Outing2010

Age

PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES AFFECTING LESBIAN,

GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ELDERS

BY JAIME M. GRANT

NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE

WITH GERARD KOSKOVICH, M. SOMJEN FRAZER, SUNNY BJERK,

AND LEAD COLLABORATOR, SERVICES & ADVOCACY FOR GLBT ELDERS (SAGE)

Outing2010

Age

PUBLIC POLICY ISSUES AFFECTING LESBIAN,

GAY, BISEXUAL AND TRANSGENDER ELDERS

BY JAIME M. GRANT

NATIONAL GAY AND LESBIAN TASK FORCE POLICY INSTITUTE

WITH GERARD KOSKOVICH, M. SOMJEN FRAZER, SUNNY BJERK,

AND LEAD COLLABORATOR, SERVICES & ADVOCACY FOR GLBT ELDERS (SAGE)

OUTING AGE 2010

Acknowledgements

T

he Task Force is grateful for the generous support of the Arcus

Foundation, which funded the research, development and publication of

Outing Age 2010. AARP also provided critical support for this research.

This book has been years in the making and has required the careful attention of

many talented researchers and advocates. The Task Force greatly appreciates

the vision and dedication of Amber Hollibaugh who, in her time as Senior

Strategist on Aging at the Task Force, created a national network of advocates

and pioneered many of the perspectives and positions herein.

We want to thank Task Force interns and fellows who made important

contributions to this volume: Ernest Gonzales, Carla Herbitter, Erika Grace

Nelson, Tey Meadow, Patrick Paschall, Angie Gambone, Jesse Zatloff, Meredith

Palmer and also former Senior Policy Analyst Nicholas Ray.

Several experts in LGBT aging helped refine our drafts and hone our perspectives:

Dr. Kimberly Acquaviva, Loree Cook-Daniels, and Dr. Brian DeVries.

At the Task Force, our resident expert on Aging, Dr. Laurie Young, made

essential contributions to the book. Thank you, Laurie, for your patience,

guidance and above all, good humor. Staffers Amy Sagalkin and Darlene Nipper

made extremely helpful editorial comments.

The intrepid Karen Taylor at SAGE in New York kept us on task and gave critical

support, comments and feedback throughout. SAGE has served as a lead

collaborator on this project, and their contribution has been invaluable.

Task Force Vaid fellow Jack Harrison performed the “heavy lifting” on fact and

reference checking and the book’s appendices. He made it possible to get our

final draft across the finish line.

Finally, the shape of this book owes much to its predecessor, Outing Age, and the

sharp thinking of its authors, Sean Cahill, Ken South and Dean Spade. Thanks for

setting such a high bar in research and advocacy for LGBT elders. Your work has

had an enormous impact on the field and the movement as a whole.

1

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Table of Contents

Foreword by Rea Carey ............................................................................................................................... 4

Executive Summary and Recommendations ................................................................................ 7

Why This Book?.............................................................................................................................................. 13

Who Are Elders in America in General?......................................................................................... 19

What Do We Know About LGBT Elders?....................................................................................... 24

How Many LGBT Elders Are There? ........................................................................................... 26

Class, Race and Gender in Aging ................................................................................................ 26

The Diversity of LGBT Elder Experience ................................................................................. 28

Living Arrangements: Alone but not Lonely?........................................................................ 30

LGBT Singlehood, Partnership and Kinship.......................................................................... 31

Geography ................................................................................................................................................. 33

Sexuality Over the Lifespan ............................................................................................................. 35

Ageism in LGBT Communities ....................................................................................................... 37

LGBT Elders in Prison ......................................................................................................................... 39

The Way Forward........................................................................................................................................... 42

Discrimination and Access to Services .................................................................................... 43

Cultural Competency..................................................................................................................... 44

Violence................................................................................................................................................. 48

Hate Violence............................................................................................................................. 48

Domestic Violence .................................................................................................................. 50

Elder Abuse................................................................................................................................. 51

Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 53

Financial and Family Security......................................................................................................... 54

Social Security Spousal Benefits............................................................................................ 57

Social Security Survivor Benefits ........................................................................................... 58

Military and Veterans Benefits .................................................................................................. 59

Medicaid Long-Term Care Benefits ...................................................................................... 59

Pensions ............................................................................................................................................... 60

Hospital Visitation and End-of-Life Decision Making.................................................. 61

Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 62

Health ............................................................................................................................................................. 63

Access to Health Care .................................................................................................................. 64

Lack of Insurance .................................................................................................................... 64

Experiences of Fear and Stigma..................................................................................... 69

HIV/AIDS............................................................................................................................................... 73

OUTING AGE 2010

Cancer ................................................................................................................................................. 75

Chronic Disease ............................................................................................................................... 77

Mental Health..................................................................................................................................... 80

Public Health Programs and Outreach ................................................................................ 84

Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................... 85

Caregiving, Social Isolation, and Housing .............................................................................. 86

Caregiving ........................................................................................................................................... 86

Social Isolation .................................................................................................................................. 89

Housing ................................................................................................................................................. 94

Housing Options for LGBT Older Adults .................................................................... 95

Homecare .................................................................................................................................... 97

Assisted Living .......................................................................................................................... 97

Naturally Occurring Retirement Communities...................................................... 100

LGBT-Targeted Elder Housing ....................................................................................... 101

Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 103

Civic Engagement, Lifelong Learning

and Elders in the Workplace ........................................................................................................ 104

Civic Engagement ........................................................................................................................ 104

Lifelong Learning .......................................................................................................................... 107

Workforce Issues .......................................................................................................................... 108

Policy Recommendations ................................................................................................................ 110

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................... 111

Key Recommendations ............................................................................................................. 112

Frameworks and Approaches for LGBT Aging Advocates ................................... 114

Key Organizing Opportunities on the Horizon.............................................................. 115

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................... 117

Appendix A:

How Big Is the LGBT Community? .................................................................. 132

Appendix B:

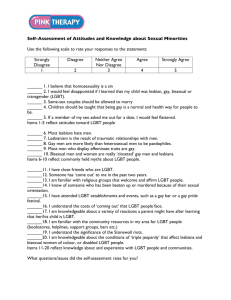

LGBT Cultural Competency Curricula ............................................................ 139

Appendix C:

A Roadmap to Federal Funding Opportunities .......................................... 141

Appendix D:

LGBT Aging Resources by Region ................................................................... 153

Appendix E:

LGBT and Aging State Non-Discrimination ................................................ 156

Laws and Policies

Task Force Policy Institute Bestsellers ...................................................................................... 158

National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Board .......................................................................... 159

National Gay and Lesbian Task Force Staff ............................................................................. 160

3

4

FOREWORD

Foreword

A

s a 42-year-old who has the great honor of doing this work, I owe a huge

debt to the pre-Stonewall and Baby Boomer generations of lesbian, gay,

bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people who literally put their lives and

livelihoods on the line to ensure that our movement for equality and justice

prevails. Our forbearers created the literature, community centers, newspapers,

grassroots and national organizations, legal protections and sense of possibility

that have formed the backbone of our communities. As these pioneering

generations of LGBT people move into their 70s, 80s, and 90s, I am struck by

the fact that many of them are compelled by circumstance to do what they have

always done in the face of anti-LGBT prejudice and inequality: create change.

