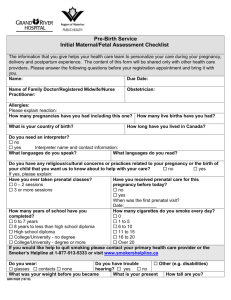

Multicultural Clinical Support Resource

advertisement