C.S. Lewis, author of The Four Loves, has claimed that lovers are

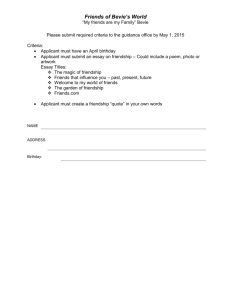

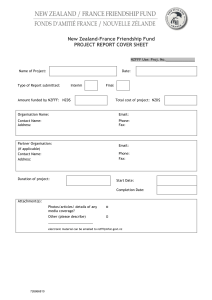

advertisement

C.S. Lewis, author of The Four Loves, has claimed that lovers are absorbed in each other while friends are absorbed in some common interest. Discuss and evaluate this claim about the distinction between love and friendship. Brad Knott The standard way of thinking about romantic love and companion friendship has it that romantic love falls into a distinct, separate category due to the element of sexual intimacy. Traditionally, it has been claimed that companion friendships are of a ‘higher’ nature since, unlike romantic love, they are not tethered to bodily passion, causing them to be more conducive to virtue. C.S. Lewis claims that friends are absorbed in a common interest, whereas lovers are absorbed in each other. In this essay, I will examine what I consider to be certain flaws in this assumption. I will argue that eros permeates both types of relationships which makes it difficult to distinguish between the two. Furthermore, I will argue that companion friends are not only absorbed in a common interest, but are intricately absorbed in each other due to the dynamic combination of mutual self-disclosure, reflection, and interpretation of each other. C.S. Lewis in The Four Loves (1960) claims that when we refer to ‘all our friends’ we are usually referring to acquaintances and people who are valuable to us in a utility sense. These types of friendship form what he terms the ‘matrix’ of friendship, serving to bind society together into a functioning whole (77). This perspective mirrors Aristotle, who, in the Nichomachean Ethics, refers to philia as the quality of ‘goodwill’ in our relations which is crucial for the wellbeing of society. Aristotole sees philia as a good in its own right and, like other Greek philosophers of the time, does not reduce it to one particular category, but extends the term to include all forms of relationships, including romantic love. Lewis expresses this same broad view and is thus careful to point out that everyday, acquaintance/ utility-based friendships, should not be reduced to a ‘lesser’ form. He writes: ‘We do not disparage silver by distinguishing it from gold’ (Lewis, 1960, 77). However, Lewis, like Aristotle, does distinguish a form of friendship which, he believes, is more conducive to virtue; a type where each party sees the mirrored image of their own character and disposition. For Lewis, ‘character’ friendships such as these come about via the medium of a common interest, or passion. According to Lewis, this sort of friendship arises when two acquaintances in a group encounter a moment where each is stunned to find the other shares the same kinds of thoughts, interests and views as themselves. A kindred spirit is found, and a deep friendship is forged upon the strength of a ‘shared vision’ which sets the two apart from the group (Lewis, 1960, 78). Lewis goes on to distinguish this kind of friendship from romantic love in a language which is, ironically, very romantic in its tone. He speaks of the shared passion of friendship in terms of it being a ‘journey’ which must always be ‘about something’: ‘We picture lovers face to face but friends side by side; their eyes look ahead’ (Lewis, 1960, 79). Furthermore, he describes eros as having ‘naked bodies’ whereas friendship ‘naked personalities’ (Lewis, 1960, 84). Lewis’ description of friendship in terms of ‘naked personalities’ versus romantic love’s ‘naked bodies’ naturally suggests that what separates the two is sexual intimacy, a common assumption among academics. Immanuel Kant certainly agreed. He writes: ‘Sexual love brings with it an entirely new constellation of emotions, among which is the sheer delight in the body of another person which sets it apart from friendship’ (Kant in Lamb, 1997, 131). However, many academics point out certain flaws in the way sexual involvement is used to distinguish friendship from romantic love. This in turn leads us to the questioning of academic distinctions between types of love. Mark Vernon (2005) in The Philosophy of Friendship draws attention to how the lines which separate romantic love and friendship are often obscure, giving rise to the notion that friendship is not as different to romantic love as one might think. Vernon quotes from a letter by Montaigne to his friend Etienne la Boetie: ‘Take me and all I have, give me but your love, my dear friend. Tuesday is longed for by me and nights and days move a tedious pace till I am near you’ (Montaigne in Vernon, 2005, 29). Contrary to Lewis’s claim that friends are strictly absorbed in a common interest as opposed to each other, this portrait of friendship sees two friends expressing feelings that seem to mirror romantic love to a remarkable degree. Montaigne appears to be completely absorbed in his friend. In fact, Montaigne believed that the highest form of friendship involved a perfect fusion between two people. However, Lewis might argue here that this sort of longing for the other arises from the urge to re-engage the shared passion one has with ones ‘kindred spirit’, rather than a love which resembles romance with its erotic undertones. However, the examples of eros crossing the boundaries into friendship are many. C.D.C. Reeves points out Kierkegaard’s claim that eros and philia are ‘involuntary feelings ignited by the beloved’s physical, psychological qualities’ (Reeves, 2005, 4). Lewis himself admitted that the moment a man and a woman find that they have a ‘shared interest’, erotic love arises almost immediately (Lewis, 1960, 79). And, of course reductionists such as Freud claimed that all types of love have their origin in sexual impulses. This would seem to contradicts Lewis’ claim that there is nothing ‘throaty’ in Friendship; nothing to ‘quicken the pulse’, as he puts it (Lewis, 1960, 79). Moreover, it is common experience that many of the emotions associated with romantic love, such as a heightened feeling of affection, along with jealousy, and, sometimes hatred, are also common to friendship. In light of this, perhaps it would be fair to claim that companion friends are not only absorbed in a common interest, but also in each other in a way that is not very different to romantic love; that many aspects of eros seep into each category. Perhaps Mark Vernon puts it best by likening eros to the sand in the oyster’s shell around which ‘a smooth, lustrous coating of friendship may form’ (Vernon, 2005, 35). This analogy to some extent parallels Plato’s theory in Symposium where the journey of eros begins on the lower rungs of loves ladder (such as the loving of particular bodies) and ends with the ultimate love - the union with the Forms; with Beauty itself. Accordingly, Vernon concludes that the best kind of friendship is where the erotic element has been sublimated into ‘a shared passion for life’ (Vernon, 2005, 35). The idea of an undercurrent of erotic possibility running through friendship indicates there is a type of love in romantic relationships and companion friendship which is the same; the big difference being that in romantic relationships this love is expressed through sexual involvement, whereas in companion friendship this type of love must seek other means of expression. Lawrence Thomas (1989) draws attention to the fact that sexual involvement is not necessarily an indication of romantic love, especially in modern society where sex is often treated as more of a commodity, rather than something which cements ones deep love for another human being. Thomas believes that a better indication of the union between two people is found in the concept of ‘nurturing touching’. This is because ‘nurturing touching’ is not necessarily motivated by sexual desire, nor is it restricted to one type of relationship - but rather, it is an act which carries a variety of feelings and expressions all of which are governed by a sincere care for the other (124). Consequently, it enriches all types of relationships. Thomas scrutinises how society deems male-female romantic relationships to be the peak of union between individuals which causes ‘nurturing touching’ to find its fullest expression there. Society’s focus on romantic love causes people to feel inhibited about expressing ‘nurturing touching’ in other types of relationships, particularly in relationships between men (Thomas, 1989, 125). For Thomas, this ought not to be the case since it is conceptually possible for ‘nurturing touching’ to be equally expressed in all human relationships, causing the barriers between romantic love and companion friendship to collapse. He makes a good point. In countries such as India, where open physical expression between men and women is frowned upon, nurturing touching takes place quite openly in the streets with men holding hands and stroking each other affectionately. Moreover, it is common knowledge that in Arabic cultures men kiss upon greeting. Yet, some would argue that this would not be the case if these societies allowed open expression between men and woman. It does, however, give evidence to the idea of eros permeating all relationships. What Thomas is suggesting here is that if (in an ideal world) you were asked at a dinner party if you were in relationship, you should be able to say yes, if indeed you are in a relationship where ‘nurturing touching’ takes place. Hence, in contrast of Thomas’s stance, Lewis’s claim that friends are not absorbed in each other seems ill-conceived. However, there are many more ways in which friends can be said to be absorbed in each other; ways which may not necessarily be defined by undercurrents of eros or ‘nurturing touching’. Lewis claims that friends ‘meet like sovereign princes of independent states…freed from contexts’ (Lewis, 1960, 83). He argues that friends are not interested in revealing details about each others private affairs since this detracts from the ‘common interest’. However, Thomas contests this view. He claims that mutual self-disclosure of private information (‘secrets’) is absolutely vital in cementing the intimacy between companion friends. This is because such disclosure facilitates openness and vulnerability. If we drop our social guard and reveal intimate secrets to another, it signifies that we trust them. This allows a deeper relationship to flourish. However, Thomas believes that we must be discerning in how much we reveal of ourselves in public. This is because a person who reveals secrets to all and sundry is not a person who would make a good friend since they leave nothing secret for the other to be privy to. Furthermore, they would not be the sort of person one would be inclined to entrust with their private information (Thomas, 1989, 105). However, according