I wish it were not so. I wish it was time to relax and say: job well done. But the

hard reality is, many LGBT elders are living in isolation and fear over how they

will sustain themselves as they age, and how they will be treated by providers

of aging services. While much has been accomplished through the passion,

persistence and indomitable energy of LGBT activists on aging over many years,

the aging boom is upon us, and the policies and practices essential to meeting

the needs of LGBT elders are simply not in place.

To address these challenges, the Task Force is proud to re-issue its landmark

book, Outing Age, ten years after its initial publication. What is the state of

aging for LGBT elders? What are our particular strengths and vulnerabilities?

What is the state of progress in federal, state and institutional policies that best

serve LGBT older adults? What can we point to in our organizing, advocacy and

creative adaptations over the past ten years as guideposts to future progress?

Outing Age 2010 charts this important territory.

Black lesbian feminist activist Audre Lorde has said that: “the learning process

is something you can incite, literally incite, like a riot.” If so, we offer this book

to incite the educational “riot” essential to revolutionary thinking and change

regarding the care and treatment of LGBT elders. It is clear that the task before

us requires strategic advocacy and tremendous determination. The Task Force

— along with Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE), statewide LGBT

organizations, local LGBT elder-serving groups and key allies like AARP — is

committed to shining a spotlight on the injustices that continue to create barriers

to aging with autonomy, dignity and affirming community.

OUTING AGE 2010

The scenario of LGBT adults being forced back into the closet for safety

in hostile elder environments is alarming and disgraceful. The Task Force

will ensure that Outing Age 2010 doesn’t sit on a shelf, but informs key

breakthroughs and advancements in advocacy. All of us must work together

to compel the federal government, the states, aging agencies and service

providers, local communities, and public health and housing programs to step

up to the challenge of meeting the vast, unmet needs of LGBT elders.

We must accept nothing less.

Rea Carey

Executive Director

5

6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

W

hen the Task Force published Outing Age in 2000, we brought

attention to the reality that LGBT-affirming and LGBT-specific elder

programs were all but non-existent. A decade later, most of the

principal barriers to healthy, empowered aging detailed in the first edition of

Outing Age persist:1

•

Research on LGBT people at the federal and state levels is almost nonexistent, and so the specific needs of LGBT elders remain largely invisible

and unaddressed.

•

Federal, state and local elder housing and care programs, Area Agencies on

Aging, and other providers have no mandate to provide culturally competent

services to LGBT people, while elders report widespread fear, discrimination

and barriers to care.

•

Federal “safety net” programs like Social Security and Medicaid define

family and partnership in ways that disempower and exclude LGBT families,

partners and spouses, creating economic and familial hardships for LGBT

elders.

•

Significant health disparities persist, with no federal commitment to

identifying or addressing them.

•

With no federal prohibition against anti-LGBT workplace discrimination in

place, income inequities across the lifespan persist for LGBT wage-earners.

•

LGBT people who spend their lives working and making productive

contributions to their families and communities remain at high risk in their

elder years for impoverishment, neglect and abuse at the hands of indifferent

aging systems and bigoted individual providers.

There is no doubt that 2009 was a harbinger of change for LGBT elder

advocates, after years of toiling against a tide of indifference, especially at the

federal level. In just one week in October, the Department of Housing and Urban

Development (HUD) issued new regulations prohibiting anti-LGBT discrimination

1

LGBT-Affirming refers to beliefs and actions that validate an individual’s right to identify and live

openly as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender.

OUTING AGE 2010

in HUD rental properties and public housing while the federal Administration

on Aging (AOA) announced funding for a national LGBT elder resource center.

HUD also committed to the first federal study on housing discrimination against

LGBT people in U.S. history.2 All of these reforms signal progress in the federal

government’s relationship to LGBT people as a whole, with positive implications

for elders seeking LGBT-affirming housing and care.

Federal and state legal landscapes over the next few years will shift considerably

for LGBT people. As this book goes to print, President Obama has signed the

Matthew Shepard/James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, providing landmark

federal protections to LGBT people against hate-motivated violence. Passage

of the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), stonewalled for over two

decades in Congress, appears imminent. The Department of Health and Human

Services has confirmed that it will commission a first-of-its-kind Institute Of

Medicine Report on LGBT Health, and is considering the creation of an Office of

LGBT Health. The Census Bureau is piloting research to improve data collection

on same-sex couples. Across the federal government, the question of how best to

pose LGBT questions in federal surveys is an active discussion.

These changes are a result of forty years of unwavering advocacy within the

LGBT movement. And while we must certainly pause for celebration, the

significant work of implementing these and the great many changes to come —

of pressing for accountability — is upon us. While we have spent the past four

decades raising the LGBT question, and arguing for our basic humanity, the next

four will entail shaping and enforcing policies that best serve the great breadth

of needs in our community. Within this transformative context, identifying and

addressing the needs of LGBT elders is paramount.

Accordingly, the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force urgently proposes this set

of comprehensive recommendations to appropriately address the LGBT aging

boom.

2

Also in October 2009: The LA Gay and Lesbian Center, one of the oldest and largest LGBT

organizations in the world, was awarded a grant from the federal government’s Administration

on Aging for its Aging-in-Place initiative; this is the first direct grant by the federal government

to an LGBT organization for aging services. Just two weeks later, Equality California announced

significant state funding for a youth and elder mental health research project, another historic

first.

7

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

KEY POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

•

The federal government and the states must fund and include questions

on sexual orientation and gender identity in all research surveys so that the

specific strengths and vulnerabilities of LGBT elders can be identified and

addressed.3

•

The federal Administration on Aging should issue guidelines to the states to

include LGBT elders as a “vulnerable senior constituency and identity” and

those with the “greatest social need.”

•

Pass the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA) to minimize workplace

discrimination over the lifespan so that LGBT people do not face their elder

years at an economic disadvantage. Enforce state and local employment

non-discrimination laws.

•

Enforce existing — and pass additional — state and local laws banning

discrimination on the basis of age, sexual orientation and gender identity and

expression in public accommodations such as senior centers, public housing

and nursing facilities.4

•

Reframe and expand the definition of family to recognize same sex

relationships and LGBT family kinship structures in the designation of federal

benefits such as Social Security, Medicaid and Veterans Benefits.

•

Pass federal and state legislation that ensures access to LGBT-affirming

health care for people of all ages and provides appropriate care for

transgender people.

•

Amend the federal Family and Medical Leave Act to cover LGBT caregivers

and their family and friends, regardless of whether they are related by blood

or marriage.

3

Key federal surveys include the Elder Abuse and Neglect Survey, the National Survey of Family

Growth, the National Health Interview Survey, the National Health and Nutrition Examination

Survey, the American Community Survey, and the decennial Census.

