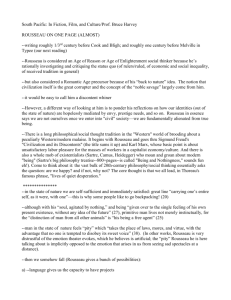

Jean-Jacques Rousseau and - Open Research Exeter (ORE)

advertisement