1-Gregory M Eirich.pmd

advertisement

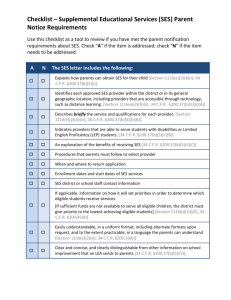

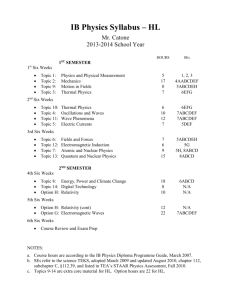

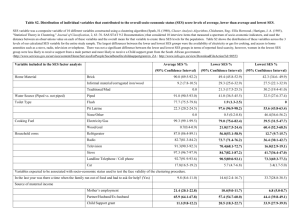

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY VOLUME 37, NUMBER 2, AUTUMN 2011 PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL INEQUALITY IN THE UNITED STATES GREGORY M. EIRICH Columbia University A small but important literature has theorized that parental socioeconomic status (SES) affects sibling educational inequality. First, this paper confirms previous suggestive evidence that as parental SES increases in the United States, sibling educational inequality decreases. A child from high SES parents is more likely to have a sibling with a similar (relative) schooling level than a low SES child, who will be further away educationally from his or her sibling. Second, this paper casts doubt on the literature’s hypothesized causal mechanisms for this result. Using a simple simulation approach, this paper illustrates that the strong negative association between parental SES and sibling educational inequality does not appear to be due to any active parental investment decisions to steer (or balance) their children’s schooling trajectories, as the literature has previously hypothesized; instead, it is likely due to structural forces outside of parental control. This paper suggests some possible structural forces behind the patterns uncovered. A small number of scholars have examined if parental socioeconomic status (SES) affects educational stratification dynamics among multiple children within the same family (Becker 1981; Behrman et al. 1995; Conley 2004; Gaviria 2002; Dahan & Gaviria 2003). Relying on the parental investment paradigm (begun by Becker & Tomes 1976; 1986), they investigate if parents invest in their various children’s educations differently depending on the family’s total budget. Specifically, they ask: Because of SES differences between families, do some families produce children virtually identical on educational attainment (low sibling educational inequality), while other families produce very educationallydifferent children (high sibling educational inequality)? Tentative evidence to date suggests that increased parental SES reduces the amount of educational inequality between siblings in the United States 184 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY (Conley 2004; Gaviria 2002). A child from high SES parents is more likely to have a sibling with a similar (relative) schooling level than a low SES child, who is further away educationally from his or her sibling. While this result contradicts Becker & Tomes’ original predictions, researchers have explained it, by arguing either: (a) given extensive resources, high SES parents actively compensate for ability disparities between their children by over-investing in the less able siblings to raise them to the level of the more able ones, thereby lowering sibling inequality; or (b) low SES parents, given a budget constraint, are forced to actively exacerbate the children’s ability disparities by withholding investment in the less able siblings in order to provide full educational funding for the most able ones, thus increasing sibling inequality; or (c) both processes are at work. These theories have been applied both to the U. S. and internationally (for examples of the latter, see Dahan & Gaviria (2003) on Latin America and Chu et al. 2008 on Taiwan). Using a nationally representative sample of American siblings, I first aim to confirm that sibling educational inequality is lower among children of high SES parents. I then use a simple simulation – which involves comparing the educational inequality between actual siblings to the inequality between pseudo-siblings with virtually identical SES backgrounds, but with no actual kinship relation to each other – to test for the presence of an active parental investment process, which has been assumed by previous researchers. I then consider a more social-structural process as an alternative explanation (Raftery & Hout 1993; Hout & DiPrete 2006). There may be less educational inequality among high SES siblings simply because there is less educational inequality among all high SES children in general, while there is greater educational inequality among low SES children (and by extension, among low SES siblings). This fact – combined with a “threshold” model (Breen & Goldthorpe 1997), where parents try to prevent children from falling below their own SES position, yet are not as concerned about how high children rise up the education ladder – could produce the same results, without having to posit differential parental investment decisions. The simulation technique allows us to adjudicate between the typical economic explanation and this new one. By testing the parental investment perspective, this paper contributes to a chorus of sociologists, especially economic sociologists, who argue economic models often rest on unrealistic notions of hyper-rationality of agents (for a review, see Rona-Tas & Gabay 2007). Many highlight PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 185 how the overall structure of socioeconomic opportunity seeps into our most intimate relationships, including among siblings (Conley 2004; Zelizer 2005). My research indicates that interpreting findings through the individualistic and homo economicus lens of parental investment models may be uncalled for, when models linked to the educational opportunity structure as a whole may produce more credible results. By proposing multiple siblings from the same family as a new unit of analysis for stratification, this paper also advances our thinking on siblings. Ever since Blau & Duncan (1967), research indicates that siblings impact individuals’ educations through