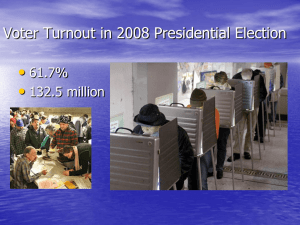

Who Votes? Voter Turnout in New York City

advertisement