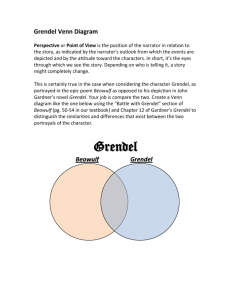

Grendel as a Monster: The Monstrosity of John Gardner's

advertisement