1 FORDHAM CENTER ON RELIGION AND CULTURE THE

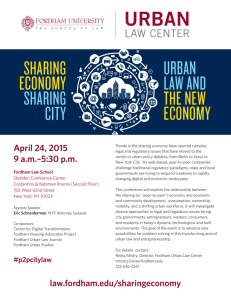

advertisement