Refining rabbit care

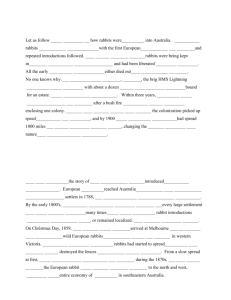

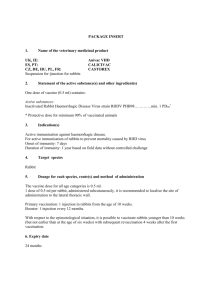

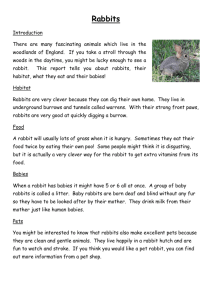

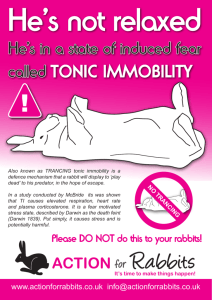

advertisement