Key Thinker Benjamin Franklin

advertisement

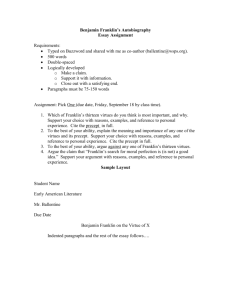

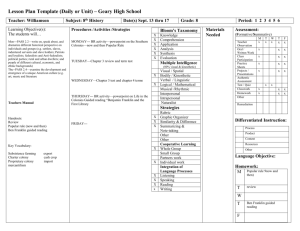

Benjamin Franklin (January 17 [O.S. January 6] 1706 – April 17, 1790) was one of the most important Founding Fathers of the United States. He was a leading author, political theorist, politician, printer, scientist, inventor, civic activist, and diplomat. As a scientist he was a major figure in the history of physics for his discoveries and theories regarding electricity. As a political writer and activist he, more than anyone, invented the idea of an American nation, and as a diplomat during the American Revolution, he secured the French alliance that helped to make independence possible. Franklin was famous for his curiosity, his writings (popular, political and scientific), his inventions, and his diversity of interests. As a leader of the Enlightenment, he gained the recognition of scientists and intellectuals across Europe. An agent in London before the Revolution, and Minister to France during the war, he, more than anyone else, defined and personified the new nation in the minds of Europe. His success in securing French military and financial aid was a great contributor to the American victory over Britain. He invented the lightning rod, bifocals, the iron furnace stove (also known as the Franklin stove), a carriage odometer and a musical instrument known as the armonica (a glass harmonica). With a talent for invention that transcended the mechanical, he also originated the tactic of raising funds by matching grants (to establish Philadelphia’s first hospital). He was an early proponent of colonial unity. Many historians hail him as the "First American," and he is also regarded as the only Founding Father who embodied the emerging American middle-class. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Franklin learned printing from his elder brother and became a newspaper editor, printer, and merchant in Philadelphia, becoming very wealthy. He spent many years in England and published the famous Poor Richard's Almanac and the Pennsylvania Gazette. He formed both the first public lending library and fire department in America as well as the Junto, a political discussion club. During this period he wrote in favor of paper money, against mercantilist policies such as the Iron Act of 1750, and also drafted, in 1754, the Albany Plan of Union, which would have created a continental legislature—demonstrating how early he conceived of the colonies as being naturally one political unit, and reflecting his more abstract attraction toward unity of all types as being valuable. Franklin became a national hero in America when he spearheaded the effort to have Parliament repeal the unpopular Stamp Act. An accomplished diplomat, he was widely admired among the French as American minister to Paris and was a major figure in the development of positive FrancoAmerican relations. From 1775 to 1776, Franklin was Postmaster General under the Continental Congress; during this period, he served on the committee of five that advised and spearheaded the drafting of the Declaration of Independence. From 1785 to 1788 he was President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. Toward the end of his life, he became one of the most prominent abolitionists among the Founders. He also played a major role in establishing the University of Pennsylvania, and Franklin and Marshall College. He was elected the first president of the American Philosophical Society, the oldest learned society in the United States, in 1769. Fluent in five languages, he is generally recognized as a polymath. Franklin as Social & Political Thinker: Influences and Background Many of the tendencies and habits of mind that later bore fruit in Franklin’s brilliant achievements can be found rooted in his family and youthful experiences. From a social perspective, the Franklin family represented a sub-species of independent British property owners who were not aristocrats, but middle-class farmers, that can be traced back to the 16th century Midlands (The word “franklin” itself from the Middle English “frankeleyn” meaning freeholder or freeman). A harsh nine-year printing apprenticeship to his older brother James, imposed on him late (in his twelfth year) and featuring severe autocracy and corporal discipline, certainly fostered his insistence on personal liberty, what Franklin called “…that aversion to arbitrary power that has stuck with me through my whole life.” He ran away before his term was expired. By mid-life, as a prosperous burgher of the times, he was a holder of two African slaves, one of whom was perennially running off; Franklin saw the analogy to his own behavior and viewed this with philosophical amusement. After a long period of deliberation over the nature of humanity, he concluded that no difference applied, freed his slaves, and became a firm advocate of abolition. During his youth in Boston, he saw, in functional terms, the continuum between the notions of the Puritan leadership (which he sometimes mocked as a young gadfly journalist) and the spirit of the Enlightenment in which he enlisted. Both Pilgrim’s Progress, the Puritan cultural artifact par excellence, and the essays of Enlightenment thinkers posited the concept that both individuals and humanity in general were moving forward and improving, based on a steady increase in the body of knowledge and in the wisdom that comes from overcoming adversity. The essence was practical and positivistic. The Mathers of Boston, the Puritan community’s church/civic leaders, set up neighborhood improvement associations, the first in the colonies, and concurrently, Daniel Defoe, Enlightenment intellectual across the sea in England, proposed community projects to upgrade sanitation, enhance traffic flow, and the like. Like the other advocates of republicanism, Franklin emphasized that the new republic could survive only if the people were virtuous in the sense of attention to civic duty and rejection of corruption. Indeed all his life he had been exploring the role of civic and