their sheer number, decreasing educational attainment as sibship size grows (Steelman et al. 2002). I test a relational model of educational attainment instead (like Conley 2004; Heflin & Pattillo 2006), where families should be evaluated not only regarding one child’s educational attainment, but regarding the reliability of producing that level of education in multiple children (Scarr & Grajek 1982). Reliability is crucial since one sibling is not easily replaceable for another; the correlation between the educational attainments of siblings is surprisingly low, only 0.5 (Solon et al. 2000). THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK Parental SES, Parental Investment Decisions and Sibling Inequality The small literature on parental investment behaviors and sibling inequality has produced a number of conflicting theories, all tied to Becker & Tomes (1976; 1986). They originally predicted that as parental SES increases, educational inequality among siblings will grow, where “SES” is narrowly construed as parents’ wealth and income. On the one hand, high SES parents will invest in more scholarly siblings up to the marginal rate of return on that educational investment, but will withhold investment in weaker siblings, due to their predicted lower return on parental wealth. Parents want their children to have equal total living standards ultimately, and so high SES parents will compensate less endowed children with inter vivos transfers and bequests later in life to bring them in line with more endowed children who achieved their living standard via advanced schooling. They predict: Siblings from low SES parents, on the other hand, will have more educational equality because their parents will recognize the family does not have the wealth holdings required to compensate the less endowed siblings with financial transfers and bequests later in life, to bring them in line with the child who received more initial investments. Low SES parents will make suboptimal but 186 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY equal investments in each child’s human capital, rather than giving more to some based on their abilities. They predict that as parental SES increases, educational inequality among siblings will grow. No evidence has been found for this hypothesis. Given lack of empirical support, two challenges have been made to this theory, which either singly or in combination, would predict that as parental SES increases, educational inequality between siblings decreases. One theory argues, high SES parents will actively work to minimize the human capital differences between their children. Behrman et al. (1995) developed the “compensating hypothesis,” where parents compensate for ability deficits in lesser endowed siblings, trying to even out human capital levels, so that eventual earnings levels will be more equal, mitigating the need for inter vivos transfers to less able children later in life. Parents, when faced with children heading in opposite educational directions, will try to raise laggard children up to some family goal by over-supporting the weaker siblings, even if those investments are suboptimal in Becker’s sense (Behrman et al. 1995). Conley speculates that “when parents have lots of ‘class’ resources to go around—time, money, social connections— children often are more alike since parents don’t have to ‘choose’ between them and can actively compensate for disparities in skill or pluck. (Think of the Kennedys or the Bushes.)” (Conley 2004: 6). The other theory argues that low SES conditions – i.e., having “limited opportunities and resources” – “may elicit parenting strategies that accentuate sibling differences by directing family resources to the betterendowed siblings” (Conley & Glauber 2008: pp. TBD). Conley’s (2004) hypothesis is that since low SES families face budgetary constraints, they are forced to choose between their desire to efficiently allocate their resources and their desire to aid all their children in achieving equivalent education levels; and they will choose to efficiently invest in the better endowed siblings. Dahan & Gaviria (2003) have also developed this theory in much the same way, and tested it using data from multiple Latin American countries, finding some support. Using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the Health and Retirement Survey (HRS), Gaviria (2002) finds that siblings from families with high wealth have lower educational inequality than siblings from families with little to no wealth. In Conley’s (2004) interviews, he finds evidence that low SES parents make investment choices in favor of one or two siblings at the expense of other less academically-oriented ones. In quantitative work (also using the PSID), Conley & Glauber PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 187 (2008) find weak – but directionally correct – differences between high SES and low SES families. The sibling education correlation for children whose mother had 13 years of education or less (his proxy for low SES) is lower than for children whose mother had more than 13 years of education. Lastly, using the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), Mazumder (2004) finds that siblings from above-average income families have slightly higher educational correlations compared with siblings from below-average income families. Overall, increased parental SES ought to reduce educational inequality between siblings. Yet this result could occur either because of active parental differential investment (as the scholars above argue, but do not directly demonstrate) or because of an alternate theory (outlined below). Social Structure, Parental SES and Sibling Inequality A social-structural explanation for the above results is quite plausible if two conditions are