4

HUD’s recent announcement that it will explicitly ban discrimination against LGBT people in

subsidized rentals and public housing provides a key avenue for LGBT advocates to press

publicly funded elder housing programs to address anti-LGBT bias. To access the official press

release announcing the change: www.portal.hud.gov/portal/page/portal/HUD/press/press_

releases_media_advisories/2009/HUDNo.09-206

OUTING AGE 2010

5

•

Amend the Fair Housing Act and other housing laws to include specific

non-discrimination policies that protect LGBT people, and tie the receipt of

federal and state funding to compliance.

•

Call upon the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

to enforce its LGBT anti-discrimination regulations and to require grantees in

elder housing to obtain certification as culturally competent to serve LGBT

elders.

•

Press governmental agencies at the federal, state and local levels to

facilitate innovative funding programs for LGBT-targeted and LGBT-affirming

affordable and low-income housing.

•

Vigorously call upon and enforce the Joint Commission’s anti-LGBT

discrimination accreditation rules in assisted living facilities and nursing

homes to catalyze wholesale change in assisted living and nursing care for

LGBT people.

•

Train public and private healthcare providers in cultural competence for

working with LGBT older adults. Tie funding, accreditation and degree

requirements in medical, nursing and social work schools to LGBT cultural

competency certification.5

•

Develop and institute health promotion and healthcare-access policies and

programs specifically designed to bring needed care to older LGBT people

including, but not limited to, those living with HIV/AIDS.

•

Support a National AIDS Strategy that would include the establishment of

prevention, testing and treatment guidelines and programs designed to

specifically address the issue of HIV/AIDS among LGBT people ages 50plus.

•

Reach out to LGBT caregivers to inform them about services they can

receive from the National Family Caregiver Support Program.

•

Fund and develop programs that are specifically designed to address social

isolation among LGBT elders, such as LGBT-specific and LGBT-affirming

friendly visitor programs.

Cultural Competency refers to the ability of care providers to interact sensitively with members

of different cultural groups. Such care generally involves not only an acceptance of and respect

for difference, but also a degree of understanding of community norms, vulnerabilities and

practices.

9

10

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

FOR LGBT ORGANIZERS AND ADVOCATES,

WE OFFER THESE FRAMEWORKS AND APPROACHES:

Build Holistic, Strategic Approaches to Advocacy: What approaches promise

to address the needs of the broadest population of LGBT elders?

•

Securing universal health care access and culturally competent care would

meet the needs of elders across all income categories and family structures.

•

Developing LGBT-friendly public and affordable housing will meet the needs

of greater numbers of LGBT elders.

•

Prioritizing advocacy for a broader definition of family in federal programs

would address the needs of LGBT elders living in any/many different kinds of

family configurations, including single elders.

•

LGBT advocates would do well to think about peer movement coalitions that

are natural allies in the struggle for LGBT elder care, such as the disability

rights movement, racial and economic justice organizations, and HIV

advocates.

•

Given the limited capacity of the LGBT movement, what are the best

strategies for leveraging our passion and our strengths toward the greatest

good?

Finally, two critical opportunities for organizing and change lie on the horizon for

advocates in LGBT aging:

THE 2011 REAUTHORIZATION OF THE OLDER AMERICANS ACT (OAA)

In its current form, the Older Americans Act remains massively under

funded to meet the needs of all older Americans. Organizing for the 2011

reauthorization should focus intently on the importance of resource allocation

to meet the needs of the nation’s burgeoning aging population.

LGBT elders are also virtually invisible in the Act, which discusses the

importance of addressing the needs of “vulnerable senior constituencies”

but fails to name them. This has left LGBT advocates with an opening to

advocate for explicit language on LGBT people in the regulations for the

current Older Americans Act, something that is just underway as we go

to print with this book, and the Administration on Aging has committed

to funding a National LGBT resource center. Accordingly, a key point of

organizing for the 2011 reauthorization is explicit language that identifies and

defines “vulnerable senior constituencies.” Finally, defining and mandating

OUTING AGE 2010

culturally competent care for LGBT elders (and other vulnerable populations)

could be addressed in this bill, with LGBT advocates forming strategic

coalitions with other underserved communities.

THE 2015 WHITE HOUSE CONFERENCE ON AGING (WHCOA)

Every ten years, aging policy gets a major examination and revision through

the White House Conference on Aging. In 1995 and 2005, LGBT activists

pushed for inclusion in the aging agenda from a marginalized, outsider’s

position — movement pioneers Del Martin, Phyllis Lyon and Amber

Hollibaugh were among the advocates pivotal to these efforts. In 2015, the

LGBT communities, including experts in LGBT aging, must be on the inside

of the planning process for the WHCOA, and in the leadership that drives

the conversation and policy recommendations that flow from the gathering.

“Inclusion” of LGBT issues on a laundry list of concerns will not be enough.

Leadership by recognizable, accountable LGBT elder advocates and

researchers is essential.

The Task Force urges federal, state and local officials charged with the

care of LGBT elders, as well as advocates in LGBT aging, to take up these

recommendations with vigor and without delay.

11

Amirah Watkins-Brown Chicago, Illinois, 61

lesbians, seen as spinsters who

simply had not found the ‘right

man’ yet. And so when I did come

out to my mother, she expressed

fear for my safety and said, ‘I

just don’t want you to get hurt.’”

Amirah recalls that little changed

in Chicago in the wake of the

1969 Stonewall Riots in New York

City. “We still had the same police

harassment, from haters to the

police, and the police were usually

the more aggressive ones.”

A

mirah Watkins-Brown was

born in Jackson, Mississippi

in 1948. Her mother, who was of

German, Indian, and Irish descent,

experienced aggressive racism

for her relationship with Amirah’s

father, an African-American

man. The family soon moved

to Chicago in hopes of raising

Amirah in a more hospitable

environment.

At the age of 4, Amirah recalls

discovering her attraction to other

girls. “I had a little friend who lived

down the street and she would

come over to play and we became

fast friends. One day she declared

that we would play ‘house’ just

like her ‘Mommy and Daddy’ did.

And then she kissed me, and it

was absolutely the most glorious

feeling, and I thought to myself,

Wow, I want to do that again! And

I have been playing house with

women ever since!”

It was far from easy being

LGBT during the 60s and 70s

in Chicago. “It was crazy here.

Women were raped for being

In the 1990s, Amirah began

volunteering at the Howard

Brown Health Clinic in Chicago,

a hospital specializing in LGBT

health care. She became an

advocate for safer-sex practices,

speaking at health fairs in malls,

schools, college campuses, and

diversity expos.

Amirah began to identify a need

for culturally sensitive doctors

and medical services. She notes

that although LGBT people have

a far easier time now than they

did when she was younger, “we

have all of these ‘out’ people

running around, but what’s going

to happen to these people when

they need someone to take care

of them?” Amirah recalls the first

time that she felt homophobic

discrimination by her then-doctor.

“We were talking, very cordially

and friendly, and he started his

exam, checking my neck and

lymph nodes without any gloves

on. And we were chatting really

casually, and he asked me if I was

sexually active, and I said yes,

and then he asked me if there was

any chance I might be pregnant,

and I of course said no, and

then, he asked me if I was using

any protection, and I said, ‘No, I

sleep with women and that’s all

the protection I need.’ And I tell

you, once he found out I was in

a relationship with a woman, he

immediately put on gloves and his

demeanor totally changed after

that.”