personal virtue, as expressed in Poor Richard's aphorisms. Although Franklin's parents had intended for him to have a career in the church, Franklin became disillusioned with organized religion after discovering Deism, which can be defined as a religious philosophy and movement that derives the existence and nature of God from reason and personal experience. "I soon became a thorough Deist." (Autobiography, Chapter IV) He went on to attack Christian principles of free will and morality in a 1725 pamphlet, A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain. He consistently attacked religious dogma, arguing that morality was more dependent upon virtue and benevolent actions than on strict obedience to religious orthodoxy: "I think opinions should be judged by their influences and effects; and if a man holds none that tend to make him less virtuous or more vicious, it may be concluded that he holds none that are dangerous, which I hope is the case with me." A few years later, Franklin repudiated his 1725 pamphlet as an embarrassing "erratum"—possibly more for its lack of philosophical rigor than its conclusions. In 1790, just about a month before he died, Franklin wrote the following in a letter to Ezra Stiles, president of Yale, who had asked him his views on religion...: As to Jesus of Nazareth, my Opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the System of Morals and his Religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupt changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some Doubts as to his divinity; tho' it is a question I do not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and I think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble...." Like most Enlightenment intellectuals, Franklin separated virtue, morality, and faith from organized religion, although he felt that if religion in general grew weaker, morality, virtue, and society in general would also decline. Thus he wrote Thomas Paine, "If men are so wicked with religion, what would they be if without it?" Conversely, Franklin also expressed a modicum of skepticism toward reason, stating that it had its own form of abuse, namely rationalization, the capacity to justify what one desired, no matter what. Beliefs held, concepts advocated by Franklin It is historically apt that Benjamin Franklin founded the American Philosophical Society, because his primary tendency in thinking and in action, most likely rooted in his development as a scientist and inventor, was toward pragmatism in the ordinary sense. His speculative thinking, possibly influenced by personal intellectual exchanges with Emmanuel Kant and David Hume during his sojourns in England and France, can be viewed as an early tributary or precursor of philosophic pragmatism, the distinctly American school. Pragmatism per se originated in the late nineteenth century with Charles Sanders Peirce, who first stated the so-called pragmatic maxim.i The school came to fruition in the early twentiethcentury philosophies of William James and John Dewey. Most of the thinkers who describe themselves as pragmatists consider practical consequences or real effects to be vital components of both meaning and truth. Franklin himself has been labeled by at least one prominent historian as a “pragmatic visionary”—he thought big, in transformative sweeping terms and with no aversion to iconoclasm, but insisted on testing hypotheses in practice as soon as conditions made that fair and feasible. He applied this approach not only to the physical world and its mysteries (such as electricity or the Gulf Stream, two of his objects of inquiry), but to the nature and behavior of his fellow humans. For example, he very early adopted anti-sexist views, testing the antisexist advocacy found in his reading of Defoe against his own experience in a very creative way: as a teenaged printer/journalist he wrote pseudononymous political/social satire in the guise of a widow named Silence Dogood. The sometimes dismissive responses to her Franklincomposed letters to the editor were marked with ad hominem thinking; evidently the readers needed to know the age, gender, ethnicity, class status, and so on of an author before taking his/her arguments at face value, on their merits. (His working realization that women were of equal intellectual capacity as men, expressed in his subsequent proposals to educate girls, not only demonstrates his open, enlightened thinking, but, typical of Franklin, seems to have had the practical use of making him successful as a lover and man about town!) In another instance, in his last decade, as the Constitution was going through ratification and term limits compelled his retirement from presidentialii service to the State of Pennsylvania, he turned his attention to the unfair treatment of Native Americans and praised their cultures and ways in a manner that we might call cultural relativism today. He focused on the wisdom of their political organization: All their government is by the counsel or advice of the sages; there is no force, there are no prisons, no officers to compel obedience or inflict punishment. At council meetings the old men sat in the foremost ranks; when one of the old men rose to speak, everyone else observed a respectful silence. How different this is from the conduct of a polite British House of Commons, Franklin noted sardonically, where scarce a day passes without some confusion that makes the Speaker hoarse in calling to order. His essay also included a story in which a Christian missionary and an Indian leader of the Susquehanna exchanged creation myths; the Indian found a way to respect and incorporate the Judeo-Christian story of Genesis and the fall into his framework of belief, whereas the missionary proved to be a close-minded chauvinist, dismissing the Indian version in disgust. Beyond such vivid argumentation, Franklin took practical steps to assist the Wyandot chief Scotosh in raising concerns with the Congress about encroachment on tribal territory by surveyors. He even suggested to then Foreign Secretary (the term Secretary of State was adopted