met: (1) children of high SES parents fall into a tighter “landing area” of educational destinations, compared to children of low SES parents (Raftery & Hout 1993; Hout & DiPrete 2006); and (2) sibling inequality reflects the overall educational distribution of children from the same SES, such that a narrow educational distribution for high SES children translates into low educational inequality among high SES siblings, precisely because they are high SES children – and vice versa for low SES children. Figure 1 illustrates this idea. In this hypothetical example, the box-and-whisker plots indicate that low SES children have a very wide range of ultimate educational attainments, with middle SES children having a less wide range of such attainments, and high SES children having a very narrow range of ultimate amounts of schooling; this is Condition 1. The arrows indicate the possible correspondence between the macro-level educational inequality found within each SES class and the micro-level inequality found among a pair of siblings from that SES class; this is Condition 2. There are two possible reasons why the micro-level inequality found among a pair of siblings from a given SES class would mirror the amount of macro-level educational inequality found within that SES class. One, a threshold model could produce the observed pattern. Parents try to prevent children from falling below their own SES position yet are less concerned about how high children rise up the education distribution (Breen & Goldthorpe 1997). It is possible that ceiling and floor effects are stronger for children of high SES parents than for low 188 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Figure 1: Hypothetical Correspondence Between SES-Specific Overall Educational Inequality and Inequality Among Siblings of the Same SES Class Overall (PopulationLevel) Educational Distribution, by SES Sibling Educational Inequality, by SES High SES High SES Middle SES Middle SES Low SES Low SES SES ones, meaning that high SES children typically fall into a narrower range of educational attainment levels than children from low SES families (Hout & DiPrete 2006; Mare & Chen 1986). Low SES parents, since their expected “floor” is low to begin with, can push their children to rise over a wider range of educational levels more easily. This explanation differs from the parental investment model because the education distribution itself, which is external to parental control, determines the amount of sibling educational inequality; not individual parental assessments of, and differential investments in, their portfolio of children, made in light of the overall family budget. Parents can invest however much they think is necessary to make sure their children do not fall behind, but those investments will translate into lower inequality among high SES siblings, since their likely ultimate educational placements were less unequal than for low SES children to begin with. PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 189 Higher educational inequality among children from low SES families may also be driven by a second reason: upward mobility public policies directed to low SES children. They often provide opportunities for only a limited number of low SES children to move up, and not all siblings from the same family can access the limited number opportunities. Conley & Glauber (2008) note that “society writ large could generate a larger variance in outcomes for disadvantaged families through a process of tokenism that generates apparently random influences when viewed at the family level” (pp. TBD). Some low SES children are tapped for special free programs (e.g., Prep for Prep, charter schools, after-school programs) and rise dramatically within the education system as a result, while their siblings because of bad luck, bad timing or lower initial apparent potential, did not get access to the same types of programs and attain lower levels of schooling. Under this scenario, if the social policy consequences from the low SES educational distribution could be accounted for, the greater sibling distance amongst low SES children than amongst high SES children would diminish. DATA AND METHODS Sample I use a nationally-representative sample of siblings from the General Social Survey’s (1994) module, the Study of American Families (SAF), fielded by Robert M. Hauser and Robert D. Mare; the response rates are quite high with the GSS in general, approximately 71 per cent. Beyond the usual battery of questions asked in the GSS, they asked the respondent for information on one randomly-chosen sibling (for an introduction to the SAF, see Hauser & Mare 1994).1 Therefore, my analyses will apply to two siblings per family. I limit my analysis to families where: both siblings are full siblings (to ensure they had the same parents) and both are 25 years of age or older (to ensure they have completed their educations). I use GSS-provided sample weights in all analyses, making my results representative of the non-institutionalized, civilian, Englishspeaking adult United States population in 1994. I utilize the following variables in my analyses. 