Amirah began hearing similar

stories from LGBT friends and

realized the pervasiveness of

discrimination against LGBT

people in the medical field. “These

doctors and nurses and aides

seriously need sensitivity training.

I’ve heard it all: ‘The reason you

have a yeast infection is because

you’re a lesbian;’ or, ‘The reason

you have eczema or acne is

because you’re gay.’ It’s just the

typical bull you hear from nonculturally competent doctors.”

“I believe all of us are created

equally—and I say that whether

you’re polka-dotted, straight,

green, whatever. Who you are,

or whoever you love or whatever

you do, doesn’t need to be

understood by everybody, but it

does need to be respected.”

OUTING AGE 2010

Why This Book?

Mr. Jordan stated that he is a 59-year-old female-to-male transsexual

of mixed race. Being a poor, minimum wage worker, he is dependent on

the public healthcare system. He has been in nursing care facilities and

sees horrible treatment of queers there. He stated that should his life

deteriorate to [that] point, he would rather kill himself than live in such

circumstances.

—Report of the San Francisco Human Rights Commission

(October 2002)

I

n 2000, the Task Force released a groundbreaking report, Outing Age,

which exposed the collision of ageism, sexphobia, and homophobia that

makes dignified, secure aging as a lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender

person a process fraught with obstacles.6 American society commonly views

older adults as asexual while perceiving LGBT people as universally young

and sexually rebellious. The simultaneous impact of these prejudices renders

6

Ageism refers to prejudicial feelings or actions based on beliefs about the limitations of abilities

due to age, most often directed against elders or youth. Institutional ageism manifests in

poor policies that belittle or demean people based on age, such as elder care policies that

infantilize, desexualize or disempower elders.

Sexphobia means fear of sex; while our culture is rife with images of commercial sexuality,

sexphobia refers to the fear of authentic, empowered expressions of sexuality across the wide

spectrum of possibilities. Institutional sexphobia may be expressed in abstinence-only sex

education programs, or a failure to address sexuality in health care or elder care.

Homophobia refers to feeling or actions based on hatred, aversion or fear of same-sex

attraction and sexual behavior among lesbian, gay or bisexual people. Non-conforming gender

expressions often incite homophobic responses. Institutional homophobia is expressed in

systemic discrimination such as workplace or public policy inequities based on perceived or

actual sexual orientation.

Lesbian and Gay refers to individual people who are romantically and/or sexually attracted to,

and/or partner with people of the same gender; lesbians partner with women and gay men

partner with men.

Bisexual people are romantically and/or sexually attracted to, and/or partner with people of

more than one gender.

Transgender describes people who identify with or express a gender different from the sex

assigned to them at birth.

13

14

WHY THIS BOOK?

LGBT elders at best invisible and at worst expendable.7 The original edition of

Outing Age explored this quandary in detail, revealing a dearth of resources to

support LGBT older adults and making policy recommendations to address the

inequities these elders face.

In the 10 years since its publication, Outing Age has had a tremendous impact

on both the field of aging and the LGBT community. While only a handful of

local and national LGBT groups in the United States addressed aging in 2000,

the ensuing decade saw the building of numerous LGBT elder-specific projects

and organizations. Concurrently, the nation’s vast aging apparatus increasingly

awoke to the reality of LGBT aging and began to respond:

•

The American Society on Aging’s LGBT Aging Issues Network, formally

recognized in 1994, has become a major resource in LGBT aging over the

past 15 years.

•

The 2005 White House Conference on Aging was pushed to address LGBT

issues, as a result of significant preconference organizing by the Task Force

and its allies.

•

AARP created an Office of Diversity and Inclusion that addresses sexual

orientation as one of its concerns. The organization’s “Divided We Fail”

campaign recruited the Task Force and other major LGBT advocacy

organizations as endorsing partners.

While major policy gains for LGBT elders have been limited, a few significant

advances have created new protections and possibilities at the national level

and in two leading states:

•

The Department of Housing and Urban Development has issued LGBT antidiscrimination regulations in publicly funded housing, with explicit language

re-defining “family” so that LGBT families do not face impediments to

qualifying for HUD programs.8

7

The terms elders and older adults refer to people 65 years and older, the current standard age

of retirement in the U.S.

8

HUD has announced its intention to: “clarify that the term ‘family’ as used to describe eligible

beneficiaries of our public housing and Housing Choice Voucher programs include otherwise

eligible lesbian, gay, bi-sexual or transgender (LGBT) individuals and couples. HUD’s public

housing and voucher programs help more than three million families to rent an affordable

home. The Department’s intent to propose new regulations will clarify family status to ensure its

subsidized housing programs are available to all families, regardless of their sexual orientation

or gender identity.” To see the press release, go to: www.portal.hud.gov/portal/page/portal/

HUD/press/press_releases_media_advisories/2009/HUDNo.09-206

OUTING AGE 2010

•

The Administration on Aging has announced funding for the creation of a

national LGBT resource center.

•

Massachusetts and Vermont provide state-based safety nets for LGBT

same-sex couples that cover the costs of the community spouse retaining a

jointly owned home in the event of one partner needing long-term, Medicaidfinanced care.9

•

In 2007, California passed the Older Californians Equality and Protection Act,

which requires Area Agencies on Aging throughout the state to include LGBT

people in their data gathering and planning and in regional and local services

development.10

•

Updated language in the 2006 reauthorization of the federal Older Americans

Act extended the definition of caregiver beyond legally married spouses and

blood relatives, enabling members of LGBT chosen families to qualify for

benefits under the Family Caregivers Support Program for the first time.11

•

The federal Pension Protection Act of 2006 provides a direct rollover option

to nonspousal beneficiaries of pension plans, enabling them to avoid tax

penalties. Any person in an LGBT elder’s chosen family—spouse, unmarried

partner, or other chosen family member may be designated a beneficiary and

receive these benefits.12

•

In 2002—2003, the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations (now the Joint Commission), the key body that accredits

healthcare facilities nationwide, added respect for sexual orientation to its

patient rights’ requirements for assisted living and skilled nursing facilities.

This provision gives LGBT advocates a formal policy to press when

confronting discrimination in service delivery.13

9

“Community spouse” is a term used to refer to an individual living in the community who has a

partner living in long-term care.

10

Older Californians Equality and Protection Act, (2007). A.B. 2920

11

See The Older Americans Act of 1965. (1965). P.L. 89-73: Title III(A), Sec. 302(3) as amended by

P.L. 109-365, enacted October 17, 2006

12

The Pension Protection Act of 2006. (2006). P.L. 109-280: Sec. 829(a)(II)

13

American Society on Aging. (2003, March). Assisted Living Standards to Recognize Sexual

Orientation. ASA Connection. Retrieved from www.asaging.org/asaconnection/03mar/pplink.

cfm

15

16

WHY THIS BOOK?

These gains are laudable, but in the bigger picture of LGBT aging, they are

limited. The very recent changes at the federal level herald a brighter day for

LGBT elders, yet to be realized. At the state level, the California legislation

provides an outstanding example of appropriate state intervention on behalf of

LGBT elders, but it is an unfunded mandate, with no money included to ensure

cultural competency training. Nor has the law been replicated in other states.

