To what extent did the religious beliefs of the American

advertisement

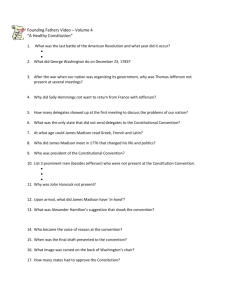

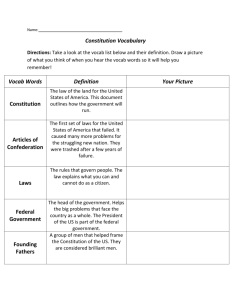

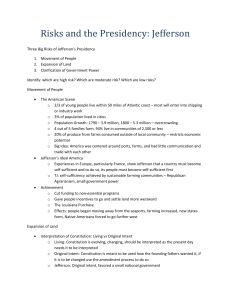

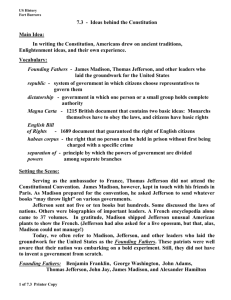

To what extent did the religious beliefs of the American founding fathers influence their decisions in writing the U.S. Constitution? Peter Potash IB Candidate Number: 001035 0046 History Rubric West Morris Mendham High School Word Count: 3,818 Abstract Since the end of the Constitutional Convention, historians and politicians have debated the influence of the religious beliefs of the founding fathers on the drafting of the U.S. Constitution. Some believe that the founders’ goal of separation of church and state prevented the existence of any religious influence in the Constitution; others argue that the Constitution can be considered a Christian document because the Christian beliefs of the Framers had such a great effect on the decision-making process. Among all of these modern arguments, the voices of the original delegates often are lost. This investigation aims to analyze the original intentions of the founding fathers in regards to how they allowed their religion to influence the new government set forth in the Constitution. This investigation was conducted through a variety of primary and secondary sources. Many primary sources from the Constitutional Era reflect the religious beliefs of the founders at the time and how those beliefs played a role in the new government. Some primary sources include The U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights, the Federalist Papers, and Washington’s Farewell Address. Secondary sources gave further information on the beliefs of the founders and the connections between government and religion. A Stanford University database was utilized to find connections between Christianity and morality while PBS.org’s series God in America yielded informative research on how the founding fathers applied religion to government. This research led to the conclusion that the religion of the framers undoubtedly had an effect on the content of the Constitution but not to the point where it can be considered a Christian document. Aspects of Christianity like sin and morality influenced the new laws, but the need to separate church from state in order to purify religion prevented the Constitution from classification as a Christian document. Word Count: 298 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 4 The Founding Fathers and Religion……….………………………………………………………………….. 4 James Madison …………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Thomas Jefferson…………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 George Washington……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Religion, Morality, and Government…………………………………………………………………………. 9 Religion and the Constitution…………………………………………………………………………………….. 10 The First Amendment……………………………………………………………………………………. 10 Arguments for Christian Influence………………………………………………………………… 12 Separation of Church and State……………………………………………………………………. 12 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 16 3 To what extent did the religious beliefs of the American founding fathers influence their decisions in writing the U.S. Constitution? Introduction: In the Philadelphia statehouse in 1787 delegates from the newly-independent United States of America convened to form a new government. The result of their deliberations, the U.S. Constitution, continues to govern the American people to this day. Naturally, many a debate has argued the true intent of the founding fathers. One of the most contested aspects of the Constitution involves the framers’ interpretations on religion and its purpose in the federal government. The authors of the Constitution were for the most part deeply religious men yet the Constitution seems to construct a completely secular government; this phenomenon has come to be known as “separation of church and state.” Other contemporaries argue that the religious opinions of the forefathers made it impossible for them to completely separate the church from the state. I aim to settle the debate through an analysis of the religious backgrounds of prominent forefathers, connections between the entities of government and religion, and specific references within the Constitution concerning religion. Through this analysis, I conclude that the religious beliefs of the founders influenced the Constitution to a large extent yet did not categorize it as a Christian document. The Founding Fathers and Religion: In order to analyze the effect of the religious beliefs of the founding fathers we must first understand the nature of their beliefs. The Framers were white, middle-to-upper class citizens and were therefore fairly wealthy. They were quite alike in their religious beliefs; the overwhelming majority of the 55 delegates were Protestant. The largest sect of Protestantism among the delegates was Episcopalian or Anglican; approximately 54% of the delegates practiced that religion (Ferris 138). 