pdf - eMOTION! REPORTS.com

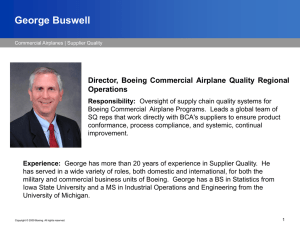

advertisement