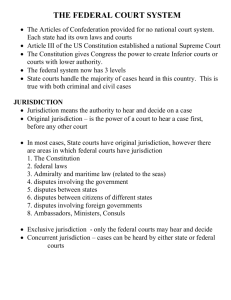

Federalists, Federalism, and Federal Jurisdiction

advertisement