4 Presbyterian followed in second with about 29% of the delegates, and other sects included Congregationalist, Methodist, and Lutheran ( 138). Two of the more diverse religions of the delegates were Catholicism and Quaker; two delegates represented each of these denominations (“The Charters of Freedom” Archives.gov).These statistics though reflect an overwhelming majority of Protestantism among the delegates; therefore this essay primarily analyzes Christianity and its connections to the framers and the Constitution. Religions such as Islam, Judaism, or Atheism which are fairly common today had not yet surfaced in 18th Century American politics. Influences of an author tend to translate to his/her writing; therefore, it is entirely possible that the Christian religions of the founding fathers affected their draft of the U.S. Constitution. James Madison Insight on the religious backgrounds of the most prominent delegates to the Constitutional Convention is vital in this investigation, and no delegate was as prominent as the “Father of the Constitution,” James Madison. He “was a close student of theology” and “was undoubtedly well-versed in the political implications of American religious thought” (Lutz, Warren 83). Madison’s religious beliefs were nurtured throughout his adolescence at both boarding school and college. At the College of New Jersey, later known as Princeton, Madison studied under Dr. John Witherspoon who taught “law, politics, ethics, and philosophy from a Christian perspective” (Sheldon 89). Throughout his life, Madison dealt with secular problems by applying his Christian perspective to the issue. The Constitution is a prime example in which Madison applied his religious views to his political philosophy. Madison took the Calvinist approach that all men have a nature for sin and evil. Madison saw that in the political world, this evil takes “the form of lust for power, control, domination, and oppression of others” (Sheldon 90). His solution to safeguard the country from this inherent evil of mankind was the system of checks and balances. In his Federalist Paper No. 10 Madison explains, “Extend the sphere and… you make it less probable that a majority of the whole will have a common 5 motive to invade the rights of other citizens.” By creating checks and balances, Madison prevented one person from executing his sinful human nature at the expense of the American public. He spread the power of the government over three branches so that numerous people can step in before a single man’s power can dominate the political landscape in autocratic fashion. Many historians do not associate Madison with orthodox Christianity and instead classify him as a Deist. Deism was a “liberal strain of Christianity that stressed reason and free inquiry over revelation” (“God and the Constitution”). In other words, both Christians and Deists believed in God as a Creator, but Deists limit some of the more fantastical aspect of the Christian religion due to their belief in logic and reason. Due to Madison’s quest for reason, he was not swept up in the corruptions of the Anglican Church; when he returned from university, he was “outraged to discover that a number of Baptist preachers had been thrown into a Virginia jail” because they had been preaching a slightly different sect of Christianity (“People & Ideas: James Madison”). Madison saw the illogicality of this religious persecution and also drew parallels to the dominant yet corrupt Anglican Church in England. These factors both influenced his decision to include the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” in his Bill of Rights (qtd. in Robinson). Madison instead aimed to establish a place where the Gospel could be spread through all sects of Protestantism instead of through just the Anglican Church; he aimed to promote Christian evangelism (Sheldon 97). Madison’s adversity to the emotional wave produced by the Anglican Church led him to the First Amendment which allowed for a greater evangelistic environment in America. Madison’s religious beliefs, or in this case his skepticism, directly influenced his ideas for the Constitution. Thomas Jefferson Madison’s idea of the right to religious freedom originated with Thomas Jefferson’s ideas for Virginia’s state government. Jefferson had also noticed the problem of the dominating and intolerant 6 Virginian Anglicans, so he penned the “Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom in Virginia” in 1777 to solve the dilemma. The document states, “All men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion in matters of religion, and that shall in no ways…affect their civil capacities.” Jefferson ensured the freedom of religion and prevented one’s religion from negatively affecting one’s social standing. Jefferson’s passion for freedom of religion differed from that of Madison though. Jefferson’s views on religion were “rooted in his conviction that all human beings had been endowed by God with certain rights” (Fea 210). Jefferson’s views on rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” are stated in his Declaration of Independence, and freedom of religion was simply another natural right he added to his personal list. Although Jefferson was