Similarly, the Joint Commission’s policy on nondiscrimination in long-term care

currently exists largely on paper; standard-setting, monitoring, enforcement

and requirements for cultural competence training remain to be put in place.

In general, LGBT elders continue to face tremendous barriers to aging in safe,

affirming environments:

•

Workplace discrimination over the life course leaves LGBT people

economically vulnerable as they approach their later years.

•

The legal disenfranchisement of LGBT chosen families—whether spouses

and partners or extended networks of intimate friends—renders LGBT

support systems fragile and economically disadvantaged.14

•

The presumption that all elders are heterosexual creates unwelcoming

conditions for LGBT people in aging services, healthcare and other

institutional settings.15

•

LGBT-affirming elder housing and culturally competent care is nearly

nonexistent.

•

The assets of LGBT older adults continue to be drained and compromised

by discriminatory policies in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid.

•

LGBT older adults who came of age before the gay liberation movement

of the 1970s have lived largely in the context of extremely hostile social,

medical and mental health systems, making self-advocacy within aging

services agencies or institutional settings overwhelmingly difficult for many of

these elders.

14

Legal disenfranchisement refers to the deprivation of legal rights, in this case pertaining to the

LGBT community.

15

Heterosexism, heterocentrism and heteronormative are all words used to signify the

presumption, active in almost all social contexts, that everyone is heterosexual until proven

otherwise. Institutional heterosexism is expressed by policies and practices that reflect that

presumption, often rendering LGBT people and their families invisible.

OUTING AGE 2010

•

Older adults who came of age after the Stonewall Rebellion have had to

blaze a path toward LGBT equality their entire lives, yet face their elder

years with the same daunting task ahead of them—needing to advocate for

respect and equal treatment from the institutions and services essential to

their well-being.16

•

Ageism in LGBT communities adds to the burdens faced by LGBT older

adults, leaving many of our elders isolated or alienated from the larger LGBT

community.

Nearly a decade after the original publication of Outing Age, the Task Force

offers Outing Age 2010 as an update on both the barriers faced by our elders

and the progress made toward creating a safe and dignified old age for all LGBT

people. This new edition was sparked by such questions as the following:

•

What do we know now that we didn’t know in 2000 about the vulnerabilities

and strengths of LGBT elders?

•

How do homophobia and transphobia in the workplace affect our economic

security as we age?

•

What is the impact of the HIV epidemic on LGBT older adults?

•

What is the continuing effect of racism on the ability of LGBT

elders of color to achieve economic security and appropriate housing and

health care?

•

What options exist for LGBT people wishing to remain in their homes and

communities?

•

What success are we having in obtaining funding LGBT-specific services for

older adults?

These are just a few of the critical concerns we address in this report. The

Task Force presents Outing Age 2010 as both a resource for—and a challenge

to—professionals and policymakers charged with meeting elders’ needs. All

LGBT people deserve to age in caring, LGBT-positive, sex-positive, culturally

competent environments that respect their decisions about how open they

wish to be regarding their sexual orientation and gender identity. The system of

services for older adults in the United States must adapt to the reality that this

16

The Stonewall Rebellion is widely regarded as the igniting event of the modern LGBT rights

movement. In June of 1969, gay and transgender patrons of the Greenwich Village Stonewall

Inn bar rioted for three days against police brutality and harassment.

17

18

WHO ARE ELDERS IN AMERICA IN GENERAL?

The courage and

tenacity of LGBT

older adults

have created

a new world of

possibility for

LGBT people of

every generation

to come.

generation of LGBT elders has created with such grace and

determination: the days of the enforced closet are long over.

LGBT elders who find themselves in the nation’s wideranging system of aging-related benefits, institutions and

services must not be shamed or marginalized. The courage

and tenacity of LGBT older adults have created a new

world of possibility for LGBT people of every generation to

come. At the Task Force, we are committed to working to

ensure that the sacrifice and determination of these elders is

rewarded by an increasingly safe, economically secure and

joy-filled old age.

Outing Age 2010 is a fresh demonstration of this

commitment.

OUTING AGE 2010

Who are Elders in America in General?

W

e know a good deal about older Americans, thanks to significant data

gathering by the government agencies like the United States Census

Bureau, the Administration on Aging in the Department of Health and

Human Services, as well as advocacy organizations such as AARP and the

Older Women’s League, and by academic gerontologists.

A RAPIDLY GROWING POPULATION

The population of people ages 65-plus in the United States has grown

dramatically over the past century, largely due to increased life expectancy.

While the U.S. population overall has tripled in this period, the elder population

has increased twelvefold. Today nearly 37.9 million Americans are 65 or older,

representing 12.6% of the population, or one in eight Americans. Most older

Americans are women: more than 21.9 million, versus 16 million men. Fifty-one

percent of elders are 65—74 years of age, 34% are 75—84, and 15% are 85 or

older. A substantial increase will occur between 2010 and 2030, after the first

of the baby boomers turn 65 in 2011. In that period, the number of elders in the

U.S. will nearly double, from 37.9 million to 72.1 million, at which point, one in

five Americans will be 65 or older.17

AN INCREASINGLY DIVERSE POPULATION

Today, people of color make up roughly 20% of the population of elders in the

United States.18 Eight percent are African American, 6.6% Hispanic, 3.2% Asian/

Pacific Islander, and less than 1% Native American.19 Projections indicate that

by 2030, the composition of the older population will be more diverse: 72% will

be non-Hispanic white, 11% Hispanic, 10% Black, and 5% Asian. The older

Hispanic population is projected to grow rapidly, from just over 2 million in 2003

to nearly 8 million in 2030, at which point it will surpass the size of the older

Black population. The older Asian population is projected to grow from nearly 1

million in 2003 to 4 million by 2030.

17

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008). A Profile

of Older Americans: 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2009, from www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_

Statistics/Profile/index.aspx

18

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

19

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

19

Shaba Barnes Albuquerque, New Mexico, 73

graduate degrees and stay in their

chosen career most of their life.

They earned good wages and

were thus able to save more for

the future.”

A

lthough she counts

Copenhagen, Casablanca,

London, Paris, Spain, and the

Island of Menorca among her

all-time favorite places in the

world, Shaba Barnes says she will

always be an “East-Coaster” at

heart. Born in 1935 in New York

City, she grew up in an Orthodox

Jewish family of African American

descent, and remembers

searching passionately for her

own sense of spirituality and

purpose while growing up. She

met her partner of 40 years while

living in New York, and together

raised their four children, who

then provided them with 16

grandchildren and 10 greatgrandchildren.

As a young lesbian, Shaba

remembers that while she and

her partner both worked multiple

jobs, they were always struggling.

“I noticed that many of my white

peers often had families with

money. They entered the higher

income bracket because they

were able to complete college

at an earlier age, receive their

At 33, Shaba moved to Los

Angeles and found her calling as

a New Thought Minister in 1980.

She became a regular minister at

a church in L.A., landed a weekly

radio show, and became involved

in Women Prison Ministries. It

was around this time that Shaba

helped lay the groundwork

for what would become one

of the premier lesbian aging

organizations in the country,

OLOC (Old Lesbians Organizing

for Change).