1. Dependent Variable. Sibling Educational Inequality. Following Gaviria (2002), I use a scale-free measure of educational inequality (Allison 1978; Sørensen 2002), the coefficient of variation (CV), which is calculated as follows: CV = (σi/µi)*100, where σi is the standard deviation of the 190 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY ith family’s educations (i.e., generated from both siblings), divided by µi, the ith family’s mean educational attainment (i.e., generated from both siblings). Individual educational attainment is the number of years of formal schooling reported by the GSS respondents about themselves and their siblings, top-coded to 20 years. Without direct observation of parental behaviors toward their children, most researchers rely on total years of education as “an indirect, but behavioral measure” of parental investment patterns (Hopcroft 2005: 1116). In fact, Kim (2005) finds that each $1,000 educational contribution from parents translates into a 0.067 increase in the total number of years of schooling for their children. Table 1 Summary Statistics (Unweighted), Full Siblings, Aged 25 or Older Coefficient of Variation, Sibling Educational Attainments Parental SES Total Number of Siblings Age Difference, Pair Average Age, Pair Mixed Sex Pair African-American Average Educational Attainment, Pair Obs. Mean St. Dev. 837 837 837 837 837 837 837 837 10.59 0.04 3.56 4.98 45.79 0.50 0.10 13.56 12.95 1.36 2.61 3.79 13.78 2.46 2. Independent Variable. Socioeconomic Status (SES). SES refers to the resources that individuals accumulate and the lifestyles they embody, given their joint positions in the education, labor, marriage and property markets (Weber 1978). My proxy for SES is generated from the first factor score from a principal components analyses of three measures: (1) the highest total number of years of schooling attained by the respondent’s parents, whether mother or father, which is generally found to be the single best predictor of children’s educational attainment (Blake 1989); (2) the highest prestige ranking score of either parent’s occupation when the respondent was 16 years of age, which is indicative of “permanent income” and of the family’s resource-generating capacity (Blau & Duncan 1967; Goldthorpe 1996); and (3) a 5-point Lickert item asking respondents, compared with American families in general, how large was their family’s income when they were age 16, ranging from far below average to far above average. The Eigenvalue on the first principal component is above 1 (1.87) and accounts for most of the total variance (62.32%). PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 191 3. Control Variables. Total Number of Siblings. The total number of siblings that the respondent and sibling have, including step-siblings, half-siblings and adopted siblings. Sibling Age Difference. The number of years of age separating the two siblings in the pair.3 In addition to the age difference, I include the Sibling Average Age (of the pair) to account for positive drifts over time in educational attainment or other cohort effects (Hauser & Sewell 1985). Sibling Sex Mix. I constructed an indicator variable for whether the pair was mixed-sex or same-sex (where “same-sex” means either two males or two females). Race. I included an indicator variable for whether the respondents are African-American, or not. Techniques of Analysis To test my hypotheses, I rely on two techniques. 1. OLS Regression. In order to assess the relationship between parental SES and sibling educational inequality, I run an OLS regression, represented as follows: Yi = α + β1Xi + β2Zi + ε, where Yi is a measure of sibling educational inequality, Xi is the SES of the siblings’ parents, and Zi is a vector of other characteristics of the family or of the sibling pair. 2. Simulation. To adjudicate between parental investment theories and a social-structural one, I run a simple simulation, which is implemented as follows. I ranked all families according to parental SES. I then gave every family a new sibling drawn from the family right above it.2 In this way, I made pseudo-siblings, with virtually identical SES backgrounds, but with no real kin relation to each other. I then reran the above OLS regression equation on this sample of pseudo-siblings, and compared the resulting estimates on the parental SES coefficient to the original ones obtained above. If parental investment decisions are really responsible for the SES gradient on sibling inequality, when I rerun the regression on pseudo-siblings, the coefficient on parental SES should be greatly attenuated (close to zero) because I removed the ability for parents to differentially invest in their children. After all, in the simulated world, parents cannot assess both children’s abilities and long-term prospects, since they only know one child, nor can they decide how to invest across both children, since they only actually invested in one of the two children. If parents could do nothing to affect the inequality of “fake” siblings, but the fact that the coefficient on parental SES is the same as in the original 192 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY OLS model, this means that something other than parental actions must be driving the relationship. To date I am not aware of other researchers who have used such an approach. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION As Table 1 indicates, the mean sibling coefficient of variation on education in the population is 10.59. The average sibling pair’s standard deviation in education is about 10.6 per cent the size of their mean educational attainment level. That is a meaningful amount to differ on; it translates into almost two years difference in years of schooling for the average sibling pair. Our first question is: Does the coefficient of variation vary by the SES of the family? The results from the multivariate OLS models directly answer this question and they are conclusive. Table 2 shows that as parental SES increases, the amount of sibling educational inequality decreases noticeably (b=–1.50, p<.01). The magnitude of the SES factor is quite large, where the Beta (standardized) estimate is -0.16; for every one standard deviation increase in parental SES, sibling inequality is reduced by about a sixth of a standard deviation. This result is consistent with either the “low SES reinforcement of differences” hypothesis or the “high SES