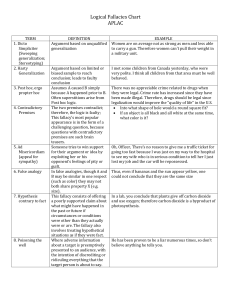

attacking faulty reasoning

advertisement