“There’s a lot to be said about

being in the right place at the right

time. It was early 1986 when I

received a phone call from a friend

whom I had met years earlier at

a feminist bookstore, asking me

to help plan a West Coast ‘get

together’ for older lesbians, 60+

over.” The conference became

the focal point for OLOC—to

empower and celebrate older

lesbians, and to fight ageism

within the LGBT community as

well as at large. Ageism has been

a difficult challenge to eliminate.

Even many of the Old Lesbians

enact internalized ageism. They

do not want to be called ‘old.’

They prefer to be called elders,

seniors, older, but never old.

The term that sets us apart, the

very word that empowers us, is

whispered behind our backs by

others, effectively dismissing us

as out-of-touch, irrelevant, or

discounted.”

Nevertheless, Shaba notes

progress in confronting ageism

within the LGBT community in

the last few years. “I particularly

want to point out the changes

that I have witnessed at NGLTF’s

Creating Change conference.

For many years OLOC members

facilitated workshops caucuses,

speaking mostly to ourselves and

our own generation about ageism.

Today, I see day-long institutes

with speakers drawing all cultures

and ages of LGBT participants

who are all working, sharing, and

getting together to discuss issues

surrounding ageism. This year

(2009) was the first time we were

invited to participate in the all-day

intensive institute around aging.”

Shaba notes, however, that there

is still much work to be done.

Eventually, Shaba hopes that the

community will come to recognize

that aging is an issue germane to

people in all stages of their lives,

that aging is something that we

should all hope to experience.

“We need to have dialogue

about how ageism works. Our

community and our society

function like a domino effect:

when OLOC gains a victory, we all

gain that victory. After all, aren’t

we all swimming in this same river

called Life?”

OUTING AGE 2010

PEOPLE ON LIMITED INCOMES

Federal data demonstrates that poverty is a stark reality for millions of older

Americans—and the income thresholds set in federal definitions of poverty are

so low that they clearly underestimate the problem.20 In 2007 the median annual

income of Americans 65-plus was $24,323 for males and $14,021 for females.

About 3.6 million elders (or 9.7%) lived below the poverty level, defined as

$9,944 for an individual age 65 or older. Another 2.4 million (6.4%) are classified

as near-poor, with their income falling between the poverty level and 125% of

that level. Without support from Social Security, the official poverty rate among

elders would rise from 9.7% to nearly 47%.21

A number of interrelated factors increase the likelihood of poverty among elders

in the United States, as the following data from the federal Administration on

Aging indicates.22

•

Older women experience a higher poverty rate (12%) than older men (6.6%).

•

Elders living alone or with nonrelatives are more likely to be poor (17.8%)

than are those living with their families (5.6%).

•

One of every 14 whites ages 65-plus are poor (7.4%), compared to nearly

one in four Black elders (23.2%); about one in six Hispanic elders (17.1%);

and more than one in 10 Asian elders (11.3%).

•

The highest rates of poverty among elders were experienced by Hispanic

women who live alone (39.5%) and African American women who live alone

(39%).

•

Older people living in rural and urban areas, as well as in the South and

Southwest, are more likely to live in poverty than are those in other parts of

the country.

20

In 2008, with the exception of Alaska and Hawaii, the federal poverty level for a household of

one was $10,830 and for a household of two was $14,570. See US Department of Health and

Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2009). HHS Poverty Guidelines. Retrieved August

29, 2009, from www.aspe.hhs.gov/poverty/09poverty.shtml

21

The statistics on income and poverty levels for elders are drawn from US Department of Health

and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

22

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

21

22

WHO ARE ELDERS IN AMERICA IN GENERAL?

•

The District of Columbia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico and

North Dakota have the highest rates of elder poverty (ranging from 13% to

14.6%).

Disproportionate poverty among Black and Latino elders is partly an outcome of

their lower levels of educational attainment compared to non-Hispanic whites.

This disparity is a result of institutionalized racism as reflected in segregated and

lower-quality schools and in the disproportionate impact of poverty on Black

and Latino elders’ families of origin, which forced many to leave school early to

join the workforce. While 81% of older whites graduated from high school, only

57% of Black and 42% of Hispanic elders did. And while 20% of elders overall

graduated from college, only 11% of Black elders and 9% of Hispanic elders

did. Lower levels of educational attainment, lower lifetime earnings, and fewer

years in the workforce—also due in large part to sex and race discrimination—

mean that women and people of color have lower incomes in retirement, as

pensions and Social Security pay more to those with a history of higher earnings

and more years of paid work.23

LIVING ARRANGEMENTS

About 30% of elders in the United States lived alone in 2007. Only 19% of older

men lived alone, versus 38% of older women; this is in large part due to the

longer life expectancy of women.24 About 5% of women and 4% of men ages

65-plus have never married.25 A relatively small percentage of the population

ages 65-plus—4.4% (or 1.57 million)—lived in nursing homes in 2007.26 The

percentage increases dramatically with age, ranging from 1.1% for those

65—74 years old to 4.7% for those 75—84 and 18.2% for those ages 85-plus.27

Additionally, approximately 5% of older adults live in self-described senior

housing of various types, many of which have supportive services available to

their residents.28

23

See sections, “Geographical Distribution” and “Poverty,” in US Department of Health and

Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

24

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

25

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

26

See section, “Living Arrangements,” in US Department of Health and Human Services,

Administration on Aging. (2008).

27

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

28

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

OUTING AGE 2010

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION

The population of older adults in the United States is concentrated in a number

of states, with some clear clustering around race and culture. In 2000, almost

three-quarters of all older Hispanics lived in four states: California, Florida,

Texas, and New York. Nearly two-thirds of older Asians lived in the West.29

Florida—traditionally a popular retirement destination—has the highest

percentage of elders, with 18.5% of its population ages 65 or older. Other states

with significant elder populations are Pennsylvania and Rhode Island at 15.8%

each, and Iowa at 15%.30

29

He, W., Sengupta, M., Velkoff, V., & DeBarros, K. (2005). 65+ in the United States: 2005. US

Census Bureau. Retrieved August 29, 2009, from www.census.gov/prod/2006pubs/p23-209.pdf

30

US Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging. (2008).

23

24

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT LGBT ELDERS?

What Do We Know

About LGBT Elders?

Despite extensive general data on elders and decades of advocacy by LGBT

activists, only a handful of state and federal demographic and health surveys

collect data on LGBT elders.31 As a consequence, when seeking data on the

total number of LGBT older adults, their geographical distribution, their health

and economic status, their need for supportive services and other crucial

concerns, we often are forced to draw on qualitative rather than quantitative

data—or must extrapolate from limited samples or research on related groups.

These approaches help us identify many of the basic issues of LGBT aging—

and help us raise important questions which demonstrate that comprehensive,

fully funded research about LGBT elders is needed at the national and state

levels. One thing is abundantly clear from the limited data at hand: LGBT elders

remain an underserved and highly vulnerable population.

