Working with deaf children and their communities worldwide

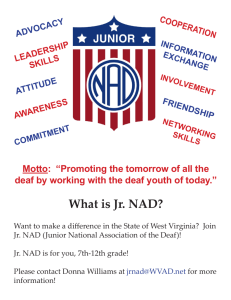

advertisement