dangers of the Internet (in addition to its benefits)? What software is available to help you protect yourself from potential identity thieves and other online predators? Activity Phishing is an online identity theft scam that tricks a person into giving out confidential details, such as his or her Social Security number or credit card account information. It is derived from the word fish, because these predators are said to “bait” and “hook” potential victims. Based on the information in this case study and other articles in current editions of USA TODAY, list 10 techniques (e.g., spam filtering, vigilance, etc.) that people can use to protect their personal information and their personal safety online. Explain how each strategy works and why it is important. Additional Resources q Identity Theft Resource Center (www.idtheftcenter.org) Helps people prevent and recover from identity theft. The site also provides information for victims, details on current laws, media resources and a reference library. q Privacy Rights Clearinghouse (www.privacyrights.org) A non-profit consumer information and advocacy organization that supplies information on identity theft, fraud prevention and online privacy. © Copyright 2006 USA TODAY, a division of Gannett Co., Inc. All rights reser ved. Page 10