not present at the Constitutional Convention, he was quite an influential political figure of the era. Jefferson took an interesting approach to religion; he was raised an orthodox Anglican but transformed into a skeptical follower of Jesus. The Enlightenment and Deism greatly influenced Jefferson, and the reason and logic behind these movements led Jefferson to reject “standard Christian doctrines like the Trinity and the divinity of Christ” (Buckley 56). Although Jefferson denied the logic of the faith-based aspects of Christianity, he still called himself a Christian because he attempted to follow the moral code Jesus set. Jefferson called Jesus’ teachings and morals “the most perfect and sublime that has ever been taught by man” (Fea 205). He translated Jesus’ principles to politics by finding a “need to establish the republic on a foundation of high moral principles” (Lutz 84). Due to his religious skepticism, it may appear as if his religion had no effect whatsoever, but in fact, his following of Jesus led Jefferson to establish a government based on Biblical morality. George Washington George Washington also articulated his religious beliefs by way of the role of morality in the federal government. Although renowned for his military skills, Washington’s political opinions were also well-respected, especially as Chairman of the Constitutional Convention. When Madison presented his 7 freedom of religion clause in the Bill of Rights, Washington made a counter-argument. Washington encouraged support of a single, Christian religion because he believed “government should support religion because religion supports republican government” (Munoz 10). In other words, Washington believed religion through its moral compass was beneficial to the institution of republicanism because it would help to maintain the peace in society. Washington’s foresight warned him of the potential of a religion hostile to the maintenance of peace at some point in the future. Ultimately, the delegates accepted Madison’s idea, but Washington certainly provided a valid point for debate. Washington’s religion was also uncertain; he was very private about his religious studies. Washington practiced private prayer and believed in a “Creator God...who was also active in the universe” (Tsakiridis). Some called him a Deist for his unwillingness to publicly profess his religion, but his beliefs in an active Providence align more with orthodoxy than traditional Deism (Tsakiridis). Nonetheless, Washington seemed to have appreciated religion more as a tool to help enrich and govern the public. In his famous Farewell Address of 1796, Washington claimed “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports.” Washington established the symbiotic relationship of government with religion and morality. Without them, government could not prosper to the same extent. Washington’s Farewell Address is a particularly useful source for this investigation as it combines the advantages of primary and secondary sources in one document. Primary sources are often advantageous because the information reflects the ideas of the author in the specific historical moment. Although Washington wrote his Farewell Address a decade after the Constitutional Convention, he was still present at the Convention and knew of the original opinions of the delegates. Primary sources falter though because often they do not have the benefit of analyzing how their ideas work in society. For example, Madison’s Federalist Paper 10 was an idealistic application of his religion to reality; there was no guarantee the system of checks and balances would succeed. Washington’s account had the 8 advantage of analyzing the first implementations of the new government which led him to a conclusion of the significance of religion in government. Washington’s knowledge of the Constitutional Convention linked with his ability to analyze the results of the Convention make his Farewell Address a highly reliable and useful source. Religion, Morality, and Government Washington and Jefferson both refer to Christianity, specifically its morality, as a foundation for government. Neither man though is quite specific on how Christianity connects to this morality or how these connect to the Constitution. John Hare recently published a work called “Religion and Morality” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy that explores the connection between the two subjects. He includes a large section on religion and morality in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, and Hare ultimately concludes that “morality and religion are connected in the Hebrew Bible primarily by the category of God’s command.” I agree wholeheartedly with this statement; God creates right and wrong through the commands he makes. In Genesis, God tells Adam and Eve they can eat from any tree of the Garden of Eden except for the tree of knowledge of good and evil. When they disobey his commands they are morally wrong. In Exodus 20, God gives the Ten Commandments to the Israelites to show them right and wrong. God establishes murder, adultery, theft, and lies to be morally wrong; these are often punishable