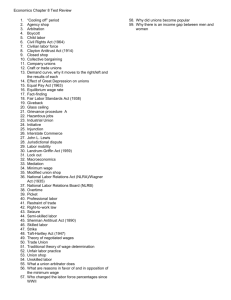

Beyond Unions, Notwithstanding Labor Law

advertisement