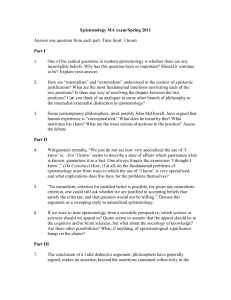

reformed epistemology

advertisement

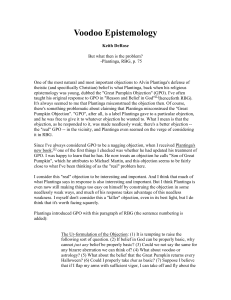

Kyle Worley Philosophy of Religion Fighting on Our Terms: Reformed Epistemology Christian philosophy for too long has had to cower at the demands of the “scientific, rational, reasonable philosophers” in terms of how we go about debating ideas. One of the major foundations of any given debate is going to be found in the existence of God. Countless philosophers over thousands of years have come up with reasons for the existence of God. Aquinas, Aristotle, and Anselm have all submitted different thoughts regarding God’s existence and placement in the universe. The point of this paper is neither to explicate natural theology arguments nor to somehow discredit these arguments or their importance in the scope of the study of God. Reformed epistemology seeks to show that “it is possible for religious beliefs to be entirely rational and fully justified even if there is no evidence supporting these beliefs” (Reason and Religious 109). This emerging idea is gaining steam in the Christian philosophical world and is causing ripples throughout all thinking. Reformed epistemology could be one of the great hopes of the Christian philosophical world. This new argument is being led by Christian philosophers such as Alvin Plantinga, Nicholas Wolterstorff, and William Alston. These philosophers are suggesting, based mostly on biblical theology and the ideas of reformers like John Calvin, that religious beliefs and faith are rational and justified even if there is no sensible evidence confirming these beliefs. It is quickly seen why this would cause ripples throughout the entire thinking world. Philosophers have long demanded that any belief must have strong foundations. This idea is referred to as strong or classical foundationalism. Classical foundationalism says that only “certain, well-established beliefs constitute the foundation…and nonbasic beliefs must be rightly related to the foundation, either based on or derived from” (Handout). They say that a basic belief must be self-evident, evident to the senses, and incorrigible. This mode of thinking has been and is still predominate in most academic settings. Plantiga, and other reformed epistemologists, are simply arguing that Christians must not meet these criteria to hold a rational and justified belief nor must they allow strong foundationalists set the parameters and basis for arguing cases such as God’s existence. To go deeper into the rabbit hole of strong foundationalism we must examine what follows from strong foundationalism, evidentialism. Wolterstorff states the evidentialist challenge in this way: “No religion is acceptable unless rational, and no religion is rational unless supported by evidence. That is the evidentialist challenge” (Reason and Religious 109). Reformed epistemology has strong concerns and disagreements towards both the strong foundationalism structure of thought and the evidentialism that emerges from that structure. Reformed epistemology begins with the idea set forward by Bavinck that “The so-called proofs are by no means the final grounds of our most certain conviction that God exists: This certainly is established only by faith; i.e., by the spontaneous testimony which forces itself upon us from every side.” Plantinga takes this foundation of certainty in God found only in and through faith and uses it as the foundation for structuring all of his arguments! This is unheard of in the philosophical world. It is completely counter what strong foundationalism supports. Reformed epistemology asserts that foundational to its structure is the belief and knowledge that “arguments of proofs are not, in general, the source of the believer’s confidence in God” (Plantiga 262). The first part of the title reformed epistemology gives light to many of the presuppositions that build the arguments proposed by Plantiga and others like him. John Calvin and those who follow in his wake would completely agree that divinitatis sensum and the testimony of the Holy Spirit provide all the grounds for a believer’s faith. This faith is rational and justified because of the illumination and revelation of God to an individual. The reformed argument for God’s revelation to man goes much deeper than this and is a beautiful picture of God and his relation to man. The reformed argumentation has had such a profound impact on my life that even in reading up on reformed epistemology my heart has been rekindled to break out my Institutes and let the words hit me again. I am sure that Plantiga feels the same way because his argumentation for epistemology finds so many of its roots in the reformed tradition. Another assertion made in reformed epistemology is that argument is not need for rational justification of a belief or set of beliefs. Plantinga says that “a believer is entirely within his epistemic right in believing that God has created the world, even if he has no argument at all for that conclusion” (Plantinga 262). Plantinga would argue with the backbone of Calvin that men everywhere testify to the existence of God in their felt inclination towards him either in questioning or supposing. They would also argue that men everywhere, school and unschooled, see the art of God because we live in the “Theatre of God.” In short reformed epistemology is heavily rooted in the reformed tradition, specifically the thought of John Calvin. Moving on from the roots of reformed epistemology it is important to establish that this structure of philosophy takes belief in God as basic. This would lead to the notion or underlying thought of a loose weak foundationalism. Weak foundationalism would be the only sort of foundationalism that reformed epistemology would connect with. Weak foundationalism will suggest that there is foundation, but different worldviews lead to different basic beliefs. Plantinga would agree with this to a point. By all means, Plantinga rejects classical foundationalism. Plantinga builds his “foundationalism,” if it must be called that on the concept of a noetic structure. A noetic structure is simply “the set of propositions he believes together with certain epistemic relations that hold among him and these propositions” (Plantinga 265). This noetic structure for reformed epistemologists is found beneath any “foundation.” An account of a noetic structure would begin with the definition on one’s basic and non-basic beliefs, move to an index of degree of belief (the strength with which we hold to a certain belief, and ending with a depth of ingression (beliefs that are “on the periphery of one’s noetic structure”). Plantinga’s view of a “rational noetic structure” is simply to “do the right thing with respect to one’s believings” (Plantinga 266-267). The concept of noetic structure argued by Plantinga advances the idea that any “foundations” for one’s beliefs are based on worldviews or presuppositions held by that person. This leads to Plantinga’s argument that in a rational noetic structure some beliefs will be independent and not based on any other beliefs. It is these beliefs that we call foundations. These foundations must be certain. In closing I want to examine two more aspects of the reformed argument. In terms of rejecting classical foundationalism, the rejection is an outright one. Plantinga would argue alongside Calvin that “one can rationally accept belief in God as basic; he also claims that one can know that God exists even if he has no argument, even if he does not believe on the basis of other propositions” (Plantinga 269). This flies right in the face of any classical foundationalists for it goes a step further then just a rational belief and suggests that a believer can know, for a truth or fact that God exists even though he has no argument or underlying basis built on other beliefs. Coming out of this great argument I want to bring up the Great Pumpkin Objection. Simply put, the objection raised is if belief in God is properly basic, why can’t just any belief by properly basic? Any bizarre belief could be basic? Plantinga says certainly not. Plantinga argues that ideas such as the great pumpkin or any such bizarre objection is unwarranted and not even the same as an argument for God. Reformed epistemology is any many ways restructuring the way philosophy is being done both christianly and secularly. It is empowering Christian philosophers across the world to stand and embrace their faith and make it their epistemic foundation. By leveling the philosophical playing field we can expect that Christian philosophy will rise and we will finally be able to debate and argue with others on our terms.