later) John Jay that Scotosh should be sponsored on an official trip to France, both to impress the French and to help the Indians gain a fuller appreciation of the power of our Revolutionary partner. Value of Unity/Strength in Numbers Famous for the pro-Revolutionary witticism, “If we don’t hang together, we shall all hang separately,” Franklin persistently worked for consensus and unified action in the civic and political domain. He first saw the value during the French and Indian War, when a number of the colonies’ inefficiencies in coordinating military action bore a heavy cost against a numerically inferior enemy. He saw them as lacking a unified planning and command structure and indulging in envy and senseless competition. The idea that became the Albany Plan of Union proposal, the first national federal model for the American colonies, was developed iteratively, with much input from colleagues, so that by the time the proposal was complete it already had many stakeholders who were already familiar with the reasoning, indeed recognized their own contributions, and so were ready to advocate. Franklin probably could have devised an excellent proposal on his own, but in a typical tactic, he orchestrated what we would call ‘buy-in’ today. Franklin and the Cosmopolitan Lineage Franklin was a son of the Enlightenment and a product of the British Empire of the eighteenth century, as one key colony created its own separate destiny. Would he be a cosmopolitan today? That is unclear; what is clear is that he was a great skeptic toward the alleged inferiority of other races, peoples, nations, and their ways. He echoed Hume in regarding no nation as “naturally” superior, nor indeed based in an a priori natural order.iii Humankind was diverse but equal in his view, and a matter of appreciation, even fascination. He believed fiercely in the uniting of peoples for the common good—their resources, their goodwill, their energies. He loved the new country he did so much to midwife and defend, and yet it is easy to imagine him transported in time, providing sage counsel to the establishment of the League of Nations or the United Nations or the next global effort to unify and provide the blessings of peace and justice to humankind, and husband the health of our home planet that he so zestfully studied. We are launching this site for our foundation with a name, “One World United & Virtuous,” that itself comes from a phrase of Franklin’s, extracted from his May 9, 1731 note, “Observations on my Reading History in Library”, which evidently arose from discussion in the Junto. Franklin did not use the term “One World”, but he did speak of a party of virtue in global terms, proposing ways that men and women of virtue could unite political efforts across national boundaries, for the common good. We close this profile with his words: That few in Public Affairs act from a mere View of the Good of their Country, Whatever they may pretend; and tho their Actings bring real Good to their Country’ Yet men primarily considered that their own and Their Country’s Interest was united, And did not act from a Principle of Benevolence. That fewer still in Public Affairs act with a view to the Good of Mankind. There seems to me at present to be great Occasion for raising an united Party of Virtue by forming the Virtuous and good Men of all Nations into a regular Body, to be governed by suitable and good and wise Rules, which good and wise Men may probably be more unanimous to their Obedience to, than common People are to common Laws. I at present think, that whoever attempts this aright, and is well qualified, cannot fail of pleasing God and of meeting with Success. Sources: Wikipedia biography; The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin, by H. W. Brands; The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, w/ introduction by Andrew S. Trees; Benjamin Franklin: An American Life, by Walter Isaacson; Letters of Benjamin Franklin, in http://franklinpapers.org/franklin/framedMorgan.jsp. i The pragmatic maxim, also known as the maxim of pragmatism or the maxim of pragmaticism, is a maxim of logic formulated by Charles Sanders Peirce. It was formulated as a reaction to metaphysical theories. Although Peirce does not use the term "pragmatic maxim," in the following description of the "first rule of reason," he expresses the same sentiment: Upon this first, and in one sense this sole, rule of reason, that in order to learn you must desire to learn, and in so desiring not be satisfied with what you already incline to think, there follows one corollary which itself deserves to be inscribed upon every wall of the city of philosophy: Do not block the way of inquiry. Although it is better to be methodical in our investigations, and to consider the economics of research, yet there is no positive sin against logic in 'trying' any theory which may come into our heads, so long as it is adopted in such a sense as to permit the investigation to go on unimpeded and undiscouraged. On the other hand, to set up a philosophy which barricades the road of further advance toward the truth is the one unpardonable offence in reasoning, as it is also the one to which metaphysicians have in all ages shown themselves the most addicted. ii iii equivalent of gubernatorial David Hume (1711-1776) was a skeptic, and although he was a complex and dedicated philosopher, he shared a political viewpoint with previous Enlightenment philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes (15881679) and John Locke (1632-1704). Specifically, Hume, at least to some extent, argued that religious and national hostilities that divided European society were based on unfounded beliefs; in effect, he argued they were not found in nature, but a creation of a particular time and place, and thus unworthy of mortal conflict. Thus Hume is often cited as being the philosopher who finally snuffed out nature as a standard for political existence. For instance, without Hume, Jean Jacques Rousseau’s (1712-1778) 'return' to nature would have not been so revolutionary, inventive and fascinating.