compensating” hypothesis. This result is, however, also consistent with a social-structural perspective, where there are societywide processes that spread low SES siblings further apart from each other than high SES siblings. Also of note in the model, mixed-sex siblings are further apart educationally (b=1.85, p<.05). This is consistent with historical evidence that boys were given greater educational resources than girls until recently, even within the same families (Buchmann & DiPrete 2006). The average age of the pair is also positively associated (b=0.06, p<.10) with educational inequality, which is consistent with the life-course standardization model of historical change, where siblings are closer educationally in recent decades compared with earlier in the century (Shanahan 2000). In supplementary analyses, I find that most of the educational inequality among low SES siblings is focused on differences below high school graduation levels, and is not found in one sibling “crossing over” to get at least some college education (results available upon request). By running a simple simulation, it is possible to rule out some proposed mechanisms that cannot be behind the strong negative PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 193 Table 2 OLS Regression for Inequality in Educational Attainment among Full Siblings, Aged 25 and Older Parental SES Total Number of Siblings Age Difference, Pair Average Age, Pair Same Sex Pair (reference) Mixed Sex Pair All Other Races/Ethnicities (reference) African-American Constant Observations (Pairs) Adjusted R2 Coeff. Beta -1.50** (0.44) 0.31 (0.21) 0.02 (0.12) 0.06+ (0.03) 1.85* (0.89) -1.74 (2.02) 5.94** (2.04) 837 0.042 -0.16 0.06 0.01 0.06 0.07 -0.04 • Robust standard errors in parentheses. Data weighted by sample weights provided by GSS. **p<.01 * p<.05 + p<.10 (two-tailed) association between parental SES and sibling educational inequality. Recall that I ranked all families by SES, and then gave every family a new sibling drawn from the family right above it. I made pseudo-siblings, with virtually identical SES backgrounds, but with no actual kinship relation to each other. I then reran the original OLS regression and compared the new parental SES coefficient to the original one. This process of shifting siblings down one family does introduce tremendous randomization; indeed, the “fake” siblings only have an educational correlation of 0.23 vs. the real siblings of 0.48. Does it make a difference in terms of the relationship between parental SES and sibling inequality? As Table 3 shows, it does not make a difference. The coefficients on parent SES in the real sibling model and the pseudosibling model are statistically indistinguishable: b=-1.61 for the real siblings, and b=–2.30 for the pseudo-siblings. The t-test for a difference between these two coefficients yields a t-statistic of -0.75, p=0.45 (twotailed).4 Their Betas are also very similar: 0.17 for the real siblings and 194 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Table 3 OLS Regression for Inequality in Educational Attainment among Real (Full) Siblings vs. Pseudo-Siblings (Simulation), Aged 25 and Older Real Siblings Pseudo-Siblings (Simulation) Coeff. Beta Coeff. Beta -1.61** (0.46) -0.17 -2.30 (0.38) -0.20 Age Difference, Pair 0.05 (0.12) 0.01 0.03 (0.05) 0.02 Average Age, Pair 0.07* (0.03) 0.07 0.13* (0.05) 0.09 Parental SES Same Sex Pair (reference) Mixed Sex Pair Constant - - - - 1.78* (0.88) 0.07 0.43 (1.01) 0.01 6.43** (1.80) • 8.20** (2.30) • Observations (Pairs) Adjusted R2 837 0.045 906 0.059 **p<.01 * p<.05 + p<.10 (two-tailed) Robust standard errors in parentheses. 0.20 for the “fake” ones. In short, there was no reduction in the SES coefficient in the pseudo-sibling analysis; if anything, it looks like the pseudo-sibling simulation has made the SES effect more pronounced. As parental SES increases for the pseudo-siblings, their “sibling inequality” decreases; just as it did for the real siblings. What are the implications of this result? Clearly, in the simulation, parents could not have been doing any of the things proposed by the conventional wisdom because I switched out one sibling for a “fake” one from a different family, who only shares the same family SES level. Parents could not have assessed both children’s abilities and long-term prospects, since they only knew one child, nor could they decide how to invest across both children so as to alter the initial sibling differences, either reinforcing (if low SES) or minimizing (if high SES) differences, since they only actually invested in one of the two children. The parents could do nothing to affect the inequality of “fake” siblings, but the fact that the overall SES pattern is essentially the same illustrates that siblings from high SES parents must be more educationally equal based on socialstructural factors, beyond parental control. PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 195 Table 4 Coefficients of Variation of Educational Attainments for SES-Specific Populations and Among Siblings, by SES Low SES Families High SES Families Low SES CV ≠ High SES CV Overall Population Inequality Sibling Inequality 17.0 (n=925a) 21.8 (n=1046 a) ** 9.1 (n=386b) 11.8 (n=452 b) ** **p<.01 * p<.05 + p<.10 (two-tailed) a. Ns are for individuals. b. Ns are for sibling pairs. A more social-structural explanation for the relationship between parental SES and sibling inequality might be found if two conditions are met: (1) children of high SES parents fall into a tighter distribution of educational destinations, compared to children of low SES parents; and (2) sibling inequality mirrors the overall educational distribution of children from the same SES, such that a narrow educational distribution for high SES children translates into low educational