the foreign policy of Taft and Wilson

advertisement

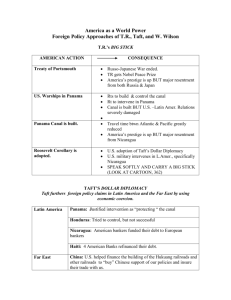

Taft’s and Wilson’s diplomacy The Diplomacy of Taft and Wilson William Howard Taft’s presidency had a slightly different approach to diplomacy. He planned on “substituting dollars for bullets.” Taft pointed out that America’s foreign investments had increased from $800 million in 1898 to more than $2.5 billion in 1909. In the Caribbean, Taft worried that the European powers might create a threat to American power should Latin American nations default on their debts (to default on a loan is to refuse to pay the loan off). Taft worked to replace European loans with American loans. American bankers assumed the debts of Honduras and invested in Haiti to make sure that Europe did not interfere. When the government of Nicaragua refused to pay off their debts to Britain by taking out American loans, the president dispatched a warship to the area and used political pressure to make the Nicaraguan government pay up. The Senate also worked to protect American interests by warning other nations that their companies were not to invest heavily in Latin America or Mexico. When Woodrow Wilson entered the presidency he knew little about foreign policy. He believed that democracy was the best opportunity for stability and order in the world. He promised to use a foreign policy based on moral values. Wilson scrapped dollar diplomacy in Asia. Wilson wanted to make sure that China was no longer exploited by Russia and Japan. Unfortunately, revolution in China prevented him from taking his stand against the Japanese and Russian governments dominating China. In fact, the start of World War I in 1914 turned Russian attention away from its eastern borders and toward Europe. Japan seized German holdings and would have taken more of China if the British and the Chinese people had not stopped them. In Latin America Wilson promised to focus on “human rights” and “national integrity.” However, when the Dominican Republic threatened to default on its loans, Wilson sent in the marines. The following year the US ended up in Cuba to protect American investments from attacks by Cubans. When Haiti’s central bank became controlled by New York bankers, the US took a new interest in that country. When an uprising threatened the security of the country, Wilson sent in the marines and negotiated a treaty in 1915 that granted the US control over the country’s foreign and financial affairs as well as the right to intervene whenever the US thought it was a good idea. The marines stayed in Haiti for 19 years. In Mexico, Wilson saw a chance to play out his moral foreign policy. In 1913 General Victoriano Huerta gained control of Mexico’s government and murdered Francisco Madero, a reformer who had come to power in 1911. Wilson refused to recognize the new power. American businesses begged the president to recognize the new government so that trade could resume. Wilson demanded elections. He saw an opportunity to step in when Huerta’s agents arrested seven US sailors who, while on shore, had strayed beyond their designated area. Huerta apologized and released the prisoners, but refused to issue a 21-gun salute to the American flag to satisfy American honor. Wilson asked Congress for permission to use American troops to force Huerta to recognize American “rights and dignity.” 1 Taft’s and Wilson’s diplomacy While Congress debated, Wilson learned that a German arms shipment for Huerta’s military planned to unload at Vera Cruz. Wilson ordered the navy to land troops and occupy the port. Fighting broke out in May that killed 19 Americans and over 126 Mexicans. Wilson intended to overthrow Huerta. Instead he offended most Mexicans, and had to accept outside interference from Latin American nations to negotiate a settlement. Meanwhile, Huerta and Venustiano Carranza, the “constitutionalist” leader who Wilson supported, continued to struggle for power. During that summer, Carranza’s forces drove Huerta from power. Much to Wilson’s surprise, Carranza announced plans for land reform that would threaten US holdings and claimed the rights to all Mexican oil, which greatly disturbed American oil companies. Wilson turned against Carranza and threw his support behind Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Wilson saw Villa as a Robin Hood style figure. However, Carranza’s forces were too strong for Villa. In 1915 Wilson abandoned his ideas for moral diplomacy in Mexico and recognized Carranza’s government. Villa was not pleased. He responded to this withdrawal of support by terrorizing Americans, hoping to force Wilson into a retaliation that might topple Carranza’s government. In March of 