Cultural Knowledge and Social Inequality

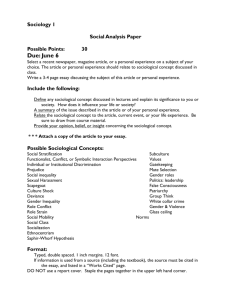

advertisement