Much of what we currently know about LGBT elders in the United States comes

from the pioneering social science research conducted by a handful of scholars

since the mid-1970s. Most of these studies rely on cohorts of white gay men;

a smaller number focus on lesbians. Very few include transgender or bisexual

elders or examine the findings to discern issues of particular concern to these

elders.32 And most of the studies involve small sample sizes that do not reflect

the racial and economic diversity of the LGBT community.33

Gilbert Herdt and his colleagues reported in 1997 that, “in the case of older

bisexuals, lesbians and gays, the combination of poor research literature,

clinical samples, and dated historical narratives from prior generations has

had the effect of making this population appear more homogeneous than it is,

31

The National Survey of Family and Social Growth, statewide Youth Risk Behavior Surveys in

a handful of states including Massachusetts and New York, the California Health Interview

Survey, The Harvard Nurses survey and a few state tobacco surveys ask questions about

sexual orientation. This patchwork of largely health surveys gives us a fragmented view of the

health and social issues in LGBT people lives.

32

One study that has been published is Witten, T. M. (2002). “Geriatric Care and Management

Issues for the Transgender and Intersex Population”. Geriatric Care and Management Journal,

12(3)

OUTING AGE 2010

undercutting diversity in life-course experience.”34 In the more than a decade

that has passed since that assessment, the research literature on LGBT aging

has been grown in both depth and sophistication, but large-scale and long-term

quantitative research on LGBT aging largely remains to be done; in addition,

many crucial areas of concern have received little or no attention, even in

qualitative studies.

A groundbreaking 1999 report by the Committee on Lesbian Health Research

Priorities of the Institute of Medicine underscores the limited research on

lesbians in the United States, noting that “most existing studies portray crosssections of experience at one point in time and so cannot address compelling

questions of behavior, identity, or attraction across time. Prospective,

longitudinal studies are essential for understanding the vulnerability, resilience,

and well-being of lesbians across their life span.”35 Such studies would have

particular significance for illuminating the strengths and vulnerabilities of

lesbians in midlife and old age which reflect not only their current circumstances

but also the legacy of their earlier life experiences.

Future research must do better at gathering information on all LGBT elders,

including people-of-color, low-income, and immigrant populations. The following

sections synthesize what we know about LGBT older adults or can reasonably

argue regarding LGBT elders on the basis of research on LGBT people in

general.

33

“Almost without exception,” as one social science literature review notes, studies of older gay

men have disproportionately focused on “white, middle class, well-educated, urban-dwelling

men who participate in the gay community through friendship networks, gay bars, support

organizations, etc.” See Wahler, J., & Gabbay, S. G. (1997). “Gay Male Aging: A Review of

the Literature”. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 6(3), p.5. Another reviewer notes

the pressing need for research which examines “the significance of ethnicity, poverty, and

heterosexism among aging gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals.” See Boxer, A. (1997). “Gay,

Lesbian, and Bisexual Aging into the Twenty-First Century: An Overview and Introduction.”

Journal of Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Identity 2(3-4), p.191.

34

Herdt, G., Beeler, J., & Rawls, T. (1997). “Life-Course Diversity among Older Lesbians and Gay

Men: A Study in Chicago.” International Journal of Sexuality and Gender Studies 2(3-4).

35

Solarz, A. (ed.) (2008). “Lesbian Health: Current Assessments and Directions for the Future.”

Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from www.nap.edu/catalog/6109.html.

25

26

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT LGBT ELDERS?

HOW MANY LGBT ELDERS ARE THERE?

We are able to report at best a qualified estimate of the number or percentage of

lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender elders in the U.S. population for the same

reason we cannot give an exact number of the total LGBT population of all ages:

In addition to definitional challenges presented by the categories themselves,

few national surveys ask about sexual orientation and fewer still about gender

identity.

In this report, we draw on findings from a 2009 gathering of 34 leading LGBT

researchers who reviewed the limited existing data and literature to establish a

demographic estimate of the LGBT community in the United States as ranging

between 5% and 10% of the population at large. See appendix A for this

discussion, which points to the need for the U.S. Census Bureau and other

federal agencies to gather data on the LGBT population. Taking the statistic of

LGBT people as constituting 5% to 10% of the population and extrapolating

from federal statistics for the number of older adults in the general population,

we estimate that between now and the height of the aging boom, there will be

approximately nearly 2 million to as many as 7 million LGBT elders in the United

States.

CLASS, RACE AND GENDER IN AGING

The paucity of national data means that we know little about the racial and class

diversity in the LGBT community in general and among LGBT elders in specific.

Nonetheless, Lora Connolly, chief deputy director of the California Department

of Aging, has said that there is no reason to believe that the LGBT community is

any less racially diverse than the overall population in the United States.36

Recent studies show that lifelong experiences of social and economic

marginalization place lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender elders at higher risk

for isolation, poverty and homelessness than their heterosexual peers.37 Given

this fact, LGBT elders are undoubtedly among those with the greatest economic

and social need. Income data for LGBT older adults drawn from scattered local

surveys reinforces this observation:

36

California Department of Aging. (2009). California State Plan on Aging 2005-2009. Retrieved

August 29, 2009, from www.aging.ca.gov/whatsnew/california_state_plan_cda_2005-2009.pdf

37

See, for instance, Albelda, Randy, et al. (2009) Poverty in the Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual

Community. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute. Available at www.law.ucla.edu/

williamsinstitute/pdf/LGBPovertyReport.pdf.

OUTING AGE 2010

•

Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE), which serves New York

City, reports that approximately 35% of its clients are Medicaid eligible, with

annual pretax incomes below $10,000; an additional 35% subsist on annual

pretax incomes of $20,000 or less.38

•

The Chicago Task Force on LGBT Aging reports that 8.8% of LGBT older

adults in Chicago have an annual income under $10,000, which would put

them below or near the poverty line.39

•

The San Diego LGBT Needs Assessment identified 14% of LGBT people

over 65 reporting incomes of $10,000 or less and 10% reporting incomes

under $20,000. None of the respondents reported incomes over $100,000.40

A recent study from The Williams Institute drawing on census data on samesex couples and on figures from two other federal surveys that ask about LGBT

identity or sexual behavior similarly describes the economic challenges faced by

LGBT elders.41 Comparing couples which include members ages 65 and older,

the study found poverty rates of 4.6% for opposite-sex married couples, 4.9%

for male same-sex couples and 9.1% for female same-sex couples. The study

also found that the following factors are associated with higher rates of poverty:

being Black; living in nonurban areas; living in the East, West, or North Central

regions of the country; having only a high school diploma; being out of the labor

force; and having children. These intertwined factors reflect multiple economic

vulnerabilities for many LGBT elders, coupled or not.

The Transgender Law Center notes that transgender Californians are highly

educated yet twice as likely to live below the poverty line of $10,400 compared

to the general population.42 The Task Force’s forthcoming national study on

discrimination against transgender people found an unemployment rate double

38

Thurston, C. Services and Advocacy for GLBT Elders (SAGE). Journal of Long Term Home

Health Care (forthcoming Fall 2009).

39

Beauchamp, Dennis, Skinner, Jim, Wiggins, & Perry. (2003). LGBT Persons in Chicago: Growing

Older. A Survey of Needs and Perceptions. Chicago Task Force on LGBT Aging.