in the courts of law in modern society as well. Jesus continues these commandments in the New Testament when he commands to love the enemy and the neighbor as thyself (Matthew 5:43-48). This compares to society in that those who work together and overcome differences often result in a more functional society. These biblical connections in which God’s commandments shape morality are often reflected in the moral code of society today. How then can this connect to the Constitution and its Framers? The Constitution is considered to be the “law of the land”; its main function was to establish the existing government, but it also must 9 maintain that government. The Founders realized that in order to live in a free society with a limited government that the Constitution provides, “each citizen must be able to control himself” or else there would be a need for a police state and a highly-involved government (“George Washington and Religious Liberty”). The Founders and the Americans had just emerged from the repressive tyranny of the British rule which certainly violated many of these religious moral codes. The Americans most likely wanted a new government in which both the citizens and government practiced an upstanding moral code which would naturally result in a healthy relationship between state and citizen. When establishing this moral code, the Founders drew on the Christian morality with which they had been raised. The Framers established laws to encourage actions considered morally right and discouraged actions morally wrong. Through this system of governance, the founding fathers bred civic morality based off of the religious moral doctrines. Religion and the Constitution Much of the debate over the extent to which the founding fathers’ religions influenced the Constitution lies within the semantics of the Constitution itself. Some believe the influence was so great that the Constitution should be considered a Christian document; others believe there is a complete void of any Christian influence within the document. Both reference specific examples throughout the body of the document to support their respective cases. The First Amendment One of the most controversial topics in this debate is the First Amendment which states that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.” Those that argue that the forefathers did not include their Christian beliefs in the Constitution point to this amendment as their main evidence. The amendment explicitly states that the government cannot establish an official religion that is deemed better than others. It is argued that if the forefathers had let their beliefs 10 interfere with the Constitution, they would have established an official religion of Protestantism. Instead, they made a decision for the people who were different from them and established a nation based on equality and freedom. This is the traditional view of a historian that argues the Convention was successful in separating church and state and forming a completely secular government. In contrast, the opposing side argues that the First Amendment is based off of ideas from Jefferson’s statute on Freedom of Religion in that freedom of religion existed under the banner of Christianity. These historians show historical empathy by noticing that the founding fathers really did not consider Muslims or even Jews because those religions were not yet prevalent in the fledgling country. Instead, the founding fathers considered the different conflicting sects of Christianity such as Quaker, Mennonite, Catholic, Episcopal, Anglican, Presbyterian, and so on. Dr. Dave Miller of Apolgetic.org argues this point in support of a Christian influence by citing George Mason’s original copy of the First Amendment that states “no particular sect or society of Christians ought to be favored.” It must be taken into consideration that Miller’s argument is highly biased towards a pro-Christian side, but the primary source does substantiate the freedom to practice different sects of Christianity. In reality, both sides fail to see the true meaning of the First Amendment outlined by James Madison. As discussed earlier in the essay, Madison made the First Amendment to prevent the Anglican Church from persecuting its fellow Protestant sects. He did not suggest it with secular implications; Madison in fact hoped to provoke evangelism by giving all sects of Christianity the freedom to spread the Gospel. On the other hand, the semantics of the First Amendment leaves the right open to all Americans, so the amendment is not restricted to Christian freedom either. The Framers had the foresight for the possibility of new and different religions, and today, with the mixed landscape of religious practices in the United States, the First Amendment applies to all religions. The original intentions of the First Amendment were anything but secular, and the development of new religions has prevented it from applying to strictly Christians. 