to Dean Cocking and Jeanette Kennett, the sharing of secrets is not in itself significant to friendship. Dean Cocking and Jeanette Kennett (1998) claim that the disclosure of private information does not, in itself, indicate intimacy (518). For example, men are known to share intimate details of their sexual encounters with relative strangers. In fact, they claim that the revealing of secrets may in fact disrupt friendship. For instance, if a man were to reveal to his companion friend a fetish for women’s clothes, there is a fair chance this would cause a disturbing sense of embarrassment in the friendship. As a result, Cocking and Kennett would seem to support Lewis’s stance that friends are not interested in absorbing themselves in the personal details of the other. Yet this is not quite true. What Cocking and Kennett are saying is that the sharing of secrets is the outcome of something much deeper in friendship. For what is at stake here is not the nature of the private information in itself, but rather the fact that a friend chooses to reveal to the other what they value (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 518). In this way, Cocking and Kennett claim that sharing personal information such as a marriage break up is significant to friendship. This is because it shows that the friend places a very high value on the ‘hopes and concerns that [they] share with each other’ (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 519). Cocking and Kennett go on to claim that what matters in companion friendship is not so much the ‘shared interest’, but rather, the way in which friends are ‘responsive to [their] interests being directed by each other’ (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 508). But before examining what this means, it is first important to look at two other concepts that tie into this; the concepts of ‘mirroring’ and ‘drawing’. Lewis claims that “friendship is born at that moment when one man says to another: ‘What! You too? I thought that no one but myself’” (Lewis, 1960, 77). Here we have one person astounded to see their own point of view and qualities mirrored in another. Hence it could be argued that this sort of friendship is grounded in narcissism.(Aristotle believed that such friendships were an extension of self; Kant also held to the ‘mirroring’ view in terms of ‘character’ friends mirroring each others virtues.) However, Cocking and Kennett believe that this ‘mirroring’ concept of friendship is far too shallow. Contrary to Lewis, Cocking and Kennett claim that the mirroring of ones own traits in another is not what cements intimacy in a friendship. They claim that it is not the ‘shared interest’, nor the seeing of our selves in the other that is important, but rather our willingness to be mutually ‘drawn’ by the other (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 508). Hence they provide the analogy of a portrait painter which, in their view, better illustrates the dynamic nature of friendship. In this analogy the friend is not so much attempting to see themselves in the other, but is rather attempting to ‘draw’ their own version of the other, depicting them in a fresh way. They claim that the mutuality and reciprocity of this ‘drawing’ process enriches both parties. Consequently, Cocking and Kennett claim that it is not so much a case of seeing oneself in the other that shapes friendship, but the seeing oneself through the eyes of the other (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 509). This dynamic take on the nature of friendship challenges Lewis’ concept. Here, we find the two parties deeply absorbed in the other. Furthermore, Cocking and Kennett show how friends are not necessarily engrossed in an overarching ‘common interest’ in the way Lewis seems to suggest. By contrast, friends often take delight in the other person’s interests, even when such interests are not ‘common’ to their own, such as the example they provide of one friend who does not like ballet taking delight in ballet simply because the other friend loves it (Cocking and Kennett, 1998, 504). By this view, friends are very much shaped by the other person, modifying themselves in accordance with the others interpretation I have attempted to highlight some of the discrepancies in the way that romantic love is defined as a distinct category to friendship. The overlapping characteristics of both types, such as the all-pervading, often ambiguous, presence of eros, along with the concepts of ‘nurturing touching’ and mutual self disclosure and intimacy, suggests that lovers and friends function in similar ways. Nevertheless, the question of whether there are clearly defined ‘types’ of love and friendship, which can be separated into specific academic categories, is likely to produce much debate for years to come. References C.S. Lewis (1960) The Four Loves. London: Geoffrey Bles. CDC Reeves (2005) Love’s Confusions. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Roger E. Lamb (1997) Love Analyzed. Boulder: Westview Press. Mark Vernon (2005) The Philosophy of Friendship: New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Lawrence Thomas (1989) ‘An Account of Friendship [and Other Loves]’, selections from Living Morally: A Psychology of Moral Character: Philadelphia: Temple University Press. Dean Cocking and Jeanette Kennett (1998) ‘Friendship and the Self’, Ethics, Vol.108 pp.502-27