1916 he led a force of fifteen hundred revolutionaries across the border to burn the town of Columbus, New Mexico. This attack left seventeen Americans and more than one hundred Mexicans dead. Outraged by the attack, Wilson sent General John J. Pershing after Villa to capture him and bring him to the United States for trial. Villa and his men constantly eluded capture. Pershing expanded his army to more than 11,600 men and moved more than 300 miles into Mexico. Carranza, annoyed by this military advance into his country, ordered Pershing to stop his advance. American troops clashed with Carranza’s forces, resulting in the death of twelve Americans and the capture of twenty-four more. This brought the countries to the brink of war. Carranza released the prisoners but demanded that Wilson withdraw American troops from Mexico. Wilson, facing reelection, would not withdraw his troops. However, once he won the election of 1916, and with the prospect of war in Europe, he ordered withdrawal of all troops in January of 1917. Entry into World War I: War broke out in Europe in the summer of 1914. The United States pledged to remain neutral. One of the great challenges to neutrality was the German Navy's submarine warfare. Many Americans, and Wilson in particular, regarded the sinking of defenseless merchant ships from beneath the waves as unfair and a violation of the rules of war, to say nothing of the rules governing the civilized behavior of human beings in general. The question was not merely one of interference with free trade, but, as with many of Wilson's positions, a moral issue. It was the use of submarines that would eventually bring the United States into the war, and in his request to Congress for a declaration of war in 1917, Wilson described the actions of German submarines as “warfare against mankind.” 2 Taft’s and Wilson’s diplomacy Germany's actions strengthened Wilson's private conviction that the struggle in Europe was between the forces of democracy and those of authoritarianism. While Wilson was worried about British and French imperialism, he saw German Kaiser Wilhelm II as the greatest threat. Thus, Wilson blocked an attempt by Congress to end the shipment of arms to Europe that was intended to enforce more strictly the spirit and letter of neutrality. In 1915, he also canceled a measure forbidding loans to belligerents, opening up America's financial resources to the Allied Powers. Still, the United States did not immediately enter the war, despite damage caused by the German submarines. On May 7, 1915, a torpedo struck the British passenger liner Lusitania, killing 128 Americans and prompting a strong U.S. protest. In response, the German government promised to give warning to passenger ships before firing on them. This protocol of giving warning before a submarine attack was one of Wilson's main demands, calculated in the president's mind to render the actions of submarines less unfair. However, surfacing to warn targets eliminated the submarine's most effective characteristics—stealth and surprise—and exposed it to enemy battleships. Nonetheless, the Germans scaled back their effort, hoping to avoid direct American intervention on the side of the Allies. By January 1917, the German High Command decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare, believing that Germany could win the war against the exhausted Allies before the United States could bring its full force to bear in the conflict. During the next two months, the German Navy sunk several American merchant vessels, and Wilson broke off all diplomatic relations with Germany. Still, he hoped to keep the United States out of the war. In late February, the British government revealed that they had intercepted a telegram from German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann to the German ambassador in Mexico. The socalled Zimmermann Note proposed a German-Mexican alliance against the United States and promised the return of former Mexican territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. When word of the telegram leaked out in the United States, the American public turned decisively against Germany. After the Germans sunk several more American ships in the following weeks, Wilson finally asked for a declaration of war. Sources: Gillon, Steven M, and Matson, Cathy D.. The American Experiment, A History of the United States: Volume II. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002. http://www.americanhistory.abc-clio.com/library/searches/searchdisplay.aspx?entryid=263294&fulltext=World+War+I&nav=non http://www.americanhistory.abc-clio.com/library/searches/searchdisplay.aspx?entryid=253888&fulltext=anti-imperialist+league&nav=non 3