11 Arguments for Christian Influence In Article 1 Section 7 of the Constitution, there is a clause that gives Congress a time limit of 10 days to present a bill to the President, but Sundays are exempted (Miller). Proponents of a Christian influence claim that the founding fathers excluded Sundays for religious purposes while dissenters argue the clause’s insignificance. The clause really is insignificant and does not show excessive religious influence on the part of the founders. After all, in modern times, many businesses without religious affiliations take off for the weekend, the traditional days of worship. Another interesting reference involves the date on the Constitution. The date says “in the 1787 year of our Lord.” Some argue that this reference to a supreme being must mean that the Christianity of the forefathers influenced the Constitution. The reality is that all official dates were completed in this manner on all important documents in that time period. It was exactly like writing 12/20/13 in present times. Neither of these arguments are sound and definitive examples that show the influence of the founding fathers’ religions on their writing of the Constitution. Separation of Church and State A main argument for the side that opposes Christian influence is that there is not one mention of Jesus Christ or Christianity in the whole Constitution. If the Constitution was influenced by Christianity, one would think the religion or the figurehead of the religion would be alluded to multiple times. The fact that the founding fathers did not allude to Christianity shows that they focused on a government completely separated from the church. The counterargument would be that some of the Christian influences are implied and are indeed heavily present yet not out rightly stated. Those that argue against Christian influence tend to utilize the phrase “separation of church from state” or “wall of separation” to articulate their opinions. Many do not realize the phrase did not originate until Thomas Jefferson’s 1802 letter to a group of Connecticut Baptists. The Baptists had 12 written to Jefferson about the oppressive Congregationalist Church oppressing the rights of the Baptists to worship, and Jefferson responded with the following: “Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God,, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate … that their legislature should “make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,” thus building a wall of separation between Church & State” (qtd. in “People and Ideas: Wall of Separation”). It can be seen that Jefferson was encouraging the practice of religion and discouraging the role of a dominant, politicalized church. Jefferson is reminiscent of Roger Williams who compared the church to a garden that must be protected from the wilderness of the world (“Wall of Separation”). In essence, Jefferson aimed to protect the purity and fragility of religion from the corrupt world of politics. In modern times, the phrase “wall of separation” is often used by anti-religionists to suppress religion from influencing the nation’s perspective when a contentious religious point circulates the political realm. This modern interpretation clearly strays far from that of Jefferson’s use of it to promote the spread of religion. Conclusions The religious beliefs of the framers influenced the formation of the new government laid out in the Constitution to a great extent. Madison’s religious belief of the inherent sinful nature of humans influenced his decision to protect the country from the possibly errant decisions of a singular leader. Washington established the importance of Christian morality to the success of the government. Jefferson too, influenced by the teachings of Jesus Christ, aimed to adhere to the Christian moral compass through the laws and governance of the new country. Even the Deist beliefs allowed Madison and Jefferson to see through the corruption of the established Anglican Church and promote religious 13 freedom for all sects of Christianity and any other future religions. Each of these examples depicts a clear instance when the religious beliefs of a founder directly affected their ideas which were then used to create the U.S. Constitution. If the founding fathers’ Christian religions had such an influence on the Constitution, wouldn’t the next logical step be to declare the document a Christian document? No, the Constitution was in no way a Christian document. Many experts would agree with me; John Fea states, “The Constitution was never meant to be a religious document, nor did its framers set out to use the document to establish a Christian nation” (150). My conclusion comes from the simple fact that, as one source states, “God and Christianity are nowhere to be found in the American Constitution” (Kramnick, Moore 130). Unlike the Declaration of Independence which references the “Creator”, the U.S. Constitution never mentions God or Jesus. The purpose of the Constitution was to establish a functional government. The founders applied their belief systems, including their Christian beliefs, in order to search for a solution, but the end goal was to establish a governmental system not a religious one. The principal reason the founding fathers did not mold their religious beliefs into a Christian document was indeed