inequality among high SES siblings, and vice versa for low SES children. Both of these conditions appear to be met. Condition 1 is met: as Table 4 indicates, educational inequality among all high SES children is much lower (CV=17.0) than among all low SES children (CV=21.8).5 Condition 2 is also met: as Table 4 shows, among high SES siblings, their sibling inequality is CV=9.1 vs. among low SES siblings, where their sibling inequality is CV=11.8. This data provides further support for a socialstructural interpretation of the relationship between parental SES and sibling inequality. CONCLUSION This paper advocated a stratification approach with a more relational perspective. I shifted from an absolute framework to a relative one, where educational inequality is modeled not between families, but within them. By shifting focus, this paper has documented a subtle mechanism by which SES operates to make children of high SES families in the United States more equal in their educational levels. While sibling educational inequality seemed like it might result from a random mixture of family interactions, it is actually affected by the overall socioeconomic system. As parental SES increased, the amount of sibling educational inequality 196 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY decreased noticeably as well. Even if many siblings do not experience this consciously as inequality, this difference in educations between siblings still matters because sociologists have also noted possible negative consequences of high sibling inequality, including the exacerbation of lifestyle differences, the limitation of information exchange and strained social relationships between siblings (Heflin & Pattillo 2006; Van Gaalen et al. 2008). This paper shows it is likely that certain very popular hypothesized mechanisms are not operative. The proposed mechanisms linked to parental preferences, investment strategies, and the like are found to not likely matter. These hypotheses are also tied to the narrow economics focus on “investment” and “class,” both of which are exclusively defined in terms of money. Actual mechanisms must be more structural and indirect in nature. Parental actions do not appear to be behind the SES patterns we observe. Parents clearly play a large role in their children’s educational similarity, but it is not the parents as agents of a given SES class, or responding to a given SES situation, that treat their children differently, but simply belonging to that SES class at all. Previous researchers rightly saw that high SES siblings have less educational inequality, but they attributed it to the wrong source. They looked for a micro-explanation involving parental investment behaviors, when the result appears to be really driven by the fact that high and low SES children – in general – have different educational destination distributions. Siblings within their own families merely reflect this general pattern in society at large. By finding that social-structural reasons are more consistent with the lower sibling educational inequality found among higher SES families, I highlight new possible mechanisms. On the one hand, this result could be caused by the sibling-blindness of many upward mobility public policies directed to low SES children. Upward mobility might emerge because policies only provide opportunity for a limited number of low SES children to move up, and not all the siblings from the same family have access to this limited number of slots or opportunities. On the other hand, a threshold model (where families invest to prevent children from falling below their own SES position) would produce the very pattern seen – small distance for high SES children, and larger distance for lower SES children; as long as the floor and ceiling range is narrower at the top of the SES distribution than at the bottom of it, which it is. Researchers PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 197 need to examine sibling inequalities in more detail and in a new light to confirm which forces are at work. From a stratification perspective, because inequality processes in general favor the powerful, the fact that high SES parents minimize sibling inequality suggests that sibling educational closeness is a real good. Sibling equality is a less obvious privilege, maximized by some classes more than others, and generally not noticed by anyone; this is reminiscent of how Schwartz (1974) showed that time (in very simple, everyday ways) can be monopolized by high SES individuals, since low SES people are asked to wait, while high SES people get to shortcut queues. Stratification researchers have looked to sibling correlations for an overall measure of the family of origin’s role in class reproduction. The sibling correlation of 0.5 has been interpreted to mean either: (A) “individual” factors like talent or luck still greatly impact educational success, since half of all academic variance is still within the same families (Conley 2004; Jencks 1979; Solon et al. 2000); or alternatively (B) familybased reproduction is still quite persistent, since siblings reach much more similar educational levels than their shared demographic (dis)advantages would predict (Bourdieu & Passeron 1990). While both of these interpretations are valid as far as they go, I have advanced this debate by providing additional evidence of cleavages in society that impact the family. Since greater uniformity is found among high SES families, this is another piece of evidence in favor of (B) that family-based reproduction still matters, and it is obscured when looking at a population-level parameter like the sibling correlation. Based on these analyses, the proverbial glass appears to be half-empty, not half-full, for low SES families because high SES families still