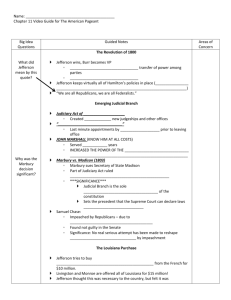

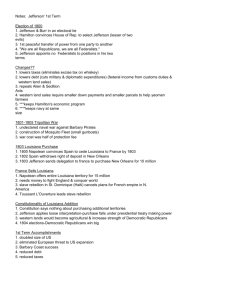

aaron burr and the electoral tie of 1801: strict constitutional

advertisement