Counterfeit Parts - Aerospace Industries Association

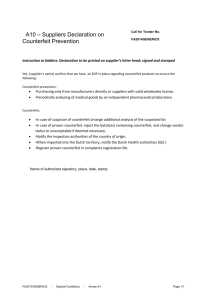

advertisement