manage to equalize more of their children’s educational futures. In this way, I extend the literature on family background and educational mobility (Hauser & Wong 1989; Hauser & Sewell 1989; Hauser & Mossel 1985; Solon et al. 2000). Trying to find a global measure of family background’s role on attainment must be tempered, therefore, by an awareness that there is often meaningful subgroup heterogeneity in how family background influences sibling variances in education. This paper’s main limitation is that it does not directly test the proposed mechanisms behind sibling inequality. Future research would benefit from looking at parental investment decisions directly, as well as parents’ prospective assessments and expectations of their children’s ultimate schooling levels.6 Also, researchers should look to how public 198 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY policies may exacerbate sibling inequality by not having an explicit preference for siblings of current participants in programs. A key extension of this paper would look for whether similar dynamics hold in other countries. We have some evidence that different countries have different sibling correlations on education and earnings (Sieben et al. 2001; Björklund et al. 2002; Sieben & De Graaf 2004). We could imagine high SES families have less ability to equalize their sibling educational attainments in countries where the educational system is tracked earlier or more entrance-exam-based; or where private family financing for higher education is less common than in America; or where family-life transitions are more equally distributed among classes. This would be fruitful to explore. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Tom DiPrete and Peter Bearman for valuable comments on preliminary versions of this paper. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2007 annual meeting of the Eastern Sociological Society in Philadelphia, where I benefited from Chuck Willie’s helpful feedback. Notes 1. The SAF staff then attempted to contact this sibling for additional questions; telephone interviews were conducted with 1,155 of those siblings (for more information, see Warren 2001); this additional information on this smaller sample is not used in this paper. 2. Where multiple families shared the same exact SES rank, I broke ties randomly. I kept the GSS-respondents in rand order, but shifted down their randomly-chosen siblings by one family. 3. Since the GSS does not provide exact birth dates, these ages are imprecise within (at most) 12 months. 4. Using the formula: 5. “High SES” and “low SES” refer to above and below mean parental SES, respectively. 6. Additional possible objections concern: (A) measurement error. Measurement error is not likely driving these results, since it is not thought to be especially high with regard to siblings. Hauser and Wong (1989) note that “proxy reports of status variables by adult offspring about one another are just about as accurate as are self-reports” (168). (B) Parental SES is affected by age of the parents. I ran models adding in maternal and paternal age, and PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 199 while those variables were significant, they do not alter my results appreciably (results available upon request). (C) Other measures of sibling inequality would produce different results. I run models with other measures of sibling inequality, like the absolute difference in educations. Results were equivalent (results available upon request). (D) The top-coding on educational attainment artificially induced lower overall educational inequality among high SES children, and siblings, but when I remove all the top-coded cases, the results are equivalent (results available upon request). References Abdulkadiroglu, A. and Pathak, P. A. and Roth, A. E. and Sonmez, T. (2005). The Boston Public School Match. American Economic Review, 95(2): 368371. Allison, P. D. (1978). Measures of Inequality. American Sociological Review, 43: 865-80. Argys, L. M., Daniel I. Rees, Susan L. Averett, and Benjaman Witoonchart (2006). Birth Order and Risky Adolescent Behavior. Economic Inquiry, 44(2): 215-233. Becker, G. S. (1981). A Treatise on the Family, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Becker, G. S. and Tomes, N. (1976). “Child Endowments and the Quantity and Quality of Children.” Journal of Political Economy: 143-162. ——(1986). Human Capital and the Rise and Fall of Families. Journal of Labor Economics, 4: S1-39. Behrman, J. R., Robert A. Pollak, and Paul Taubman (1995). From Parent to Child: Intrahousehold Allocations and Intergenerational Relations in the United States, Chicago: University of Chicago. Björklund, A., Tor Eriksson, Markus Jäntti, Oddbjörn Raaum, and Eva Österbacka (2002). Brother Correlations in Earnings in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden compared to the United States. Journal of Population Economics, 15(4): 757-772. Blake, J. (1989). Family Size and Achievement. Berkley: University of California Press. Blau, P., and Otis Dudley Duncan (1967). The American Occupational Structure, New York: Wiley. Bourdieu, P., and Jean Claude Passeron (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, New York: Sage Publications Inc. Breen, R. and Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). “Explaining Educational Differentials: Towards a Formal Rational Action Theory.” Rationality and Society 9(3): 275+. 