their intent to separate church from state. The phrase has developed into a hostile statement utilized by anti-religionists whenever a religious issue arises in the political world. The original purpose of the separation was to promote religion instead as compared to the more suppressive modern interpretation. The founders viewed religion as a sanctified, pure, and holy entity that must be untouched by the filthy corruption of government. Examples from the English Anglican Church and even the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages show how the sanctity of religion is easily marred by the political machine. In essence, the purity of the founders’ Christianity had a positive and natural effect in their deliberations to find a functional government, but the founders made a concerted effort to separate the corruption of politics from the purity of religion. 14 Religious influence at the Constitutional Convention has become quite a contentious point over the centuries since 1787. As new arguments begin to surface from diverse points of view, the original intentions and beliefs of the founding fathers begin to fade away. The debate has pitted atheists who deny any religious influence in the Constitution against radical Christians who claim the Constitution is a Christian document. Neither of these sides is correct because they both fail to truly analyze the actions and intentions of the founding fathers. My purpose was to find this original intent through primary sources and other historians’ analyses and settle the debate from my research-based perspective. The Framers of the Constitution hold the real answers to this debate as opposed to the skewed opinions of current debaters. Word Count: 3,818 15 Bibliography Banyan, Margaret E. “Civic Virtue.” Britannica.com.Encyclopedia Britannica 2014. Web. 29 Aug 2014 Buckley, Thomas E. “The Religious Rhetoric of Thomas Jefferson.” The Founders on God And Government. Ed. Daniel L. Dreisbach, Mark D. Hall, and Jeffry H. Morrison. Lanham,MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2004 53-82. Print. Fea, John. Was America Founded as a Christian Nation? Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press 2011. Print. Ferris, Robert G. Signers of the Constitution: Historic Places Commemorating the Signing of The Constitution. United States Department of the Interior Park Service, 1976. Washington D.C. Web. 20 Dec 2014 “George Washington and Religious Liberty” Rediscovering George Washington. PBS.org. The Claremont Institute, 2002. Web. 21 Dec. 2014 “God and the Constitution” God in America. PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation 11 Oct. 2010. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. Hare, John, "Religion and Morality" The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Web. 21 Dec. 2014. Kramnick, Isaac, and R. Laurence Moore. “The Godless Constitution.” Protestantism and the American Founding. Ed. Thomas S. Engeman and Michael P. Zuckert. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame 2004. 129-142. Print. Lutz, Donald S. and Jack D. Warren. A Covenanted People:The Religious Tradition and the Origins of American Constitutionalism. Providence, RI: John Carter Brown Library 1987. Print. 16 Madison, James. “Federalist Paper #10.” Daily Advertiser 22 Nov. 1787 ed. John Roland Constitution Society. Web. 18 Aug. 2014 Miller, Dave. “Christianity is in the Constitution.” ApologeticsPress.org. Apologetics Press Inc. 2008. Web. 29 Aug. 2014 “Morality.” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. n.p. n.d. Web. 29 Aug. 2014. Muñoz, Vincent Phillip. “Religion and the Common Good.” The Founders on God and Government. Ed. Daniel L. Dreisbach, Mark D. Hall, and Jeffry H. Morrison. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2004. 1-22. Print. “People & Ideas: James Madison.” God in America. PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation 11 Oct. 2010. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. “People & Ideas: Thomas Jefferson.” God in America. PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation 11 Oct. 2010. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. “People & Ideas: Wall of Separation.” God in America. PBS.org. WGBH Educational Foundation 11 Oct. 2010. Web. 21 Dec. 2014. “Religious Affiliation of the Delegates to the Constitutional Convention of 1787.” Adherents. com. n.p. 4 November 2005. Web. 28 Aug 2014. Robinson, B.A. “The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Religious Aspects.” Religious Tolerance.org. Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance. 13 July 2013. Web. 28 Aug. 2014. Sheldon, Garret Ward. “Religion and Politics in the Thought of James Madison.” The Founders On God and Government. Ed. Daniel L. Dreisbach, Mark D. Hall, and Jeffry H.Morrison. Lanham,MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2004. 83-115. Print. 17 Tsakiridis, George. “George Washington and Religion.” MountVernon.org. Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. 2014. Web. 20 Dec 2014 Washington, George. “The Farewell Address.” 1796. MS. Lib. Of Congress Washington D.C. Lib of Cong. Web. 15 Dec 2014. 18