40

Cook-Daniels, L. (2004). LGBT Seniors-Proud Pioneers: The San Diego County LGBT Senior

Healthcare Needs Assessment. Retrieved September 21, 2009, from www.sage-sd.com/

SeniorNeedsAssessment.

41

Albelda, R., et al. (2009). Poverty in the Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Community. Los Angeles:

The Williams Institute. Retrieved August, 29, 2009, from www.law.ucla.edu/williamsinstitute/

pdf/LGBPovertyReport.pdf.

42

Transgender Law Center. (2009). The State of Transgender California Report. Retrieved October

14, 2009, from www.transgenderlawcenter.org/pdf/StateTransCA_report_2009Print.pdf.

27

28

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT LGBT ELDERS?

that of the national unemployment rate among its 6,500 respondents. Fourteen

percent of respondents 65 years and older reported incomes below $10,000 and

51% reported an adverse job action.43

Some studies suggest that gay men and lesbian women age differently. There

is some indication that gay men experience what is referred to as “accelerated

aging,” seeing themselves as old as early as their 30s due to the premium

ascribed to youth and beauty in gay male culture; first advanced in popular

literature in the 1960s, this analysis has remained a subject of debate among

researchers.44 Conversely, older lesbians, many of whom came of age during

a period of the women’s movement that rejected traditional notions of beauty

and ageism, report a sense of freedom in their elder years, despite generally

having more economic challenges than their male counterparts.45 Gender

nonconforming and transgender people, by contrast, reach old age in a social

context of rigid gender categories that have largely excluded and demeaned

them.46

THE DIVERSITY OF LGBT ELDER EXPERIENCE

A common mistake that well-intentioned providers make in serving LGBT

elders is to see the community as monolithic—and thus to assume that events

meaningful to relatively gender-conforming, white, middle-class members of this

population may apply to all LGBT older adults. In fact, LGBT communities are as

diverse as their heterosexual counterparts, and our elders’ strategies in surviving

the myriad challenges they have faced in the different contexts in which they

have lived are greatly varied. Anti-LGBT stigma and discrimination is a shared

43

Grant, J., et al. (Forthcoming). Report on National Transgender Discrimination Survey. National

Gay and Lesbian Task Force Policy Institute & National Center for Transgender Equality.

44

For an overview, see Bennett, K. C. & Thompson, N.L. (1991). “Accelerated Aging and Male

Homosexuality: Australian Evidence in a Continuing Debate.” Gay Midlife and Maturity. Lee, J.

A., ed. New York, NY: Haworth Press, pp.65—75.

45

Two classic texts that summarize feminist and lesbian critiques of ageism are the following.

Copper, B. (1987). Ageism in the Lesbian Community. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press;

Macdonald, B., & Rich, C. (1983). Look Me in the Eye: Old Women, Aging and Ageism. San

Francisco: Spinsters Ink.

46

Gender nonconforming people express their gender differently from dominant cultural norms.

Some gender nonconforming people reject the categories “male” and “female” entirely; others

consider themselves a blend of both genders. In lesbian and gay communities, butch lesbians

and feminine gay men have long been targets of abuse for their gender non-conformity. In

recent years, a number of new terms like “genderqueer,” “gender bending” and “gender

blending” emerged as a fluid range of gender identities and expressions have taken hold.

OUTING AGE 2010

challenge that may or may not connect LGBT elders across

the many different identities and communities in which they

are situated.

The current generation of LGBT elders of various genders,

races and economic strata ground their later years on

differing defining moments and sociopolitical contexts. For

many gay men, for example, the post-Stonewall era of gay

liberation is formative, whereas for many white lesbian and

bisexual women, feminism and the women’s movement loom

largest. For African American, Latino and Asian LGBT elders,

the civil rights and labor struggles of the 1960s, as well as

experiences in their church communities, may provide their

grounding for old age. For LGBT immigrants, the trauma

of having survived armed conflict, government repression

and flight from their homelands often is a defining factor in

how they experience their elder years. Among transpeople,

the Stonewall rebellion in 1969 in New York City and the

recently recovered history of the Compton’s Cafeteria riot

in 1966 in San Francisco have strong symbolic resonance

as sites of resistance; at the same time, the greatest growth

in transgender visibility and activism has occurred only

in the past 10 to 15 years, making it very likely that many

transgender elders have spent the bulk of their lives in

isolation, navigating extremely hostile social and workplace

environments.47

Anti-LGBT

stigma and

discrimination

is a shared

challenge that

may or may not

connect LGBT

elders across the

many different

identities and

communities in

which they are

situated.

Researchers in the field of aging often note that people age

as they have lived. LGBT elder resilience will vary greatly

relative to the challenges these older adults have faced

and depending on the resources to which they have had

access across the lifespan and across cultures. Black lesbian

feminist Pat Parker gave this legendary caveat to white allies

in the 1980s about addressing the totality of her experience:

“First thing you do, is to forget that i’m Black/ Second,

47

29

The first documented public protest by transgender people was a peaceful sit-in of Dewey’s

Lunch Counter in Philadelphia in 1965 to protest its refusal to serve transgender patrons;

LGBT people picketed the restaurant collectively. In San Francisco’s Tenderloin District in

1966, transgender patrons of Gene Compton’s Cafeteria spontaneously protested against

police harassment there, and were arrested. See the Movement Advancement Project. (2009).

Advancing Transgender Equality, p.8.

30

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT LGBT ELDERS?

you must never forget that i’m Black.”48 Professionals in aging would do well to

extrapolate from and apply Parker’s standard to their work with a diverse range

of LGBT clients.

LIVING ARRANGEMENTS: ALONE BUT NOT LONELY?

Limited existing research provides some evidence that lesbian and gay elders

are more likely to live alone than are heterosexual older adults. Populationbased data collected by the New York City Department of Health in 2005-2007

suggests that among adults over 50, gay and bisexual men are twice as likely to

live alone as are heterosexual men, while lesbian and bisexual women are about

one third more likely to live alone than are heterosexual women.49 Another study

found that 75% of gay and lesbian elders in Los Angeles lived alone.50 This high

percentage was confirmed in a 2006 study of LGBT older adults living with HIV/

AIDS — which reports that almost 70% of its participants live alone.51

Such statistics may suggest that LGBT older adults in general are vulnerable to

certain physical and mental health challenges for which elders who live alone

are at greater risk; these include falls, malnutrition, depression, and substance

abuse.52 At the same time, LGBT elders’ life experience may in some ways

provide them greater personal resources for coping with living alone. A 2006

study found, for instance, that almost 40% of LGBT baby boomers believe

that being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender has helped them prepare

for aging by endowing them with positive character traits, greater resilience,

48

Parker, P. (1999). Movement in Black. Ann Arbor, MI: Firebrand Books, p.68.

49

Prevalence of Living with No Other Adults/with Children among Adults age 50+ in New York

City by Sexual Identity. NYC Community Health Survey, 2005 through 2007. All estimates

are weighted to the NYC population, Census 2000 and age-adjusted to the US Standard