200 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Blau, J. R., and Peter M. Blau (1982). The Cost of Inequality: Metropolitan Structure and Violent Crime. American Sociological Review, 47(1): 114-129. Chu, C. Y. Cyrus, and Ruey S. Tsay, and Ruoh-rong Yu. (2008). “Intergenerational Transmission of Sex-specific Differential Treatments: The Allocation of Education Resources among Siblings.” Social Science Research 37: 386-399. Conley, D. (1999). Being Black, Living in the Red: Race, Wealth, and Social Policy in America. Berkeley: University of California Press. —— (2004). For Siblings, Inequality Starts at Home. Chronicle of Higher Education, 50 (26) : B.6 —— (2004). Pecking Order: Which Siblings Succeed and Why. New York: Pantheon. Conley, D. and Rebecca Glauber. Forthcoming. “Sibling Similarity in Economic Status: Family Structure and Resource Effects.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. Dahan, M., Alejandro Gaviria (2003). Parental Actions and Sibling Inequality. Journal of Development Economics, 72(1): 281-297. Erikson, R., and Goldthorpe, John H. (2002). Intergenerational Inequality: A Sociological Perspective. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(3): 31-44. Freese, J., Brian Powell, and Lala Carr Steelman (1999). Rebel without a Cause or Effect: Birth Order and Social Attitudes. American Sociological Review, 64(2): 207-231. Gaviria, A. (2002). “Intergenerational Mobility, Sibling Inequality and Borrowing Constraints.” Economics of Education Review 21(4): 331-340. Goldthorpe, J. H. (1996). Class Analysis and the Reorientation of Class Theory: The Case of Persisting Differentials in Educational Attainment. The British Journal of Sociology, 47(3): 481-505. Hauser, Robert M. and Robert D. Mare (1994). Study of American Families, [computer file]. Madison, WI: Data and Program Library Service [distributor], 1997; <http://dpls.dacc.wisc.edu/Saf/index.html> Hauser, R. M., and William H. Sewell (1985). Birth Order and Educational Attainment in Full Sibships. American Educational Research Journal, 22(1): 1-23. Hauser, R. M., and Raymond Sin-Kwok Wong (1989). Sibling Resemblance and Intersibling Effects in Educational Attainment. Sociology of Education, 62(3): 149-171. Heflin, C. M., and Mary Pattillo (2006). Poverty in the Family: Race, Siblings, and Socioeconomic Heterogeneity. Social Science Research, 35(4): 804-822. PARENTAL SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS AND SIBLING EDUCATIONAL... 201 Hertwig, R., Jennifer Nerissa Davis, and Frank J. Sulloway (2002). Parental Investment: How an Equity Motive Can Produce Inequality. Psychological Bulletin, 128: 728-45. Hopcroft, R. L. (2005). Parental Status and Differential Investment in Sons and Daughters: Trivers-Willard Revisited. Social Forces, 83(3): 1111-1136. Hout, M. and DiPrete, T. A. (2006). What We have Learned: RC28’s Contributions to Knowledge about Social Stratification. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 24(1): 1-20. Jencks, C. (1979). Who Gets Ahead? The Determinants of Economic Success in America. New York: Basic Books. Kim, Hisam (2005). “Parental Investment between Children with Different Abilities.” Working Paper University of Wisconsin-Madison, Economics. Available at: http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~mbrown/Kim.pdf Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race and Family Life. Berkley: University of California Press. Mare, Robert D. and Meichu D. Chen (1986). “Further Evidence on Sibship Size and Educational Stratification.” American Sociological Review, 51(3): 403-412. Mazumder, B., Sibling Similarities, Differences, and Economic Inequality. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Working Paper, 2004. No. 2004-13. Raftery, A. E. and Hout, M. (1993). Maximally Maintained Inequality: Expansion, Reform, and Opportunity in Irish Education, 1921-75. Sociology of Education 66(1): 41-62. Rona-Tas, A. and Gabay, N. (2007). “The Invisible Science of the Invisible Hand: The Public Presence of Economic Sociology in the USA.” Socio-Economic Review 5(2): pp. Scarr, S., and Susan Grajek (1982). Similarities and Differences Among Siblings, in Sibling Relationships: Their Nature and Significance across the Lifespan, M.E. Lamb, Brian Sutton-Smith, Editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York. Schwartz, B. (1974). Waiting, Exchange, and Power: The Distribution of Time in Social Systems. American Journal of Sociology, 79(4): 841-870. Sieben, I., Johannes Huinink, and Paul M. de Graaf (2001). Family Background and Sibling Resemblance in Educational Attainment. Trends in the Former FRG, the Former GDR, and the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 17: 401-430. Sieben, I., and Paul M de Graaf (2001). Testing The Modernization Hypothesis and the Socialist Ideology Hypothesis: A Comparative Sibling Analysis of Educational Attainment and Occupational Status. The British Journal of Sociology, 52(3): 441-467. 202 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOCIOLOGY OF THE FAMILY Shanahan, M. J. (2000). “Pathways to Adulthood in Changing Societies: Variability and Mechanisms in Life Course Perspective.” Annual Review of Sociology, 26: 667-692. Solon, G., Marianne Page, and Greg Duncan (2000). Correlations between Neighboring Children in Their Subsequent Educational Attainment. Review of Economics and Statistics, 82(3): 383-392. Sørensen, J. B. (2002). The Use and Misuse of the Coefficient of Variation in Organizational Demography Research. Sociological Methods Research, 30(4): 475-491. Steelman, L. C., and Brian Powell, Regina Werum, and Scott Carter (2002). Reconsidering the Effects of Sibling Configuration: Recent Advances and Challenges. Annual Review of Sociology, 28: 243-269. Van Gaalen, R. I. and Dykstra, P. A. and Flap, H. (2008). “Intergenerational Contact Beyond the Dyad: The Role of the Sibling Network.” European Journal of Ageing 5(1): 19-29. Warren, J. R. (2001). Changes with Age in the Process of Occupational Stratification. Social Science Research, 30(2): 264-288. Zelizer, V. A. (2005). The Purchase of Intimacy. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press.